Hogarthian is an adjective which William Hogarth, ruthlessly ambitious and with a highly self-conscious awareness of how he personally encapsulated all the English virtues, would doubtless have been delighted to bequeath to the English language.

It’s an interesting adjective too. In his book The Fatal Shore, describing the city from which the first white Australians were transported, Robert Hughes summed it up rather well: “Modern squalor is squalid yet Georgian squalor is ‘Hogarthian’, an art form in itself.” Without quite knowing why, we all recognise what it implies: an earthy, vicious yet also rather jolly rumbustiousness, neatly summing up all we think we understand by the 18th century. For instance, we instantly recognise the difference between what is meant by “Hogarthian” and “Dickensian” London. The latter is filthy, crime-ridden, sentimental, pitiful but also, once we’ve recognised its hideous nature, reformable and consequently redeemable; the former, on the other hand, while being filthy and crime-ridden and occasionally sentimental, is depicted without pity, without hope of redemption, and is therefore, in its cynical slapstick, much, much funnier. That this isn’t quite what Hogarth intended is very much beside the point.

That said, Hogarth himself was familiar with the squalor. He was born and raised in Clerkenwell (where one of his father’s many failed enterprises was a coffee house where the patrons were only allowed to converse in Latin). He lived close by the Fleet Ditch, the open sewer flowing from Smithfield, then still a livestock market where they did the butchering in situ, down towards the Thames where Blackfriars Bridge now stands. Its stinking course acted as a kind of natural barrier between the printers and lawyers to the west and the merchants in the City, and also endures as a metaphor for “Hogarthian” London (until it was covered by Farringdon Road in the 19th century), well before Hogarth started to depict the city. This is Jonathan Swift in “A Description of a City Shower”:

That said, Hogarth himself was familiar with the squalor. He was born and raised in Clerkenwell (where one of his father’s many failed enterprises was a coffee house where the patrons were only allowed to converse in Latin). He lived close by the Fleet Ditch, the open sewer flowing from Smithfield, then still a livestock market where they did the butchering in situ, down towards the Thames where Blackfriars Bridge now stands. Its stinking course acted as a kind of natural barrier between the printers and lawyers to the west and the merchants in the City, and also endures as a metaphor for “Hogarthian” London (until it was covered by Farringdon Road in the 19th century), well before Hogarth started to depict the city. This is Jonathan Swift in “A Description of a City Shower”:

“Sweepings from butchers stalls,

dung, guts and blood,

Drowned puppies, stinking sprats,

all drenched in mud,

Dead cats and turnip-tops come tumbling down the flood.”

Again, as with so much of Hogarth’s dark art, mixed in with the squalor there’s something intrinsically if indefinably funny about those lines.

Sadly, Swift and Hogarth never worked together in a kind of 18th century pre-echo of Hunter S Thompson and Ralph Steadman, but the connection between the two is obvious. They were both central to the blossoming of satire in the half century after the Glorious Revolution and both had no compunction in describing, visually or verbally, all the shit and piss and blood endlessly flowing in the gutters alongside the Enlightenment, as well as the venality, stupidity and vanity strutting through and around them.

The great 20th-century political cartoonist Sir David Low described Hogarth as “the grandfather of the political cartoon”. What Low meant was that Hogarth possessed all the tools without quite creating the final template for what we now recognise as a political cartoon (that was left to James Gillray 40 years later). Even so, everything else was there: the use of images for didactic as well as satirical purposes, the utilisation of humour in a visual way to press the point home and the mass production of those images so that they could do their polemical work among as many people as possible. Given the attitudes of the Enlightenment – a distrust of both humour and the visual – those achievements should have kept him firmly in the gutter; but Hogarth not only enriched the gutter (and himself) but also elevated its sweepings into something perilously close to Art, while simultaneously becoming one of England’s greatest “conventional” artists.

Initially his fame rested on his engravings. The Harlot’s Progress was an instant bestseller (and remember that these images were sold as individual artifacts from print shops, or frequently borrowed overnight, like a modern video or DVD). It was followed by A Rake’s Progress, Marriage a la Mode, Industry and Idleness, Four Stages of Cruelty as well as Gin Lane, possibly the most famous image of his time and, again, largely responsible for how we think we understand those times. These prints – the way they were produced, the reason for their production and the way they were distributed – have far more in common with what we’d now call journalism than with art. And yet Hogarth was also, through his own endeavours, an artist. He wrote art criticism, created what he considered a new and specifically English school of art, and ended his days as Serjeant Painter to the King. Earlier, as an example of his ambition, he’d married the daughter of the then Serjeant Painter, Sir James Thornhill; proof of his ruthlessness lies in the fact that he initially eloped with her. Along the way he captured every market available: the series of engravings, widely available, would invariably be followed by painted versions of the same, so he could bestride the streets and the salons. To protect his interests in the former, he was largely responsible for the first Copyright Act being passed by Parliament.

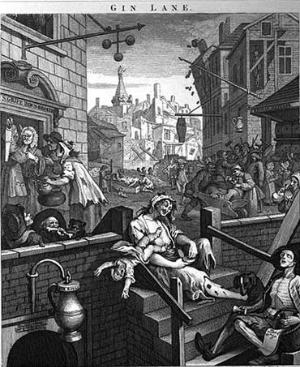

And yet Hogarth’s fame – his “Hogarthianness” – almost certainly rests on his prints, specifically on the ones that remained just prints and didn’t undergo the transubstantiation into respectability through oil paint. But exactly how “Hogarthian” was Hogarth? Let’s look at Gin Lane.

And yet Hogarth’s fame – his “Hogarthianness” – almost certainly rests on his prints, specifically on the ones that remained just prints and didn’t undergo the transubstantiation into respectability through oil paint. But exactly how “Hogarthian” was Hogarth? Let’s look at Gin Lane.

