"Daddy, why did Jesus invent butterflies if they die after two weeks?"

"Daddy, why did Jesus invent butterflies if they die after two weeks?"

I just about hit the panic button when my six-year-old son Theo put this question to me not long ago. His mother, who is a Christian, had taught him that Jesus was God. When Jesus's visage appears in a painting or on television, Theo sometimes exclaims, "That's God!" In his butterfly question he seemed to reason, syllogistically, that if Jesus was God, and God created the world and its life forms (butterflies being one of them), Jesus "invented" the winged creatures. Either that or God and Jesus are simply interchangeable in his mind.

"First, Theo, your question presumes that Jesus was God," I responded. "Many people, like mommy, believe he was, but many others don't. It also presumes that there is a God - we don't know for sure that there is." "I think there is," he retorted. "There may very well be a God, Theo. But not everyone agrees on that - there are many people who doubt there is a God. We might never know for sure if there is or not," I told him. "When we die we'll know," he came back. "Maybe," I said. "But maybe not."

The literalism packed into Theo's question alarmed me, but this was by no means my first encounter with the influence of religion on my progeny. My ten-year-old son Elijah enjoys going to church with his mother - not every Sunday, but not infrequently. I've never discouraged it. One Monday morning a few months ago, though, I saw him reading the Bible, a children's Bible he'd been given at his mother's church. In no way did I discourage him from reading it. But I confess (as it were) that I went to work that day a bit preoccupied.

To be sure, I'd always been comfortable with our familial arrangement: our boys have parents with very different views on religion - their mother a Catholic, their father an agnostic humanist. This is only one of the several ways in which our family is "mixed": Nilsa is from Puerto Rico, I from the Midwestern US; she grew up in a working-class family in the countryside, I in a middle-class one in the suburbs; she speaks to the children in Spanish, I in English. Our differences regarding religion must therefore seem, to the kids, par for the course, no?

I've also sensed (hoped?) that having one religious parent and one secular one could be healthy for the boys ("hmm, if mom believes x but dad doesn't, I guess there are multiple perspectives to consider, and who knows which one is right? Maybe none has a monopoly on truth...").

Nonetheless, the sight of Elijah reading the Bible that morning did leave me with an uneasy feeling. Of course it was wonderful to see him reading. And the Bible is in any case a seminal world-historical text: familiarity with it is an essential form of cultural knowledge. Churches, however, don't typically dispense Bibles merely as cultural texts but rather as the Word of God. It was in this register that I worried a bit about Elijah's engagement with the book. And it made me ask myself what exactly I was doing to share, or impart, my secular worldview to Elijah, as a counterbalance to the Catholicism he was imbibing from his mother. She takes him to services. What do I take him to? She has him reading the Bible. What do I have him reading?

I have read all sorts of books with Elijah that I think of as humanistic, broadly speaking: lots of poetry (particularly Pablo Neruda, whose Book of Questions is ideal for children); books like David A White's Philosophy for Kids, and its sequel, The Examined Life: Advanced Philosophy for Kids. I recall feeling especially proud one evening after doing a chapter of Philosophy for Kids, which is designed for discussion between parent and child - I think it was a chapter on the meaning of friendship - followed by some verses of Neruda. I put Elijah to sleep that night thinking to myself, a diet of Aristotle and Neruda for my eight-year old - how cool is that?

Cool though it may be, does it actually counterbalance the influence of the churchgoing and Bible-reading? Or does it operate on a parallel track from it altogether? Does Elijah juxtapose whatever he may be taking away from the philosophy and poetry with the stuff he hears at church? Does he consider one in relation to the other at all? Seeing his head buried in that Bible that morning really made me wonder if I was perhaps approaching the matter too sideways. Maybe I needed to tackle the situation head-on.

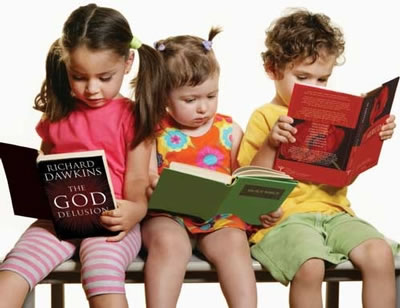

But how? Are there any children's books, I wondered, that directly address religious questions from a humanistic point of view? Not necessarily an anti-Bible, but a strong alternative or counterpart in a secular key.

