One of the first things that any journalist should be taught – or, better yet, figure out for themselves – is the art of personalising a story. While facts and figures are important, stories that consist of nothing else have a tendency to promote eye-glazing in the passing reader. This is especially the case when the numbers are unfathomably vast, and the story is occurring in the proverbial faraway place of which we know little.

One of the first things that any journalist should be taught – or, better yet, figure out for themselves – is the art of personalising a story. While facts and figures are important, stories that consist of nothing else have a tendency to promote eye-glazing in the passing reader. This is especially the case when the numbers are unfathomably vast, and the story is occurring in the proverbial faraway place of which we know little.

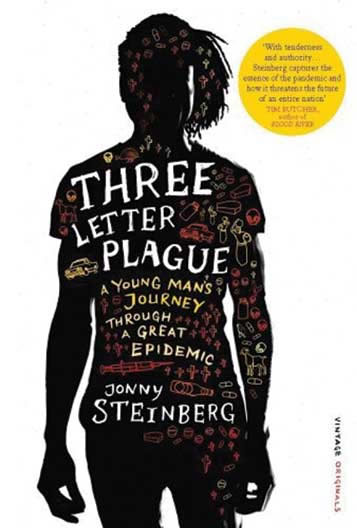

As South African journalist Jonny Steinberg understands, there are few places as routinely overlooked as the continent he was born on, and few of its afflictions as generally disregarded as the one which may be the most crucial: Human Immunodeficiency Virus, or HIV, the three-letter plague. The numbers are, indeed, horrifying to the point of cowing the comprehension: according to the World Health Organisation, roughly 5.7 million of Steinberg’s fellow South Africans are HIV positive. Astutely, Steinberg decides to filter all that through the experience and perspective of one man – and one man, at that, who may not even be HIV positive.

At least as much as it is a book about HIV, and the erratic efforts of South African government and society to come to terms with it, Three-Letter Plague is a book about friendship, race and journalistic ethics – and it’s very good on all four subjects. Steinberg befriends a 29-year-old man called Sizwe Magadla, who keeps a shop in the Eastern Cape village of Ithanga: it says much about the shame still impeding treatment of HIV that both names are pseudonyms, and much more about Steinberg’s punctilious interest in this stigma that the book’s conclusion recounts his conversations with his subject about whether or not it would be proper to blow his cover.

izwe interests Steinberg because he refuses to be tested for HIV. The narrative of Three-Letter Plague is essentially Steinberg’s attempt to figure out why, and by doing so answer the question that nagged him into this project in the first place: why do so many ill, or potentially ill, not accept available treatment? What Steinberg discovers, in his conversations with Sizwe and his induction into Sizwe’s world, is as infuriating as it is complex. There is the lingering conspirazoid suspicion among black South Africans that HIV and/or its treatments amount to a white plot to become a majority of the population. There is a widespread preference for the risible nonsenses of folk medicines and traditional healers. There is what increasingly sounds like criminal incompetence or indifference on the part of South Africa’s government in establishing the networks that would permit the distribution of Anti-Retroviral (ARV) medicines, which, though they do not cure HIV, can commute it from a death sentence to a more or less manageable condition.

As a benchmark for his frustrations, Steinberg also explores the miracles wrought in and around Ithanga by a campaign spearheaded by Médicins Sans Frontières, and a splendidly irascible German doctor (in one of Steinberg’s characteristic canny asides to the reader, he notes: “Of course Hermann is irritated that I am writing a book about a sceptical man on the margins of his programme; for it is surely to be a book about the limitations of his work”). Inevitably, and probably most importantly, what it all comes down to is that most chronically human of reactions to disaster, or the threat of it: denial. Steinberg never places himself above this – a well-timed disclosure about his own relationship with HIV illustrates that he is exploring a failing he recognises in himself.

This is a modestly tremendous book, an example of the very best of reporting: which is to say, that it’s about what it’s about, but about so much more besides.

Three-Letter Plague is published by Vintage