As an artifact it exists purely in the realm of the proto-mass media; it’s journalism, in as much as its original existence, as a plate prepared for printing, is not public; we only know it in its final condition as something reproduced. This is important. It’s also important that it was one of Hogarth’s cheaper series, printed on poor quality paper to ensure that it underwent as wide a circulation as possible. That was because its purpose was entirely polemical.

If you deconstruct the image down to its basics, Gin Lane is exactly like a modern tabloid headline, about some crack addicts murdering an old lady for her pension money. Hogarth was inspired to produce it by a news story about a woman who murdered her baby daughter in order to sell her clothes so she could buy gin. Gin – “genever” – was the curse of the urban poor, cheap and ubiquitous; it was, moreover, foreign, and led to the kind of temporary madness whose more permanent counterpart Hogarth had already depicted in the final print, set in Bedlam, of A Rake’s Progress.

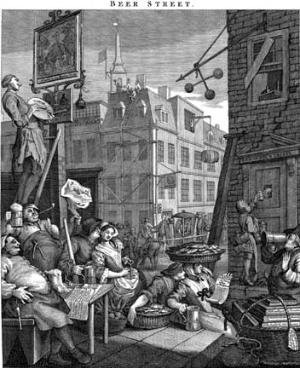

And yet Beer Street is dull; it’s Gin Lane that infects and lives on in the mind, and this is because it’s funny. True, it’s a very dark and bitter type of humour, but that’s usually the best kind: from the pissed-up Madonna dropping her baby to its certain death, to the scenes of suicide, degradation, impaling, disinterment of corpses, drunks fighting with dogs over bones, all these elements make us laugh, albeit guiltily and against all our best instincts.

And Hogarth pulls this trick of dragging humour out of horror over and over again. In Industry and Idleness, another series of cheap prints intended to be hung up in the workshops of the City, where presumably young apprentices would get the message, there’s a scene depicting the Industrious Apprentice presiding at the Lord Mayor’s Banquet.

Hogarth’s point is that if you work hard you’ll end up as Lord Mayor, but the figure of the Industrious Apprentice is tiny, stuck in the background, because Hogarth can’t help himself from making the focal point of the image a bench full of fat, sweating burghers at trough, themselves previously industrious apprentices enjoying the rewards of their virtue. And the depiction of the fate of the Idle Apprentice, who gambles and whores and murders his way to the gibbet at Tyburn, doesn’t quite work in the way Hogarth probably intended: the gallows are central, but too far in the background, and the eye is distracted by all the tiny details of the crowd in a scene which is almost carnivalesque, and unquestionably jolly.

To put it bluntly, and to link back to the squalor Hogarth saw beneath the finery, he just couldn’t stop himself from, almost literally, “taking the piss”. This may not have been the effect that Hogarth the polemical journalist wanted to achieve.

Sometimes, however, he took too much of it. In the last years of his life, by now firmly entrenched in the Establishment he’d relentlessly satirised and striven so hard to join, he published a caricature of his former friend, the radical journalist and politician John Wilkes, during his trial for seditious libel. The print shows Wilkes as a leering monster, his wig curling up into demonic horns, a “cap of liberty” looking more like a chamber pot atop a phallic staff. It’s a typical piece of satirical voodoo, calculated to do damage at a distance with a sharp object, namely an engraver’s tool. This time, the mixture of journalism and satire backfired on Hogarth, probably fatally: Wilkes’ supporters took the caricature as their own, Hogarth unwittingly providing them with the mass circulation image which they needed and reproduced over and over again. Worse, Wilkes loosed his chief attack dog, a former priest and poetaster called Charles Churchill, on Hogarth, described by Churchill at Wilkes’ trial thus:

Sometimes, however, he took too much of it. In the last years of his life, by now firmly entrenched in the Establishment he’d relentlessly satirised and striven so hard to join, he published a caricature of his former friend, the radical journalist and politician John Wilkes, during his trial for seditious libel. The print shows Wilkes as a leering monster, his wig curling up into demonic horns, a “cap of liberty” looking more like a chamber pot atop a phallic staff. It’s a typical piece of satirical voodoo, calculated to do damage at a distance with a sharp object, namely an engraver’s tool. This time, the mixture of journalism and satire backfired on Hogarth, probably fatally: Wilkes’ supporters took the caricature as their own, Hogarth unwittingly providing them with the mass circulation image which they needed and reproduced over and over again. Worse, Wilkes loosed his chief attack dog, a former priest and poetaster called Charles Churchill, on Hogarth, described by Churchill at Wilkes’ trial thus:

Virtue, with due contempt, saw

Hogarth stand

His poisonous pencil in his

palsied hand.

Hogarth riposted by burnishing out his own self-portrait and engraving a picture of Churchill as a drunken bear with Hogarth’s pug dog pissing on Churchill’s poems. And on they scrapped (between Churchill’s debilitating bouts of syphilis) until both men died, within weeks of each other. Hogarth’s final print, Finis – or, The Tail Piece – The Bathos, &c is a truly chilling picture of pitiless ruination, grotesquery, cracked palettes, hopelessness and final, utter despair.

Hogarth riposted by burnishing out his own self-portrait and engraving a picture of Churchill as a drunken bear with Hogarth’s pug dog pissing on Churchill’s poems. And on they scrapped (between Churchill’s debilitating bouts of syphilis) until both men died, within weeks of each other. Hogarth’s final print, Finis – or, The Tail Piece – The Bathos, &c is a truly chilling picture of pitiless ruination, grotesquery, cracked palettes, hopelessness and final, utter despair.

Personally, whether as journalist, artist or satirist, it was a horrible end. But it was also, unavoidably, unquestionably Hogarthian. ■