For months we have all known the result of the Russian presidential election. Dmitry Medvedev, Putin’s buddy from law school in Leningrad, will win a resounding victory, and promptly appoint his mentor and predecessor as Prime Minister. And so it has proved. The script was written, by Vladamir Putin of course, way back in December, when he issued the Delphic statement “I fully support this candidacy”, hours after Medvedev was nominated by United Russia (Putin’s party). And so the fresh-faced 42-year-old first deputy prime minister, chairman of the state gas monopoly Gazprom and former manager of Putin’s election campaign in 2000, found himself “elected” president three months before a single Russian voted for him.

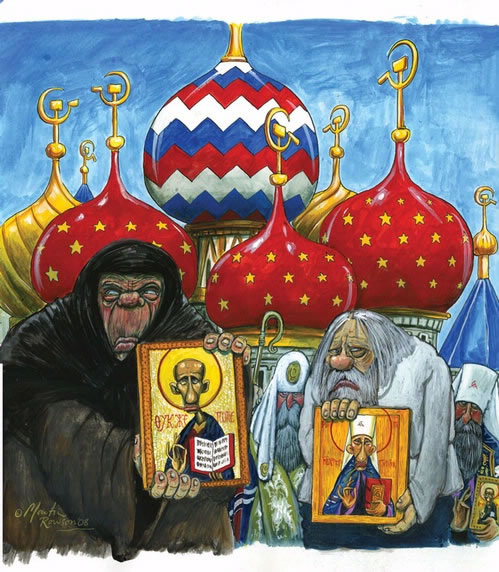

So Putin’s continuing influence is assured. And a significant part of his legacy is that religion is back in full swing. The KGB used to be in the vanguard of official atheism, but this is one legacy of his past life that Putin has repudiated. He is fervently and ostentatiously observant in his religious beliefs. As a result, the Russian Orthodox Church, now richer and more powerful than at any time for almost a century, has been at the centre of all state ceremonies, is a strong supporter of Putin’s policies and has resumed its traditional role as the spiritual arm of the Russian state. Restored churches can be seen everywhere. There are now some 28,000 parish churches in Russia, 732 monasteries and convents and thousands of priests training in seminaries. Putin delivers speeches at major religious festivals; in return the Patriarch acts as his agent in extending his control over all sectors of society. Church and Communist Party have become almost interchangeable.

So Putin’s continuing influence is assured. And a significant part of his legacy is that religion is back in full swing. The KGB used to be in the vanguard of official atheism, but this is one legacy of his past life that Putin has repudiated. He is fervently and ostentatiously observant in his religious beliefs. As a result, the Russian Orthodox Church, now richer and more powerful than at any time for almost a century, has been at the centre of all state ceremonies, is a strong supporter of Putin’s policies and has resumed its traditional role as the spiritual arm of the Russian state. Restored churches can be seen everywhere. There are now some 28,000 parish churches in Russia, 732 monasteries and convents and thousands of priests training in seminaries. Putin delivers speeches at major religious festivals; in return the Patriarch acts as his agent in extending his control over all sectors of society. Church and Communist Party have become almost interchangeable.

That’s one reason why most Russians are delighted. Putin is the most popular leader the country has known (the “huzzahs” for the Tsar were somewhat forced; those for Stalin decidedly more so). Even after eight years his popularity ratings are still an astonishing 80 per cent or so. While the stronghold of the church and the party are reassuring to Russians, the overriding explanation for Putin’s power is rather more worldly: money. Russians have never had it so good. Putin came to office just as the rising oil price began to make a real difference. The economy has grown by at least six per cent each year, and for the first time Russians have enough to splash out on foreign holidays, cars, consumer goods and Western imports.

The contrast with the Yeltsin and Gorbachev years is striking. Gorby may have wanted to reform communism, but he could not make it deliver: the shelves were bare, the choice pitiful and services sclerotic. Yeltsin’s era is remembered now as a time of anarchy (historically, the Russians’ greatest nightmare) when the law collapsed, miners, teachers and civil servants went unpaid for months on end and the oligarchs became obscenely rich by cheating the new privatised system.

