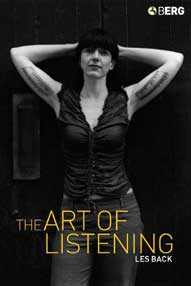

The book’s objects of enquiry are drawn from London life, covering such diverse phenomena as the unfairness of our immigration system, the official response to terrorism, and the role of tattooing in recent culture. In keeping with his desire to connect sociology to everyday life, each case study homes in on individuals, with Back insisting that we listen not just to what they are saying but to what they are unable to say. Tattooing becomes a way of declaring one’s identity and affinities in this respect: affinities that many in the working class find difficult to express otherwise. Thus Back’s brother has “Dad” tattooed on his shoulder in the aftermath of their father’s death: an ambiguous tribute since his father disliked tattoos. And in a genuinely tear-jerking moment, the woman on the book’s cover, Donna, has part of the musical score of Stevie Wonder’s song “Isn’t She Lovely” tattooed on her inside arms in memory of a goddaughter who died of brain cancer; the arms she held her in during the family’s final hospital vigil. At such points, Back delivers on his promise to develop a “live sociology”.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the book is the author’s dialogue with his own background. He quotes Marshall Berman: “I think it is an occupational hazard for intellectuals, regardless of their politics, to lose touch with the stuff and flow of everyday life. But this is a special problem for intellectuals on the left.” It is even more of a problem for intellectuals on the left like Back who hail from the working class. Aware of the frustrations of working-class existence, he no longer shares them, which cuts him off from his own family. Back resists the temptation to romanticise this background, but his insistence that all the subjects in his book, even those who are openly racist, be treated with respect shows where his loyalties lie. It can be difficult to be this generous faced with a white male racist, but, as Back notes, unless we engage with our enemies then we are not really practising sociology meaningfully. Sociology should be a source of hope for us: “We live in dark times but sociology – as a listening art – can provide resources to help us through them.” If anything can recover the somewhat tarnished reputation of sociology amongst the general public, then it is a book like this.

The Art of Listening is published by Berg