Think of the Renaissance. Feel the rosy glow? Glorious paintings, statues as magnificent as any done by the ancient Greeks and Romans, the beginnings of science, and the recognition, after medieval absorption in a celestial afterlife, of the belief that this world is all we have and that man is the measure of all things.

Think of the Renaissance. Feel the rosy glow? Glorious paintings, statues as magnificent as any done by the ancient Greeks and Romans, the beginnings of science, and the recognition, after medieval absorption in a celestial afterlife, of the belief that this world is all we have and that man is the measure of all things.

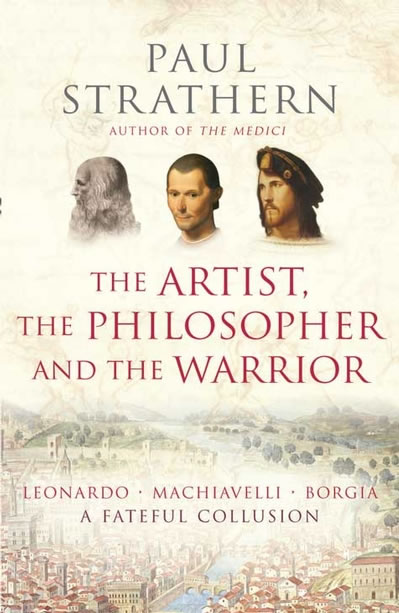

This succinct group biography of Leonardo da Vinci, Niccolò Machiavelli and Cesare Borgia brings late 15th- and early 16th-century Italy alive. It is a salutary reminder that this celebrated period of creativity was also one of intense cruelty and barbarity. Power went to those who grabbed it and held it until it was wrested from them by the knife, the rack or disease.

That the most successful Renaissance tyrants included Roman Catholic popes and their armed militias is an historical fact easily forgotten in the light of today’s innocuous Vatican state. The main subject of this book, Cesare Borgia (1475-1507), the military leader who conquered Northeastern Italy (the Romagna) for the papal powers, was the son of Pope Alexander VI, who acceded to the papal throne in the momentous year of 1492.

That popes should have children was not surprising in the 15th century of the Church which still bans “artificial” birth control. Alexander VI, as Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, sired four offspring. When pope, Paul Strathern vividly portrays from historical records, he enjoyed sex as a spectator sport. With his son Cesare and his daughter Lucrezia at his side, he watched orgies at which naked prostitutes picked up chestnuts with their vaginas before going on to service the male guests.

Like previous popes, Alexander VI placed his male children high in the church hierarchy. Thus Cesare, in 1493 at the age of 18, was made a cardinal. His younger brother Juan, Duke of Gandia, was made leader of the papal forces. However, Juan in 1497 was found with his throat cut – a murder widely attributed to Cesare, who promptly resigned the cardinalate and acquired the military power. He later found a wife in the court of the French king, Louis XII, who went on to invade Milan. One effect of the French invasion was that the gentle Florentine painter, Leonardo da Vinci (then 44) left Milan, but not before leaving a fresco of the Last Supper on a monastery wall.

Borgia, after three campaigns, controlled the Romagna, stretching up to Venice (another city-state). He made his base at Imola near Bologna, which had surrendered to him in 1499. He saw the uses of Leonardo da Vinci, whom he knew to be an expert military engineer, and was looking for work. That Leonardo was in Imola is testified by the remarkable map, a birds-eye view showing every street, he drew while there. Leonardo, who, Strathern speculates, was a gentle vegetarian, must have been appalled by Borgia’s ruthlessness. Yet he went on to help Borgia in many ways, not least by showing Borgia’s army how to cross a river by making an instant bridge from a stack of wood.

At some point he met Machiavelli, the philosopher, who was in the Florentine delegation sent to Borgia’s court. Together the two came up with a mind-boggling scheme to divert the River Arno which flowed past Florence before it reached Pisa, cutting the Pisan link to the sea and therefore depriving it of reinforcements while the Florentine army besieged it. Canals were dug but the project was never completed. Leonardo put aside his designs for a diving suit with which a man might pierce a hole in the bottom of a ship, drowning all the people in it: “I will not publish, nor divulge such things because of the evil nature of men.” Going back to Florence Leonardo rediscovered his delight in painting and in the spring of 1503 began the Mona Lisa. He then returned to Milan, then France where he died in 1519.

Machiavelli too returned to Florence and dreamed of a replica of ancient Rome when Italy was great and united under a forceful leader. Instead with the Medicis returned to power in Florence, in 1513 he was imprisoned and tortured, then exiled on his estate. He did not waste his time.

Machiavelli used Borgia, who had died in battle in 1507, as a model for Il Principe – The Prince – his most famous work, which brought realism into political philosophy. If, he conjectured, a man wants power, he must accept corruption, ambition and greed as realities. He must appear to be moral while retaining power by any available means. Machiavelli was rewarded by finding The Prince – indeed, all of his works – put on the Catholic Church’s first Index of banned books. He was rewarded too by an appointment in the new republican government in 1527 after the deposition of the Medicis; he died the same year.

Strathern’s engaging book is full of wonderful asides. He shows how syphilis brought to Italy by French soldiers was deservedly called “the French disease”. Discussing Leonardo’s vegetarianism, he mentions that the pre-Lenten festivity known as “Carnival” means literally (in popular etymology) “carne-vale” – “Goodbye meat”. Over all, it glides the reader through the intricacies of Italian history and gains a rewarding glimpse of the origins of the present Italy, a variegated, ill-coordinated amalgam of old warring city-states. The Italian disease?

The Artist, the Philosopher and the Warrior is published by Jonathan Cape