As a result, Putin is associated with the good times. He has also been shrewd enough to exploit the delayed trauma of the Soviet Union’s collapse, appealing to the yearning for a “strong state”, for law and order, for Russia to be seen still as a great power and for a crackdown on dissent of all kinds – political, social or journalistic. But though he has brought back the old national anthem, restored some symbols, extolled Soviet patriotism and shown the world the sharp edge of Russian nationalism, he has not simply returned Russia to its communist past: he has gone far further back to tap into Russia’s tsarist history and, especially, beliefs. Absolute power goes hand in hand with absolute faith.

The Russian Orthodox Church has been able to reassert its power and authority so quickly after the collapse of communism because, despite ferocious persecution, it was never wholly crushed by the Soviet regime. Stalin all but eliminated religious observance until the Second World War when, realising the power of ancient belief, he mobilised the Church as part of Holy Russia’s war effort. Persecution eased, and was not resumed until Khrushchev, a fervent atheist, again sacked priests and closed churches.

Stalin had understood an important truth, however: the Church was still seen by many Russians as the embodiment of Russian culture and national feeling. Indeed, it still is – and under Brezhnev it became the main focus of a resurgent Russian nationalism. This was confined, naturally, to the Orthodox Church. Other denominations, especially the Baptists and the Catholics, were seen as foreign-oriented and therefore disloyal or subversive. They still are, and the Patriarch, who clearly has the ear of Putin, has ensured the passage of recent laws that bolster the Orthodox Church’s position at the expense of other denominations. Russian nationalism lay behind Moscow’s repeated rebuff of the last Pope’s requests to visit Russia. He was seen as the representative of a Polish-Catholic evangelism that was attempting to consolidate its gains in Ukraine at the expense of Orthodox influence.

The political influence of the Orthodox Church is hard to gauge. It is socially engaged – up to a point – in issues such as homelessness, charitable work and moral education, but remains intensely conservative. It takes a firm line against abortion and homosexuality (one reason why gay rights have never got anywhere in Russia) and would now frown on leftist opposition to the Putin government.

This conservatism is partly historical, but partly also because the Patriarch, Alexi II, finds himself in a precarious position. Being of Estonian origin, he has to prove himself doubly loyal to Russian national feeling. He also has to overcome the widespread view that, as a senior cleric during communist times, he was close to the KGB and may have acted at its behest.

The Church therefore now sees its role, as it did during the Brezhnev days, as the credible mouthpiece of the Kremlin abroad. It is influential in the World Council of Churches, it has forged good relations with the Anglican communion (though notably not with Rome) and it is working hard to unite the Russian diaspora in loyalty to Moscow. That has been eased by the recent official reunification of the Moscow Patriarchate with the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, created by exiles and White Russians who fled from the Bolsheviks in 1922, which formally broke off relations with the Moscow hierarchy in 1927.

Church attendance remains relatively low still. But neither Putin nor any Russian politician underestimates the nationalist appeal of the Church, even to the young. It chimes in with Putin’s policies and the current mood. As a result, a strong groundswell of opinion wanted Putin to run for a third term. He declined, because any change to the constitution would have looked too transparent and clearly self-serving. But his future role was much on his mind last September when he met a group of foreign correspondents. “Any future President will have to reckon with me,” he told us. “I intend still to play a role in my country.” Now we know what role: he hinted in the autumn that he was willing to stand as Prime Minister, a job that, until now, has been largely the chief co-ordinator of economic policy, clearly subservient to the President. That role may now be reversed.

How will Putin work in tandem with Medvedev? Clearly, he intends still to be the driving force. But already Medvedev is hinting that he wants to show a different face to the world – more pro-Western, more businesslike, less prickly and more “liberal” (the word must be qualified by the Russian context). Putin’s problem is that he cannot be absolutely sure that Medvedev will not begin to assert himself independently. Putin has built up a network of loyalties and obligations to ensure future control, and possibly run again for office in four years’ time. But there is nothing so fickle as loyalty in the Kremlin. The election may be a fix. But what comes after it is still a gamble.