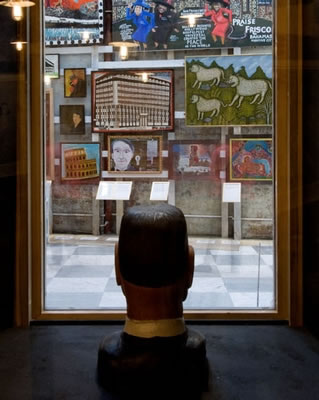

The opening of a new gallery in the swanky confines of London’s Primrose Hill – the hit of the annual Frieze Art Fair in Regent’s Park, according to the London Evening Standard – confirms Outsider Art as the hot new genre in contemporary art. The Museum of Everything is dedicated to the display of “unexpected, delicate and profound” art by “the unknowns of society”, people from the fringes, outside the orbit of the world of art training and appreciation, unrecognised in their time, hidden by poverty, mental illness or their own reclusiveness.

Many of the featured artists are now dead, which is part of the point. In life they never received the recognition or acclaim, this exhibition argues, that their art warrants, “For these artists,” declares one of the handwritten signs that adorn the walls of the tastefully shabby former dairy where this copious private collection is housed, “there are no studios, no press junkets, no art fairs, no magazine spreads.” (A claim somewhat contradicted by the Museum itself, as well as by this spread, but never mind.)

Many of the featured artists are now dead, which is part of the point. In life they never received the recognition or acclaim, this exhibition argues, that their art warrants, “For these artists,” declares one of the handwritten signs that adorn the walls of the tastefully shabby former dairy where this copious private collection is housed, “there are no studios, no press junkets, no art fairs, no magazine spreads.” (A claim somewhat contradicted by the Museum itself, as well as by this spread, but never mind.)

Outsider Art is a bit like folk art, in that the artists are by and large untrained and not from the urban centre, it is naïve in technique and floats free of the dominant art-historical schools of the day, many of its practitioners suffer from mental illness and bizarre obsessions, and some built their own unique worlds in their bedrooms, sheds or on hidden land. Stories, of the artist’s lives and those they create in their work, are central to the appeal.

New Humanist took the tour of the Museum in the company of one of the curators, Liana Goatman, to get the full outside story.

Environmental Artists

Environmental Artists

Nek Chand was a roads inspector in Chandiggarh, the town that Le Corbusier designed in India, and he used recycled materials that he found on the roads to make an entire village on some secluded land. He would cycle around on his bike and fill his basket with old plates and stones. He made hundreds of sculptures, people and animals, and built caves and buildings. No one knew about it apart from a few helpers. All the sculptures have steel armatures which are coated with cement, and while it was still wet Chand inlaid class and ceramics, bangles and fabric balls. As a roads inspector he knew where he could find the materials, and people would tell him about places where he could find broken crockery. After about 15 years the town was discovered by the authorities. He was using the land illegally and at first they didn’t know what to do with it. But they were so amazed by the size and quality of the sculptures that it was protected and became the Nek Chand Foundation. Why did he do it? He came from a village which was put on the Pakistan side of the border in 1947, so he couldn’t visit. He said he wanted to recreate the village, to build his own village where he could find peace. He is a very quiet and dignified man. He’s amazed by the attention his work gets, he’s very modest. He wouldn’t describe himself an as artist.

Visionaries & Mystics

Visionaries & Mystics

Madge Gill was born an illegitimate child in East Ham, London at the end of the 19th century, and spent time in an orphanage. She had a very isolated childhood. Her aunt introduced her to spiritualism and in 1919 she began drawing feverishly, inspired by her spirit guide “Myrninerest” (my inner rest). She drew hundreds of pictures, from tiny postcards to huge sheets of fabric 30 feet long, many featuring the same female figure – possibly Myrninerest, maybe Gill herself. She did receive some recognition as an artist and exhibited locally. She was reputedly offered a show by a classy gallery, but she said that the work was not hers to sell but belonged to her spirit. Many of her works, including hundreds of postcards, were found under her bed when she died. She bequeathed her work to Newham council.

Art Therapy

Art Therapy

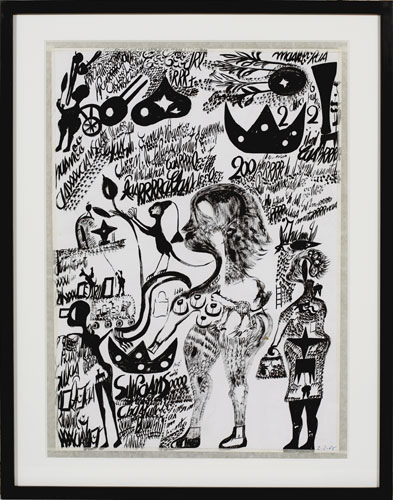

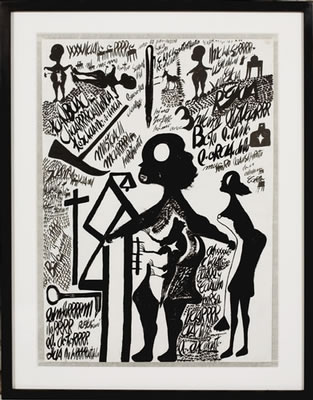

Carlo Zinelli was born in 1919 in Italy. He fought in the Second World War and came back severely traumatised. He became paranoid and delusional and in 1947 was committed to a mental institution in Verona. Conditions were terrible, it was dirty and overcrowded. He began to scratch graffiti on the wall there. Then things improved and they opened an art studio in the asylum. Zinelli began to paint everyday as part of the art therapy programme. His painting developed from very violent stark black and white to more playful colourful work. After 14 years, for some reason he was transferred to somewhere with no studio. There is no evidence that he painted again. He died in 1974.

Visit the Museum of Everything