I called a friend of mine, who works for a humanist charity and is a parent too, feeling sure he would have some sage advice. His response surprised me. Not only did he not know of any good humanist children's books, he said, he didn't like the idea of such a thing. Rather than attempt to counter-indoctrinate kids with explicitly anti-religious messages, he argued, far better simply to expose them to the widest range of reading as possible - weren't Roald Dahl and Dr Seuss essentially humanistic? - and expose them to the manifold religions and philosophies in the world in order to nourish their imaginations and sense of wonder about the Universe, and help them view religion in a comparative context. The antidote I was seeking, he suggested, was to be found in books of evolution and science fiction, not didactic manifestos.

Sounded wise, though I didn't expect to hear it from a full-time, professional humanist. And I was disappointed that he didn't have a ready-made list of books of the sort I had in mind.

The dilemma remained: what if all the science and fantasy and comparative metaphysics fail to do the trick, and Christian literalism, despite my efforts, works its magic on my children's minds? Call me intolerant, but I'll admit it: I don't want to tell my children what to believe or not to believe, but I would be displeased and disappointed if they were to embrace conventional religious views. I just would be. Isn't there a more direct way, I thought, to militate against that outcome?

I turned to Amazon and found that there are several books in this register. Many of them are published by Prometheus Books, an American press with a long history. Within minutes I had found books such as Humanism, What's That? A Book for Curious Kids by Helen Bennett and Dan Barker's Maybe Yes, Maybe No: A Guide for Young Skeptics. I particularly liked the title of this one. Could I have found what I was looking for?

I had liked the idea about exposing the kids to the array of religious traditions. Wouldn't this naturally tend to weaken the notion that any one religion holds the key to Truth? Another friend of mine had challenged this idea - wouldn't this, he asked, merely sanction or naturalise the religious frame of understanding the world? Isn't the message, in effect, "Look at these various religious beliefs and practices - you are free to pick among them"? "What about the millions of people who live without religion?" he asked. "Why not present secular modes of thought alongside the religious traditions?"

He had a point, but since I was already getting some explicitly secular books I added The Kids Book of World Religions to my shopping cart.

Well, we've read the books, but I'm afraid there's nothing terribly interesting to report either about the texts as such or about my children's reactions to them, which have been rather quiet, if not altogether bored - tough to tell, and I'm strongly disinclined to go fishing for their thoughts. I've been tempted, but better, I think, to let them process it all in their own way (assuming the books made an impression at all). The books themselves are a mixed bag: at turns poignant and clunky, clever and awkward. I might re-read them with the boys at some point. Or maybe they'll pick them up themselves and read them on their own. We'll see.

And I might look for other humanist books that engage my children more than this first batch did. Raising my children as a secular father in a society saturated with religion, and in a home that is itself mixed (up?) on the religious question, creates anxiety. But maybe I should just relax. "Kids mostly just want to play with their friends, and religion isn't that big a deal - though it is, unfortunately, to parents," writes Emily Rosa, one of the contributors to the book Parenting Beyond Belief: On Raising Ethical, Caring Kids Without Religion, in an essay evocatively titled "Growing Up Godless: How I Survived Amateur Secular Parenting".

All parents must confront the prospect that if we raise our children to be free, self-confident individuals, they may make choices that we don't like. Tough. The companion volume to Parenting Beyond Belief bears the title Raising Freethinkers. Sounds appealing - I'd like to raise freethinkers. But what if raising my kids to be truly free in their thinking results in their becoming religious? What if my efforts to instill scepticism in them lead them to become sceptical of my humanism? So be it.

All parents must confront the prospect that if we raise our children to be free, self-confident individuals, they may make choices that we don't like. Tough. The companion volume to Parenting Beyond Belief bears the title Raising Freethinkers. Sounds appealing - I'd like to raise freethinkers. But what if raising my kids to be truly free in their thinking results in their becoming religious? What if my efforts to instill scepticism in them lead them to become sceptical of my humanism? So be it.

"Teaching" your children (about) humanism can be a fool's errand, plagued by some the same pitfalls involved in raising children "in" a particular faith tradition. Richard Dawkins has provocatively argued that indoctrinating children with religion is a form of child abuse. But couldn't secularism, as Jeremy Stangroom recently wondered, constitute its own form of indoctrination? Might the attempt to impart one worldview or another to one's children - whether religious or secular - itself be ill-conceived?

And yet one doesn't want to be passive, especially in the American context, in which religion in one form or another constitutes a kind of default position. One can certainly understand the impulse behind the humanism-for-kids books, whatever their faults and limitations, and the desire of secular parents to get their hands on them. They arise from and speak to a very real hunger, whether they satisfy it or not.