It’s party time again. Once grand hotels are about to shrug off their fading gentility and rally in the September sun to the unmistakable twittering of conference babble. There’ll be all the staples: gruelling sessions at the bar; frantic late-night speech rewriting; high jinks in transgressive bedrooms; urgent breakfast meetings; covert mutterings and plottings; messages passed, mobiles vibrating. Punctuating the excitement and crush will be those vast, theatrical set pieces in the main hall, where reputations will be made or crushed.

It’s party time again. Once grand hotels are about to shrug off their fading gentility and rally in the September sun to the unmistakable twittering of conference babble. There’ll be all the staples: gruelling sessions at the bar; frantic late-night speech rewriting; high jinks in transgressive bedrooms; urgent breakfast meetings; covert mutterings and plottings; messages passed, mobiles vibrating. Punctuating the excitement and crush will be those vast, theatrical set pieces in the main hall, where reputations will be made or crushed.

And here amid the motions and amendments, the points of order and the standing items, the ovations and the slow hand claps, an insistent drone will be detectable: the sound of the new female political voice. For powerful women have been learning gradually that to be taken seriously they have to sound properly serious. No longer will Tory hearts quake at the gym-mistress squeakings of Ann Widdecombe, nor Labour stalwarts squirm at the self-effacing mumblings of Estelle Morris. Practically every woman in politics, now, affects more or less the same modulated, measured, alto tones of the normal, say-it-like-it-is speaking style.

No matter what the message, the sound must be one of reasoned care. Think of Caroline Flint suggesting that those feckless enough to be out of work should be evicted from their homes; Ruth Kelly opposing women’s right to abortion; Jacqui Smith proposing that stabbers be taken to hospitals to meet victims of knife crime. All of them come over as convincing, as if merely telling you the obvious, propounding the eminently sensible.

This new voice of reason resembles nothing so much as “sat nav” woman – that slightly nanny-knows-best intonation of the disembodied voice instructing you to turn right, then right again, sometimes directing you, confidently and reasonably, into treacherous marshland. The tone must be low and deep, the pacing slow, the pauses poignant. And no one was more conscious of the need to get it right than the country’s first female prime minister.

In The Human Voice Anne Karpf points out that Margaret Thatcher effected what was probably the most significant change in any modern politician’s voice. “Physically she had a problem in that she spoke from the top of her chest,” recalls Tim Bell, who masterminded the Conservative Party’s election-publicity campaigns. “Her voice would sound strangulated when she was tired and the voice would get tired sooner than anything else … When she first became leader of the opposition she had a schoolmarmish, very slightly bossy, slightly hectoring voice. It was a voice from the 1950s that was long gone.”

Thatcher’s publicity adviser Gordon Reece put it even more bluntly. Her high notes, he said, were “dangerous to passing sparrows”. According to Karpf, he was overheard “coaching her to say the words, ‘The socialists must learn that enough is enough.’ And trying to encourage her away from her more derided duchess tones.”

What Bell and Reece were attempting to expunge from Thatcher’s presentational style were those characteristics that have always been associated in the public mind with women’s voices. They are thought to be shrill and hysterical, or haughty and imperious. They screech like fishwives, laugh like drains, shriek like hyenas, nag like sirens, cackle like hens.

And there is some justification for the stereotype. When Bell spoke of Thatcher’s voice coming from the top of her chest he was identifying a basic difference between the way men and women tend to speak. Whereas men often breathe from their abdomen, women are more likely to constrict their voices to an upper range which allows less variety and less control. In a recent collection of essays, Well-Tuned Women, Kristin Linklater writes: “When a high voice connects with a strong impulse based, for instance, in anger or fear, it becomes shrill, strident, screechy, piercing, nasal, penetrating, sharp, squeaky or brassy and generally unpleasant to the point of causing major distress in the hearers.”

Men, on the other hand, with their deeper voices and richer tones, find it easier to convey authority and control. It’s partly physiological. Men’s voices are lower than women’s because they have a larger larynx, developed in the Adam’s apple at puberty, and longer, thicker vocal folds. And that’s what causes the breaking voice which has become one of the emblems of male puberty.

Yet these differences vary considerably across different cultures, races and communities. Deaf boys, for example, don’t experience the same dramatic deepening of the voice, presumably because they can’t hear the way men are expected to speak. So the marked contrasts in the West between the ways the two genders speak may well have as much to do with culture as with physiognomy.

Anne Karpf argues that men have come to assert power through their deep voices and resonant tones to such an extent that “pitch has become a weapon in the gender wars”. And religion, true to form, has capitalised.

