At the end of the Second World War, the American army confiscated thousands of examples of Nazi art. Deemed unsuitable for public display, they were spirited away to the United States and kept in private. The reason, according to researcher Gregory Maertz, was that these paintings were of such high aesthetic value that they were likely to complicate the official view of Nazism as pure and simple evil.

Though many of these works of art were returned to Germany, their aesthetic power and humanity continue to trouble the authorities. Maertz reports that there are German museums who even today deny the existence of works he has seen in their holdings with his own eyes. For any notion of Nazi compassion, or good Nazi art, confounds our deepest sensibilities and assumptions.

In an episode of Inspector Morse called “The Twilight of the Gods” (1993), Morse confidently assures Sergeant Lewis that “What we are looking for here is the sort of person that slashes pictures, takes a hammer to Michelangelo’s statues and a flamethrower to books; someone who hates art and ideas so much that he wants to destroy them: a fascist.” For the opera-loving Inspector, then, it is axiomatic that fascism is a form of vandalism, a nihilistic assault on civilization itself which took its most infamous form in the terror regime led by Adolf Hitler.

In 1989 the film-maker Peter Adam had at least taken Nazi culture seriously enough to produce a two-hour documentary on Art in the Third Reich for the BBC’s prestigious cultural series Omnibus. Yet he too confirmed the stereotype of Nazi art when he warned his viewers that the paintings, sculptures, and buildings they were about to see were the expression of “a barbaric ideology”. “One can only look at the art of the Third Reich through the lens of Auschwitz,” he concluded.

So while the catalogue of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s 2006 exhibition on modernism, “Designing a New World” singled out the Volkswagen as an outstanding specimen of modernist engineering and aesthetic principles, it still betrayed considerable uncertainty about how such an “advanced” and rationally beautiful piece of technology could emanate from a regime based on barbarity and the flight from modernity into rural idylls and fantasies of Aryan supremacy. The tendency has been to highlight the kitsch and vulgarly nostalgic aspects of Nazi art – symbolised by Hitler’s own dreary oeuvre – and separate out and deny the fascist origins of those modernist masterpieces we cherish.

Given the crimes of the Nazis such a manoeuvre is tempting. Tempting, but historically tendentious. Fascist nationalisms like Nazism and Mussolini’s Italian Fascism were never simply about a return to the past, and their sense of culture, of art and of human destiny has far more in common with other forms of 20th-century modernism – modernism that is perpetually fêted and in vogue – than most would like to admit. As Gregory Maertz has written, “mainstream Modernism has been sealed off from ideological and aesthetic contamination by the Third Reich.”

Unlike “modernity”, the impact of new technology and social relations which has the tendency to destabilise traditional societies, “modernism” is a term usually applied to the arts that have broken with the formal conventions of the Renaissance. However, a number of historians extend its remit further. They see the tide of aesthetic innovation that flooded European society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, bringing with it a tide of new “isms”, as symptomatic of a deeper impulse, namely the drive to formulate a new social order capable of redeeming humanity from the growing chaos and crisis resulting from modernity’s devastation of traditional securities.

Seen in this way a major paradox lies at the heart of modernism: its emotional wellspring is not modern. Rather it lies in a primordial human drive to erect what sociologist Peter Berger called “a sacred canopy” to act as a shield against the terror of the void of chaos and death. Modernity, by tearing holes in that canopy, by threatening the cohesion of traditional culture and its capacity to absorb change, triggers an instinctive self-defensive reflex to repair it by reasserting “eternal” values and truths that transcend the ephemerality of individual existence. If the canopy is damaged beyond repair the conditions are created for what is known to anthropologists as a “revitalisation movement” that seeks to erect an entire new canopy, a new metaphysical sky to make the world anew.

From this perspective modernism is a radical reaction against modernity. At its most programmatic and utopian, it is a bid to stem the tide of “decadence” by constructing an alternative modernity on the other side of contemporary society’s structural and moral self-destruction. It is against this background that racist variants of nationalism emerged. These sought to revitalise a decaying society by reconnecting modern citizens with their history, their culture, their ethnic roots and the soil, not in an anti-modern spirit but in order to establish a new future.

This perspective, then, invites a fresh way of understanding historically rather than mythically the sustained attempts by the Fascists, Nazis, Bolsheviks and Chinese Communists to socially engineer a modern, post-traditional and post-liberal society inhabited by a “New Man”. As modern versions of primordial revitalisation movements, they aspired to create a new type of totalitarian state, a “modernist state” whose policies were formulated within an overarching vision of history which provided a new canopy of transcendental values. They each attempted to make time anew. One obvious difference between them, however, was that whereas communism wanted to burn its bridges with the decadent feudal and capitalist past, Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany sought to mobilise the masses with mythic narratives of the cultural and racial superiority of ancient Romans and Aryans.

