When Francis Bacon died, he left an unfinished painting in the corner of his studio in Reece Mews, London. Around it were strewn pots and brushes and a mildewed mirror, books and photographs spilled out of every available nook, and lurid pink and blue paint greasily dotted the surfaces. The artist was frozen halfway through the act of creation – and this was seemingly a dirty and chaotic act. This incarnates the idea of Bacon as an iconic painter of tortured humanism, of bodies and sensation, and a life dominated by a dogged, dissolute pursuit of earthly pleasure.

When Francis Bacon died, he left an unfinished painting in the corner of his studio in Reece Mews, London. Around it were strewn pots and brushes and a mildewed mirror, books and photographs spilled out of every available nook, and lurid pink and blue paint greasily dotted the surfaces. The artist was frozen halfway through the act of creation – and this was seemingly a dirty and chaotic act. This incarnates the idea of Bacon as an iconic painter of tortured humanism, of bodies and sensation, and a life dominated by a dogged, dissolute pursuit of earthly pleasure.

The major new Bacon retrospective at the Tate Britain, opening this month, will mean many uses of that word “iconic”. The received idea of the iconic Francis Bacon – now the best-selling painter in the world at auctions, where his canvases sell for astronomical sums – is always tied up with lurid biography. Kiss-and-tell biographies and the biopic Love Is the Devil centre on spectacularly serious drinking in Soho dives, the painter’s complicated and eventually tragic love affairs with various bits of East End rough trade, with sex and death pervading it all. But perhaps Bacon’s painting is not so savage and raw as it might superficially seem – and maybe his is a colder, more distanced aesthetic than the received idea might imply.

This portrayal of Bacon as a tortured icon seems to take its cue from the painter’s own obsessive use of religious iconography. But for that, Bacon was always forthright about his militant atheism, and his use of Christian symbolism and imagery was always in a resolutely anti-spiritual context, reducing the crucifixion image of heroic suffering to flesh, meat, gore, cries of pain. The famous paintings of screaming popes, of men either wrestling or copulating, of physical extremity and 20th-century horror, fade into the iconic images of Bacon himself, from the famous photograph of him stripped to the waist holding up two sides of beef, to the images of the notorious studio.

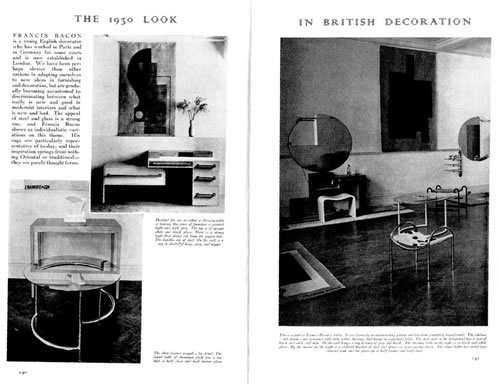

Yet the young Francis Bacon was a very different artist indeed, and his work represented a very different version of humanism. In 1930, the design magazine The Studio published an article entitled “The 1930 Look in British Decoration”, which included a photographic profile of the studio of a youthful Irish interior decorator. Bacon’s rooms were full of chrome and glass, neat cabinets, clean lines and a total lack of any clutter or mess. The rugs – produced to his own design – show discrete interlocking shapes and severe blocks of colour. Everything is spacious and ordered, almost surgical in its precision – something reinforced by the young designer’s use of hospital-issue rubber curtains. We’re a million miles from the famous Reece Mews studio, and a screaming Pope would look decidedly out of place.

Bacon stayed in Paris and Berlin in his late teens, and “the 1930 look” is under the very heavy influence of the aesthetics of both cities – what was called by critics the “new objectivity”. Ideologists of the movement like the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier were bent on the reordering of the world through design and architecture, through an industrial aesthetic of machine-made objects and serene rationality. The aim was to throw aside the detritus of history, religion and the accumulated weight of Western culture in favour of a supposedly scientific conception of hygiene and order, in which religion, cruelty and, seemingly, pain itself were effaced. If the later Bacon’s humanism was tragic, in 1930 it was a slightly derivative but advanced expression of a utopian, Modernist humanism.

