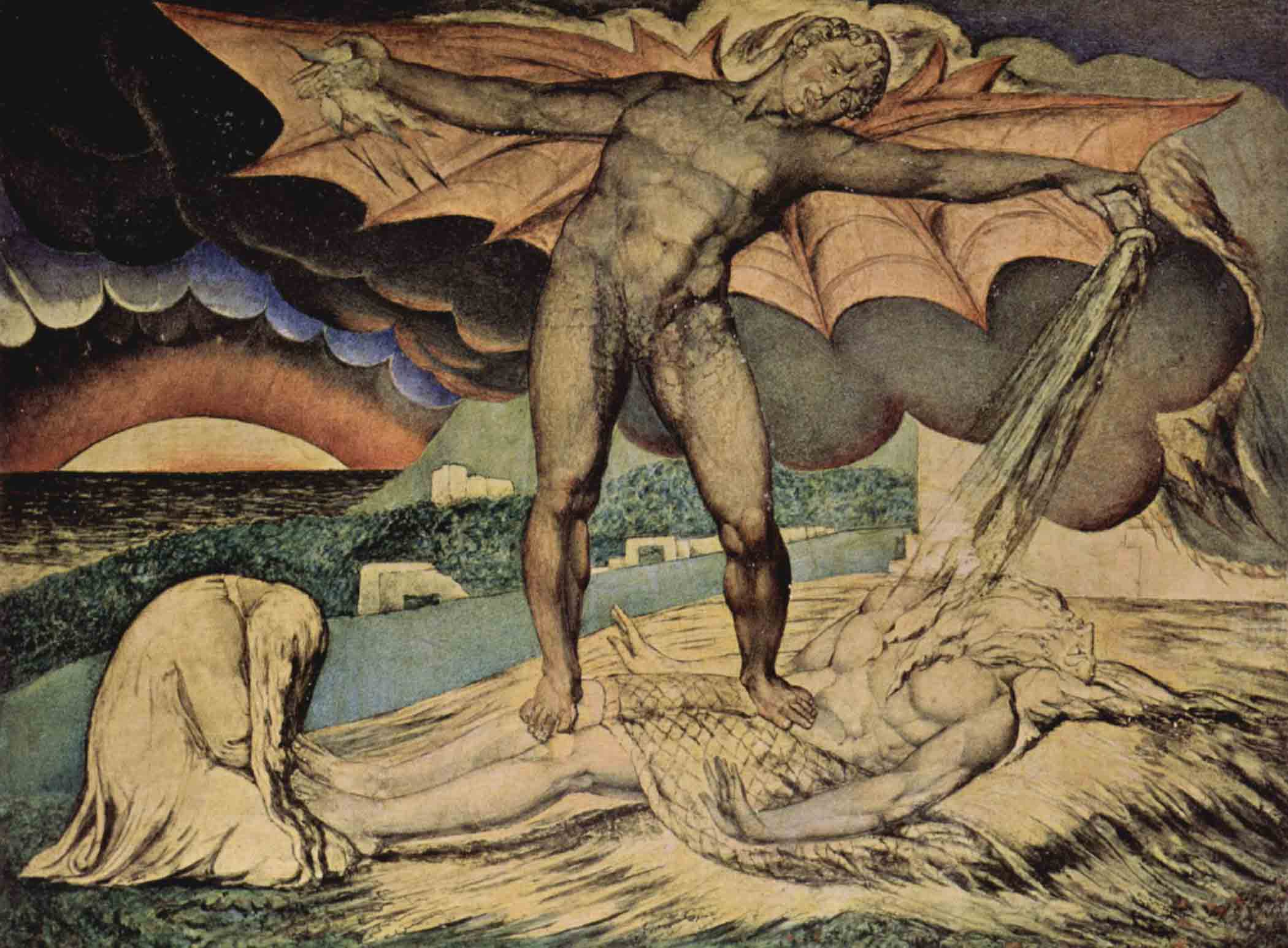

The last work Blake embarked on as an engraver was his stupendous rendering of The Book of Job and one of his last notebook poems, worked and re-worked, was “The Everlasting Gospel”. He didn’t do a Voltaire on his deathbed, but asked to be buried in the Dissenters Graveyard at Bunhill Fields, specifying that the service was to be Church of England. George Richmond, writing to Samuel Palmer to tell him of Blake’s death, reported that “He said that He was going to that Country he had all his life wished to see & expressed Himself Happy hoping for Salvation through Jesus Christ.”

We run into similar difficulties if we seek to claim Blake as a great Enlightenment thinker. He was simply a very confused thinker, albeit an incredibly imaginative one. When he proclaims in Jerusalem his desire to create his own system, he unintentionally puts his finger on the problem of engaging with Blake: he sure did create his own system but it is a system so arcane, so embroiled in its own solipsistic mythology, that it is a resounding failure. A magnificent failure, but a failure nonetheless, having no rational anchor in which to ground his creativity and no window that lets the reasoning light of society shine in on the dark and cavernous nooks and crannies of “The Emanation of the Giant Albion”.

However, it’s in Blake’s very attachment to, and belief in, the “human form divine” that the Lambeth engraver exhibits a humanism worthy of our attention, one that puts some of our more mealy-mouthed contemporary notions of what it is to be human to shame. In Milton, Blake – more than 200 years ago – damns the biological determinism that reduces humans to little more than the sum of fleshy DNA: “No Human Form but only a Fibrous Vegetation/ A Polypus of soft affections without Thought or Vision”. For Blake the “human form divine” is a very human imagination that transforms the world.

Throughout "Jerusalem" Blake’s clarion call is “the wonders Divine/ Of Human Imagination”, the very thing for building up Jerusalem, for creating a new society. Blake’s belief in the ability of the human imagination to make and create beyond the limits of the world as it is now is infectious and has inspired great art from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Surrealists, from Swinburne to Sinclair. Yet make no mistake. It is not just outré arty types that fall for the energy and creativity at the heart of Blake’s human vision.

The scientist and author of the still remarkable The Ascent of Man, Jacob Bronowski, loved Blake. In the book of the TV series the final plate is Blake’s frontispiece to Songs of Experience, accompanied by a note that concludes: “The personal commitment of a man to his skill, the intellectual commitment and the emotional equipment working together as one, has made the Ascent of Man.” In his book on Blake, A Man Without a Mask, Bronowski unwraps Blake’s vision in context and it is humanist to the core: “Blake’s thought rested squarely on the world in which he lived. The two revolutions which shook the world were actual in his life and are actual in his writings… Each society has given its own form: religious, literary, scientific. Much of the strength derives from the twofold form which dissent took in his time: rational and inspired.”