Until recently, universities have been slow to recognise the threat of radical Islamic activity on their campuses. They are understandably reluctant to curb the activities of students, especially as academics responded so vehemently to government suggestions that they should be actively policing their students. But it’s now no longer possible to ignore the fact that radical Islam is a growing force in our universities. For humanists, the dilemma is a troubling one. Should we follow our natural instinct to support the fundamental importance of free speech? Or is this a rare example of a situation that does justify censorship, because of the known links between some forms of Islamist propaganda and terrorism?

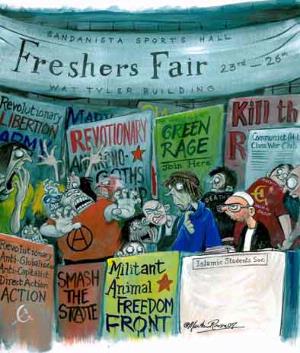

There is an historical precedent. Back in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s the growth of revolutionary socialism and libertarian anarchism on campuses across the country certainly seemed to threaten the liberal traditions of academia, particularly when the theoretical argument led to practical occupations and violent demonstrations, and even the declared intention to transform universities into “red bases” from which the revolution could be launched. It was a sufficient threat to lead several academics to demand an end to campus free speech and the dismissal and criminal prosecution of the principal student protagonists. And yet the threat passed. What once looked like a menace to civilisation is now little more than an historical paragraph or a mere footnote in the biographies of a few cabinet ministers.

There is an historical precedent. Back in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s the growth of revolutionary socialism and libertarian anarchism on campuses across the country certainly seemed to threaten the liberal traditions of academia, particularly when the theoretical argument led to practical occupations and violent demonstrations, and even the declared intention to transform universities into “red bases” from which the revolution could be launched. It was a sufficient threat to lead several academics to demand an end to campus free speech and the dismissal and criminal prosecution of the principal student protagonists. And yet the threat passed. What once looked like a menace to civilisation is now little more than an historical paragraph or a mere footnote in the biographies of a few cabinet ministers.

Radical Islam is certainly now exercising some contemporary academics. In 2005 Professor Anthony Glees caused a furore when he named more than 30 universities where “extremist and/or terror groups” had been detected. His report When Students Turn to Terror was dismissed by many in the academic and student community as inaccurate, anecdotal and alarmist. Indeed, a statement by the National Union of Students, issued in response to the report, read: “This paper offers nothing to the serious debate about how to address terrorism in society.” This reaction shocked Glees, who told me he “was surprised at the extent of hostility shown by Vice Chancellors to a very simple piece of dot-joining research.” Glees was similarly shocked by the academic union’s reaction to government guidelines which advised academics to monitor their students more closely and report any suspicions of extremism. Glees heartily approved of this strategy, but in May this year members of the University and College Union voted unanimously to reject such recommendations, insisting that they would “jeopardise trust and confidence between staff and students” and add to the climate of Islamophobia.

Does Glees have reason to be so agitated? Cases reaching our courts in recent months do suggest a clear link between student Islamism and terrorist offences. In July alone there were three such instances. Yassin Nassari, who was sentenced for smuggling terrorist training manuals into the UK, is said to have been radicalised while at the University of Westminster, where he was president of the Islamic Society in 2003. Omar Rehman, also of Westminster, was jailed for his role in a plot to attack a series of targets in the UK and USA, including the New York Stock Exchange and the London Underground. Elsewhere, four Bradford University students and a schoolboy were found guilty of possessing material for terrorist purposes, specifically internet propaganda designed to encourage martyrdom.

As a student at King’s College London in the mid-’90s, Derby-born Omar Sharif discovered political Islam and became a member of radical organisation Hizb ut-Tahrir, led at the time by Omar Bakri. Within the Hizb, Sharif would come to view world Islamic revolution and the establishment of a Caliphate as the only solution to the problems faced by the world’s Muslims, and in 1996 would follow Bakri into the now banned al-Muhajiroun. In 2003 Sharif travelled with fellow Briton Asif Mohammed Hanif to carry out a suicide bombing on a Tel Aviv nightclub. While Hanif’s bomb detonated, killing three and injuring 50, Sharif’s did not and he fled the scene. His body was found on a Tel Aviv beach two weeks later.

Yet there are approximately 90,000 Muslim students in the UK. Are these individual cases enough to constitute a genuine crisis, to justify calls for some modification of free speech on campus? Shortly after the publication of the Glees Report, Faisal Hanjra, a spokesperson for the Federation of Student Islamic Societies, dismissed his findings as unsubstantiated, stating: “There may be pockets of individuals who are operating on campus but they are not representative and they are insignificant.”