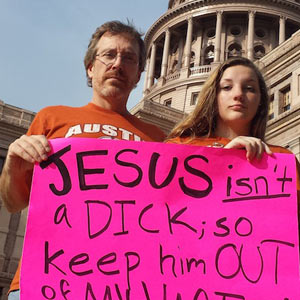

Women in the Judeo-Christian world were excluded from any form of sacred worship. The Old Testament prophet Samuel regarded the voices of women as indecent, which is why they were forbidden from reciting the holiest of Jewish prayers, the Shema. Jewish Talmudic law ruled that “men singing and women answering is promiscuity; women singing and men answering like fire set to chaff.”

St Paul decreed that women should remain silent in church. “For they are not permitted to speak but should be subordinate, as even the law says, if there is anything they desire to know, let them ask their husbands at home. For it is shameful for a woman to speak in church.”

Women’s voices were considered a temptation to lust because women themselves were unclean and bestial. But, paradoxically, the high, uncontaminated voice was at the same time extolled as being closest to God. In divine hierarchy, just as man is closer to the angels than woman, the head represents the spiritual and the lower half of the body is the physical. Church hymns, to this day, are usually set in higher keys than are comfortable for most of the congregation, so as to encourage the falsetto or head voice associated with heavenly choirs. The purest, most devotional chants and choruses within the Christian liturgy are the treble notes, unsullied by any hint of vibrato.

So how did the Church resolve the dilemma? Simple. It turned to boys, whose high, true warblings conveyed not just the ambrosial music of the heavens but a sexual purity, too. The castration of boys with the most beautiful voices not only ensured the continuation of their gifts but also of their virginity. So both the boy trebles and the powerfully high eunuchs produced the sounds of divinity – untried, untouched and sacred.

Not only were women disqualified from liturgical singing, they were also banned from sermonising. When they did begin to take a more public role they were often ridiculed as freaks. “A woman’s preaching,” remarked Dr Johnson, “is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.” Similar criticism, or worse, has routinely been hurled at the suffragettes, at women activists, trade unionists and campaigners.

So it’s hardly surprising that women have decided to relearn the techniques of strong public speaking. And where more logical to begin than by lowering the voice? Changing tone should at least begin to reverse the effects of those centuries of training when girls were encouraged to speak quietly and modestly, and to adopt sweet, high, ladylike voices in keeping with their inferior status.

Soft, sweet, girly voices are exaggerated by tight clothing that restrains upper chest breathing or unbalances posture. And, according to the voice coach Joan Mills, also writing in Well-Tuned Women, it was that apotheosis of restrictive clothing, the Victorian boned corset and ultra-tight lacing, which caused extreme hyperventilation and breathing difficulties for women. “The speaking voice which resulted would have been the breathy, thin, high and unresonant, rather childlike voices we associate with some of Dickens’ female characters, but which might have been considered a sweet, pleasing and feminine tone by many at the time.”

While a girlish voice denotes innocence and demureness, it can also signal a kind of sexy helplessness, especially when it carries a note of breathiness. This, Anne Karpf suggests, is because during orgasm the mucus in the larynx changes consistency and makes it vibrate less effectively. So the breathy, baby-doll voice perfected, albeit with a heavy dose of irony, by Marilyn Monroe manages to be both sexually inviting and tantalisingly virginal.

Light, high voices may be useful in the bedroom, but they are a bit of a drawback in the boardroom or the corridors of power. Dawn Primarolo, one of the very few women politicians who hasn’t deepened her voice, may be one of the most senior figures at the Treasury but the minute she opens her mouth you wonder if she can even be trusted with a piggy bank. Julie Burchill, high priestess of shock journalism and virulent opinions, undermines her strong writing with her silly upper-register whine, while Janet Street-Porter is widely ridiculed as “the human tannoy”.

So women try to deepen their voices to gain credibility and authority. Even Japanese women, who adopt an uncannily high pitch when in the presence of men to give an impression of powerlessness, will deliberately lower their vocal range at work to appear businesslike. Some are even undergoing surgery to make their voices more acceptable. When the television announcer Etsuko Komiya joined a serious news programme from a lighter daytime show, her male co-host urged her to deepen her voice, “to speak, not squeak”. It was felt that high female voices didn’t carry sufficient authority to speak to the nation. And this prejudice is not confined to Japan.

“A woman without bass registers in her voice,” Jon Snow once said, “would find it very hard to get on in broadcasting unless she was exceptionally beautiful.” And Anne Karpf points out that “the history of women’s exclusion from broadcasting represents perhaps the most blatant example of prejudice against women’s voices.” Women’s voices were thought to be monotonous, sharp, unpleasing and unsuitable for the microphone. In the early days of the BBC there were no women broadcasters at all, and although this gradually changed there was a very long established prejudice against female voices in certain areas of radio: sport, news and, most particularly, music.

In her essay “Justifying Injustice: Broadcasters’ accounts of inequality in radio”, Rosalind Gill analyses the discourse used by local radio controllers to explain why they won’t employ women as DJs. In her survey, conducted in the early 1990s, she encountered the familiar defences: women prefer to hear men; women don’t apply for this kind of work; their voices are too shrill; they don’t have the technical dexterity, the knowledge of music. But by far the most common excuse is that women simply don’t have the personality or the levity to be DJs. They’re too earnest and serious.