Bacon stayed in Paris and Berlin in his late teens, and “the 1930 look” is under the very heavy influence of the aesthetics of both cities – what was called by critics the “new objectivity”. Ideologists of the movement like the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier were bent on the reordering of the world through design and architecture, through an industrial aesthetic of machine-made objects and serene rationality. The aim was to throw aside the detritus of history, religion and the accumulated weight of Western culture in favour of a supposedly scientific conception of hygiene and order, in which religion, cruelty and, seemingly, pain itself were effaced. If the later Bacon’s humanism was tragic, in 1930 it was a slightly derivative but advanced expression of a utopian, Modernist humanism.

But when he next came to prominence in 1944, the Bauhaus had long since been hounded out of Germany, and the idea of a future of ordered design and Apollonian rationalism had become highly ambiguous, as Europe eagerly returned to barbarism. Although Bacon would always disavow any historical or political meanings imputed to his work, his paintings of the mid-’40s, like the screaming, mutated subhuman figures in “Three Studies for Figures at the base of a Crucifixion”, were immediately taken as speaking to the realities of Auschwitz and Hiroshima.

In 1950, the photographer Sam Hunter visited Bacon’s studio in Cromwell Place, South Kensington. The photographs of “working documents” he took there are extensively documented in Martin Harrison’s book In Camera: Francis Bacon, where they appear almost as works of art in their own right – perverse photomontages of the media landscape of the 20th century, all of them ripped from illustrated books and newspapers. One of the most famous of the photographs shows, rammed together on card, images of Goebbels haranguing a crowd, a photograph of Baudelaire, Velazquez’s portrait of Pope Innocent X, crowds in Petrograd in 1917 fleeing from police gunfire, “Christ Carrying the Cross” by Grünewald, and glamorous images of film stars.

Practically all of this raw material finds its way into Bacon’s paintings, as Biblical suffering, the regimented hysteria of Fascism, images of power and of panic, are corralled together via a Baudelair-esque aesthete’s eye. For instance, the shouting demagogue morphs into the snarling faces of the ‘40s paintings, the film stars feed into an essentially aestheticised, sexualised approach to the human figure, and the cheap reproductions of Renaissance religious art are brutalised into Bacon’s own desacralised, carnal universe.

This world included everything that “The 1930 look in British Decoration” deliberately expunged or ignored. The atavistic and the carnal spilled out all over the place. The austerely rationalist, geometric art that accompanied the 1930 look, subsequently developing into op art and minimalism, would be dismissed by the mature Bacon as mere “pattern-making”. Yet the paintings took the rationalist, Modernist spaces used by the one-time interior designer and made them Gothic and irrational. In most of the famous works painted after Velazquez’s “Pope Innocent X”, the opulent throne and the velvet curtain are reduced to an indistinct space and a spare metallic frame.