The fact that neither regime set about the destruction of capitalism and both instituted cults based on mythic heroic values has fostered the widespread assumption that fascism is an essentially anti-modern, reactionary, backward-facing political force, the parody of a “real revolution”. In fact Graeco-Roman and German mythological history for the Third Reich and the New Rome has the same function as the “primitive” to artists such as Stravinsky, Picasso, and Gauguin: they are conscripted into the founding of a better modern future.

So the ground-breaking technology of the “People’s Car” (originally the “Strength-through-Joy Car”) designed to run on the “Adolf Hitler Roads” of a national motorway system conceived with breathtakingly modernist élan is entirely compatible with Himmler’s bizarre “Ancestral Heritage” project to document the lost wonders of ancient Aryan civilisation. It should no longer be surprising that the same Goebbels who oversaw the purge of degenerate art in Germany should also make sure that Edvard Munch – the Norwegian painter responsible for the quintessentially modernist painting “The Scream” – be given a state funeral, his coffin flanked by Swastika banners.

Similarly, Albert Speer’s titanic building projects signalled not anti-modern nostalgia for the glories of Greek civilisation, but rather the rebirth of the Aryan will to construct in a style both timeless and ultramodern. In fact the “clean” lines of the stripped neoclassicism of civic buildings had connotations of social hygiene, just as the nude paintings and statues that adorned them implicitly celebrated the physical health of a national community conceived not only in racial but in eugenic terms.

Even the euthanasia campaign and the multiple genocides carried out by the Third Reich need to be understood not merely as orgies of wanton sadism and hate-inspired nihilism, not as a simple and totally alien inhumanity, but – a surely more chilling proposition – as the collateral damage of the struggle to bring about an anthropological revolution for the ultimate good of all humanity. Hitler’s most fervent converts hung on every word when he announced that “The new age of today is at work on a new human type. Men and women are to be healthier, stronger: there is a new feeling of life, a new joy in life.”

The ultimate Nazi goal was not only to increase excellence in all spheres of social existence, but to breed a superior type of human being. The Nazi activist Franz Pfeffer von Salomon formulated the logical implications of this qualitative vision of human worth for “inferior” life-forms with unnerving lucidity: “Trees which do not bear fruit should be cut down and thrown into the fire.”

What the Nazi world-view shared with humanism was a belief in the perfectibility of mankind, albeit that their racially pure, culturally homogeneous utopia entailed the purging of all dysgenic and decadent elements. Theirs was a selective humanism, a definitively modernist bid to apply biopolitical principles that graded individuals according to their degree of innate humanity. Thus, though it is discomforting, we should not be surprised to find that among their own kind Nazis and Italian Fascists could continue to show tenderness or compassion, any more than we should find it shocking that ancient Romans, slave-owners in the Southern states of the US or White South Africans in the days of apartheid cultivated their own variant of human empathy.

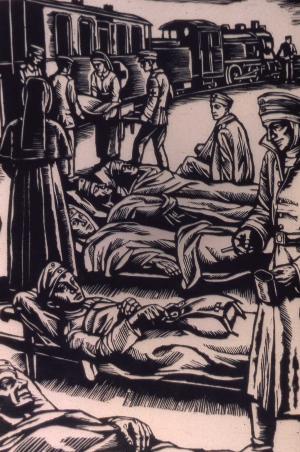

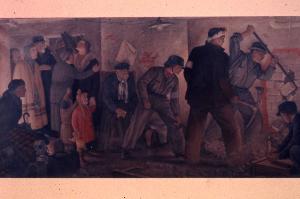

Nor is it inconsistent that powerful and compassionate art was produced under the Nazis. The human misery attendant upon the Allies’ terror bombing of major cities, for example, was rendered in telling detail by Adolf Wegener, an official Wehrmacht combat artist and loyal Nazi. Some, like Hans Rossmanit, another German military artist, even found it within them to extend their humanist empathy – at least on canvas – to embrace Slav victims of the Barbarossa campaign, despite their official subhuman status.

While it is manifestly true that the Nazis wilfully destroyed works of art and human lives on an unprecedented scale, this was not a mere orgy of nihilism. It was a calculated act of “creative destruction”, of destroying to build. It did not “slash” paintings, but publicly ridiculed and on one occasion burnt modern paintings – though more often sold them off or placed them in the private collections of Nazi leaders – if they saw their subject matter or formal qualities as degenerate. Nazism thus attacked “cultural Bolshevism” as part of the same crusade that led it to “eradicate” what it saw as the products of dysgenic breeding, namely to make way for a new, healthy, revitalised German culture that would save the West from self-destruction.

Fascism did have a sense of culture, shared much with modernism and, incongruous as this is, produced works of humanity and human dignity.

The artworks shown in this article are taken from a batch of thousands confiscated by the US Army in 1946. Repatriated to Germany in 1986, they are housed in the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin. Their copyright is still unclarified. Courtesy Gregory Maertz.