On the other hand, though, when Gill questioned them about the suitability of women for newsreading, the replies were reversed in a superb exposition of flexible sexism. Women, it seems, are too frivolous to convey the soberness of current affairs. “A newsreader needs to have reliability, consistency and authority,” explained Jim Black, then continuity editor at BBC Radio 4. “A woman may have one or two of these things but not all three. If a woman were to read the news, no one would take her seriously.”

Women’s voices now proliferate on air, but they sound very different from the early female broadcasters’. Over the past fifty years women’s voices have deepened significantly. Between 1945 and 1993 the average pitch of women aged 18 to 25 lowered by 23 hertz – equivalent to a semitone drop. Part of the change is a natural result of improved health and diet. And as women have grown larger their vocal cords have become longer, which means frequency or pitch is lower.

The deepening tones might also reflect the advances in women’s lives and opportunities. Their voices are beginning to match the assertiveness and confidence that women are achieving – as in so many other ways they are beginning to be more like men. But this can also be a gender trap. It’s a double- edged power. “The cultural rules women unconsciously obey are that their voices should be high and helpless or low and gentle,” writes Linklater. “If women’s voices are low and strong, they break balls.”

Men are both attracted to and repulsed by women with deep voices. A husky, slightly masculine voice can be sexy in the way that a woman in a man’s suit, or a girl in her boyfriend’s shirt, can be sexy. The male overtone serves to emphasise the woman beneath.

On the other hand, if a woman’s voice is too deep, too male, it can inspire both ridicule and fear. Indeed, in many cultures older women, whose voices deepen with the onset of menopause, used to be reviled as witches because it was thought they were turning back into men. So the deep-voiced woman can be so erotic she can turn men to jelly, or so croneish she can make them cower. The choice is between Mariella Frostrup and Dot Cotton.

In any case, according to the voice trainer Patsy Rodenburg in Well-Tuned Women, lowering the voice is merely a cosmetic tool, and doesn’t help to convey real power or authority. When she trained actresses to play male parts, “I began to realise the signals communicating maleness were connected to every physical aspect of power and a person’s relationship to power. This power is expressed throughout the body, breath, voice, speech and use of language. Every stage of communication expresses power or its denial.” She later began offering voice training to women in the workplace, dissuading them from simply deepening their voices, but instead concentrating on breathing, eye contact, physical confidence to produce a full, strong, sustained and focused voice, without hesitation or irritating repetition.

What she was doing was helping women to find their “true” or authentic voice – one which she felt had been eradicated by centuries of oppressive silencing. This “authentic voice” is defined by Kristin Linklater as one which conveys the full richness of womanhood – the “sound house” of the nursery, the kitchen, the bedroom, the garden, her place of work. It would be redolent with the sounds of crooning and storytelling, of mourning, keening, wailing, of singing at work and calling out her wares in crowded streets. It’s a voice capable of enormous strength and variety – a voice that can screech, laugh, nag, berate, gossip, weep, bellow.

This authentic voice, able to render joy and passion, suffering and anger, wild high ecstasy and deep, gurning despair, is the one that permeates the traditional singing of women from all over the world, from the Appalachians to Donegal, from the Balkans to Bali. As music began to become more refined, to enter the concert hall, the drawing room, and later the recording studio and the radio, the raw, harsh passion was diluted, the earthy female voice replaced by higher, sweeter tones, just as the speaking voice was.

Patsy Rodenburg found that the women who approached her for help either hated the sound of their own voices or else felt they were being mocked or put down at work if they expressed opinions too strongly. “I began passionately to believe that we are all born with a great voice, a clear, free and natural voice. This idea grew as simple voice work revealed wonderful voices overwhelmed by dire vocal problems.” But, she warns, if women simply imitate the speech habits of men then something innately female will be lost.

And that is what appears to have afflicted our current batch of women politicians. The weak and helpless voices may have disappeared, but so have many of the magnificent, utterly female ones: the fruity tones of Betty Boothroyd, the impishness of Edwina Currie, the indignant railings of Barbara Castle, the plain good sense of Gillian Shepherd. Instead, the new vocal style is one of monotone blandness at the expense of variety, richness or expressiveness. And even of meaning itself.

So if you want to get back in touch with your real voice, forget about sounding like the boys. What you need to do is to screech, to bellow, to guffaw, to cackle. Climb a mountain, halloo the reverberate hills, howl at the moon or ululate to the waves lapping on the shore. Shout, sister, shout out your passions and your griefs and your ecstasies.

And then, when you take to the stage or the boardroom or the microphone with your new-found womanly confidence, you’ll be ready to speak with truth and clarity and grace and power. Just as long as you actually have something worth saying.