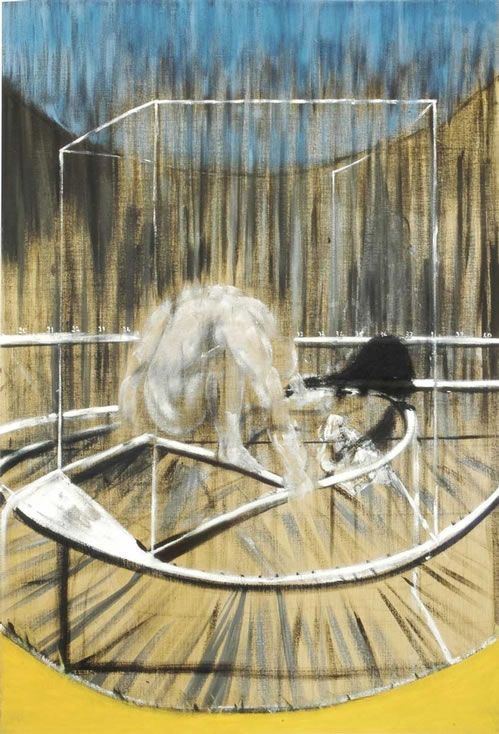

A typical example is in the 1952 painting “Study for Crouching Nude”. In the centre of the frame is a pallid and ghostly, yet taut and muscular naked male body, crouching in some sort of obscure act of exertion over what looks like a crumpled newspaper. Yet, look at the actual frame itself, and it’s clear that this is a wholly Modernist space. The metallic construction the figure is hanging on to is not unlike one of Bacon’s tubular steel and glass tables. While in photographs of the young Bacon’s interiors the rooms are either empty or languidly inhabited by neat aesthetes, here the space is filled with harsh physicality, and overwritten with grimy stripes of brownish paint as if to emphasise the seediness. But it’s a mistake to see this as mere vitalism, as a straightforward immersion in the carnal facts of flesh. That would be to ignore the very Modernist distance Bacon sets up between the represented body and the spectator. First, there’s the glass frame in the picture – and second, the glazing that encases the canvas. Bacon always specified that his paintings be shown under glass, not to stop them being damaged but to keep the viewer at arm’s length, and to increase the fascination of the untouchable object in the vitrine.

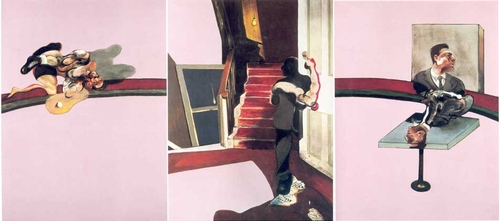

Almost all of the interior spaces in Bacon’s paintings are Modernist ones, places where rationalism goes awry, and where violent acts are played out inside an abstracted frame. One of the rare exceptions is the 1971 “Triptych in Memory of George Dyer”, painted in remembrance of the painter’s long-term lover, who had committed suicide in the same year. In the central panel, the glass cages are replaced by a Victorian staircase, in an almost representational space. In another panel, a bulging, melting figure writhes on a strip of board. It’s almost impossible to look at it without the weight of biography, mythology and the cant of the “iconic” obscuring it. Dyer was a petty criminal whom Bacon met when he tried to burgle his flat and who was caught up in Bacon’s alcoholic milieu. His death has always exemplified the human tragedy that supposedly drives all of these canvases.

Almost all of the interior spaces in Bacon’s paintings are Modernist ones, places where rationalism goes awry, and where violent acts are played out inside an abstracted frame. One of the rare exceptions is the 1971 “Triptych in Memory of George Dyer”, painted in remembrance of the painter’s long-term lover, who had committed suicide in the same year. In the central panel, the glass cages are replaced by a Victorian staircase, in an almost representational space. In another panel, a bulging, melting figure writhes on a strip of board. It’s almost impossible to look at it without the weight of biography, mythology and the cant of the “iconic” obscuring it. Dyer was a petty criminal whom Bacon met when he tried to burgle his flat and who was caught up in Bacon’s alcoholic milieu. His death has always exemplified the human tragedy that supposedly drives all of these canvases.

When we look at it, we might convince ourselves that we’re immersed in the brute realities of emotional and physical pain, and glean some kind of tragic humanist meaning from that. The painter thought otherwise. “I wasn’t trying to express the sorrow at someone committing suicide. I was not trying to express anything.” It remains aesthetic, objectified – perhaps as much as “The 1930 look in British Decoration”. All that shock and horror is mediated, held under glass. When the super-rich like Roman Abramovich pay out eight-figure sums for his paintings they know they aren’t throwing themselves into flayed flesh and raw meat but enjoying a coldly beautiful object. In a sense, this is what Bacon was doing all along.