Two years on, Martin Everett, Vice Chancellor of the University of East London, agrees that Islamic extremism has not become widespread on campuses: “This has been grossly exaggerated. There is very little evidence that this is a general university-wide problem. Clearly as participation rates rise and more people enter higher education it is inevitable that some extremists will attend university. It is also true that students make new friends and so widen their own social networks whilst at university. So it is natural that they will be exposed to more extreme views, from both ends of the spectrum, but it does not follow that this is a problem. In fact I would argue that it is more likely to broaden their perspectives rather than create environments that allow extremism to develop.”

But can numbers turning to violent extremism, however small, ever be insignificant? Surely any number of students convicted of terrorism-related offences amounts to too many? The educational backgrounds of those involved in major attacks around the world suggest we are right to be concerned about the ideas floating around on campus. Analysing the backgrounds of 79 people involved in the 1993 World Trade Centre attack, the 1998 African embassy bombings, 9/11, the 2002 Bali bombs and the 2005 London attacks, Peter Bergen of think-tank the New America Foundation found that, of 63 whose education was known, two-thirds had been to university. June’s failed bombings in Glasgow and London, and the subsequent media hysteria over what the Mirror termed “Docs of War”, further highlighted the prevalence of educated men among would-be martyrs. Indeed, it later emerged that Glasgow Jeep passenger Dr Bilal Abdullah had been a particularly zealous member of Hizb ut-Tahrir during his time as a postgraduate student in Cambridge.

Those who find number counts unconvincing might be more exercised by the reports from insiders who claim to have evidence of the manner in which free speech is being manipulated by radical Islamists on campus. Ed Husain, author of The Islamist and a former member of Hizb ut-Tahrir, thinks the problem is urgent. Recounting his own experiences recruiting Muslim youth in London in the ‘90s, Husain emphasises just how fertile universities were as recruiting grounds for Islamist groups like Hizb ut-Tahrir. His conclusion is disturbing: “Home-grown British suicide bombers are a direct result of Hizb ut-Tahrir disseminating ides of jihad, martyrdom, confrontation and anti-Americanism, and nurturing a sense of separation among Britain’s Muslims.”

If any of this evidence is to be taken seriously, then how should universities be reacting? One response has been straightforwardly legalistic. Universities UK’s 2005 guidelines on extremism, “Promoting Good Campus Relations”, stated:

“The law protects the rights of staff and students to engage freely in the expression, development and debate of diverse ideas and view. . . However, Higher Educational Institutions should be prepared to take action if ideas or views infringe the rights of others, discriminate against them, or if any activity constitutes a criminal offence, [or] incites others to commit criminal acts.”

Groups like Hizb ut-Tahrir have responded in kind. They are careful to ensure they don’t step outside the boundaries of the law. They may advocate world Islamic revolution and the implementation of Shariah law, but they stop short of condoning suicide bombings on British soil.

Some universities have taken a more proactive path. Following the arrest of its Islamic Society president Waheed Zaman in August 2006 in connection with the plot to blow up transatlantic flights, London Metropolitan University appointed a moderate Imam, Sheikh Musa Admani, in an attempt to steer students away from extremism. At the University of East London, the Students Union Islamic Society works closely with the university authorities, providing a link between Muslim and non-Muslim students. To this end the society hosted an Islam Awareness Week in April this year which they say “provided opportunities for students and visitors to learn about the meaning of Islam and helped to break down stereotypes.” At the same time, the society says it maintains a strong stance against extremism, telling New Humanist: “We have never given a platform to extremist groups and individuals and work actively to ensure that extremist groups and individuals are identified and prevented from spreading ideas that are damaging to Islam and society.” Quite how the society goes about achieving this is unclear.

As a political ideology Islamism should be debated like any other but, as the testimonies of those who have emerged from the inside suggest, this is not something groups like the Hizb are really interested in. According to Ed Husain, far from looking to debate their ideas in the open, Hizb ut-Tahrir seek to infiltrate Muslim communities through the use of surreptitious front organisations. Speaking in July on the Today programme, Husain said he had come across the Hizb operating at his own university, London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), under the guise of the Open Mind Society. This is reinforced by a 2005 Sunday Times investigation which found that Hizb ut-Tahrir had been recruiting under the name Stop Islamophobia at universities across the London area. These groups are not looking to engage in intellectual debate with their opponents on campus, but rather to recruit Muslim students while they are young, impressionable and open to radical ideas. As another ex-member, Shiraz Maher, wrote in the New Statesman recently, it is dangerous for students to adopt these ideas because, while they may not espouse violence outright, they create “the moral imperatives to justify terror” and provide terrorists with “the support of an ideological infrastructure cheering them on”.

While student bodies may have played down concerns about extremism, individual students are not so sure. A postgraduate at Leeds told me she would feel uncomfortable if she knew extremists were operating on her campus: “I think free speech is vital and I would be worried that banning groups would just push them further underground. That said, I would feel threatened – and I would be concerned my lifestyle would be threatened – if there were radical groups hosting events on campus. I wouldn’t expect the university to allow the BNP to host talks on campus, and similarly I wouldn’t expect other extremist groups to be allowed to do the same.”

Another student I spoke to, an undergraduate at a university in London, took a different view. While acknowledging that the views of extremist groups are often threatening and offensive, he did not feel that censorship was the answer: “Banning them makes them more dangerous, allowing them to gain credibility and driving them further towards militant action. We have to remember that these people are no threat to our society. Their hate-filled ideology is entirely unpalatable to the majority of people in our country, including the majority of Muslims.”

For Anthony Glees, the answer to this problem is clear. He was astounded by May’s University and College Union ballot and shocked further when the Vice Chancellors’ union Universities UK gave it its full support, a decision Glees described as “bizarre, irrational and inexplicable”. Two years on from his initial report, he believes that “there is so much evidence of extremism on campus that I think the attitude of universities does need to be looked at by the government.”

Asked what should be done, Glees is uncompromising: “Universities should prevent groups using the safe space of academia to convert people to extremism. Groups like Hizb ut-Tahrir should be banned from campuses, and in my opinion banned from public life. I believe there is sufficient evidence for this. They call for a system of government opposed to our liberal, democratic system of government. We have to learn lessons from the history of the 20th century. Where democracies allow groups to use their weapons of democracy to subvert it, they get overthrown.”

These sentiments were echoed by historian Geoffrey Alderman, who has held senior administrative posts at the University of London and Middlesex University. “As a patron of the UK Council for Academic Freedom I view academic freedom as absolutely paramount, but feel we must draw the line at incitement to violence. Some universities should be more robust in ensuring the student learning experience is not overshadowed by fear and terror, even if that means banning certain groups from campus.”

Most controversial has been the recommendation that university lecturers monitor their students and report suspicious behaviour, but Anthony Glees disagrees that this is tantamount to spying: “Academics shouldn’t ‘spy’, that’s a job for the security services. But academics have always been paid to monitor their students’ activities. The idea that they’re not is absurd. Academics should engage with their students and, like anyone else in society, if they come across suspicious activity, for example incitement, they need to speak to the police about it. In saying they shouldn’t do this, academics are currently claiming a right no other professional has, not even doctors or lawyers.”

Martin Everett disagrees. While recognising the duty of citizens to report suspicious behaviour, he maintains that the government guidelines encourage spying: “I cannot support the idea that staff should in some way act as informers or spies. Students are here to gain an education and part of that education is to promote free speech and encourage debate. Staff must be seen as the catalyst that helps move students’ thinking on. Anything that compromises that role undermines the primary goal of higher education and I think what the government has proposed would do precisely that.”

Everett’s view reflects a wider consensus among academics. Few would deny that they are obliged to report illegal activity, but they felt the government was asking them to go further and actively monitor their students, in particular those from Muslim backgrounds. Academics have a duty of pastoral care towards their students and most universities have a personal tutor system in place to provide this. Tutors will monitor their students’ progress and intervene if it appears their studies are suffering, but the majority do not feel it is within their remit to interfere with their personal views. The feeling among members of the academic union was that monitoring students on behalf of the authorities would directly conflict with their duty of care.

Beyond the talk of banning groups, or promoting moderate views, or debating with Islamists, perhaps the most important contribution universities can make to tackling extremism is simply to continue doing their jobs. The experiences of both Ed Husain and Shiraz Maher actually contradict the idea of universities as a breeding ground for extremists. As Husain reveals in The Islamist, he was radicalised in his pre-university days and was at his most active when in charge of the Islamic Society at Tower Hamlets College in East London. Rather than strengthening his extremism, Husain’s time as an undergraduate actually facilitated his intellectual alienation from Islamist ideology. Through his studies in history, Husain realised that, despite their claims to be influenced purely by Islam, Islamist thinkers such as Syed Qutb and Taqiuddin al-Nabhani had been inspired by a whole host of Western philosophers and ideologues – Plato, Rousseau, Marx, Gramsci. With this realisation, Husain’s attraction to Islamism began to come crashing down.

Similarly, university study caused Shiraz Maher to question the tenets of Islamism. Researching the development of Islamic political thought in late colonial India for his Cambridge doctorate, Maher found, as he wrote recently in The Times, “marked points of rupture in both the historical and theological narrative of what the Hizb was having me believe”. Maher’s findings left him feeling lonely and confused, but his drift away from the ideas of Hizb ut-Tahrir had begun.

Their studies in the humanities helped both Ed Husain and Shiraz Maher to realise they had been wrong to adopt the ideology of Islamism. Universities exist to promote rigorous intellectual enquiry and the free exchange of ideas, and it is possible that by continuing to do just this they can do more to counter the activity of Islamist groups than could be achieved by any amount of bans, denial of platforms or monitoring of students. We must be careful not to hysterically overreact in the face of a handful of court cases and first-hand accounts. Perhaps the only stance universities can adopt is a legalistic one, a stance that has always been applied to student radicals. When activism spills over into incitement, it can be met with the full force of the law.