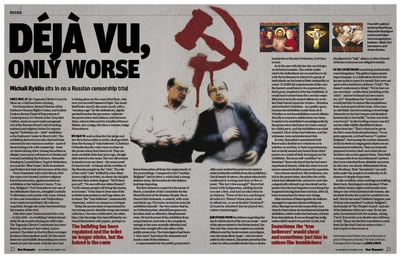

Since May, at the Tagansky District Court in Moscow, a trial has been running.

Since May, at the Tagansky District Court in Moscow, a trial has been running.

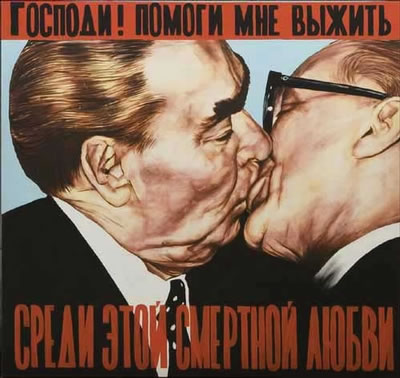

Yuri Samodurov, former Director of the Sakharov Human Rights Center, and Andrei Erofeev, former Head of Department of Contemporary Art Trends at the Tretyakov Gallery, stand accused under paragraph 282 of the Russian Penal Code of inciting national and religious hatred by organising the “Forbidden Art – 2006” exhibition at the Sakharov Center in March 2007. The exhibition featured artworks that had been removed for one reason or another – most of them having to do with censorship – from art shows during 2006. Among the artists on display were many well known in Russia and beyond, including Ilya Kabakov, Alexander Kosolapov, Leonid Sokov, Vagrich Bakhchanyan and the “Blue Noses”. Both Samodurov and Erofeev lost their jobs because of the trial.

From November 2004 until March 2005 the same court hosted another religious hatred prosecution, against another art exhibition at the Sakharov Centre, “Caution, Religion!”. Yuri Samodurov was one of the defendants then too, alongside Ludmila Vasilovskaya and my late wife Anna Alchuk. In that case Samodurov and Vasilovskaya were convicted and fined. My wife was acquitted, though she never recovered from the trauma of the trial.

After four years I have returned for a day – 24 July 2009 – to a building I visited almost daily for six months during my wife’s trial. The Tagansky District Courthouse has been fixed up a bit since I last visited, and repainted. The toilet on the first floor no longer produces that repellent smell. Yet the metal detectors and bailiffs demanding your documents are just the same. And the new trial is taking place on the same third floor, only now you turn left instead of right. The room itself looks exactly the same: small, with a “monkey cage” for the defendants, tightly packed benches for spectators, tables for the prosecution and defence; and between them, almost obscured by tall piles of brown folders, sits a judge, this time a woman, Judge Alexandrova.

We had to wait an hour for the judge and her dirty brown piles to arrive, during which time the throng of “true believers” (Christian Orthodox fanatics who come to cheer on the prosecution) had risen to 60. They are more excitable than four years ago, though their hatred is the same. The two old women in headscarves are there – the same ones? It’s hard to tell – to blame all the troubles of the Russian people on the “yids”. The role of the crafty “yids” is filled by a few silent human rights activists, at whom the old girls directed their ardent slogans: “We’ll show you yet!”; “No one will ever defeat Russia!”; “God’s chosen people will bring the enemy to its knees.” From time to time one of the activists loses patience and begs them not to shout. The “true believers”, momentarily chastened, switch to a temporary whisper.

We had to wait an hour for the judge and her dirty brown piles to arrive, during which time the throng of “true believers” (Christian Orthodox fanatics who come to cheer on the prosecution) had risen to 60. They are more excitable than four years ago, though their hatred is the same. The two old women in headscarves are there – the same ones? It’s hard to tell – to blame all the troubles of the Russian people on the “yids”. The role of the crafty “yids” is filled by a few silent human rights activists, at whom the old girls directed their ardent slogans: “We’ll show you yet!”; “No one will ever defeat Russia!”; “God’s chosen people will bring the enemy to its knees.” From time to time one of the activists loses patience and begs them not to shout. The “true believers”, momentarily chastened, switch to a temporary whisper.

Today the prosecution is represented by two young men in shoulder straps decorated with stars. One has a white shirt, the other blue. Like the judge they had efficiently surround themselves with papers, perhaps to fence themselves off from the tragicomedy of the proceedings. Compared to the “Caution: Religion!” trial in 2004-5, which had a strong defence team, the benches for the defence look less imposing.

The first witness is a priest by the name of Burov, a member of the Committee for the Moral Revival of the Russian People. He arrives in full vestments, a cassock, with cross and black cap. Of course, he had not seen the exhibition himself – the very notion that he, an Orthodox priest, should have gone was brushed aside as offensive, blasphemous even. He had learned of the exhibition from acquaintances, had seen a few snapshots, enough to became mortally offended and drive him straight off to the office of the public prosecutor. The investigator had been a “nice man”, had taken his statement and made a note of the evidence.

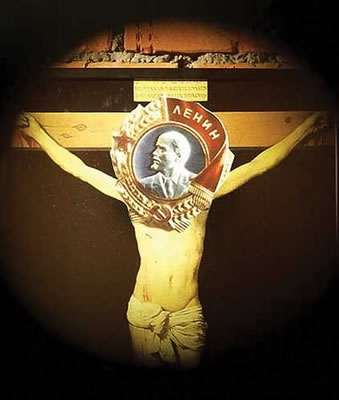

A representative for the public prosecutor’s office now invited the priest to his desk in order to identify exhibits from the exhibition. Out of nearly 30 pieces, the priest reluctantly confessed to having seen four or five at most. “But isn’t this enough?” Burov bellowed with indignation, adding that he was not a fool, and had an education in art history. “None of this has anything to do with art. Weren’t these pieces made to offend me, as an orthodox Christian?” (It must be admitted that he played this rather convincingly.)

Questions from the defence regarding the era in which much of the art was made – most of the pieces related to the Soviet period, the ’60s and ’80s, when the context was entirely different and the Soviet system, not religion, was a far more likely target – were brushed aside by the witness. The priest permitted the artists no other possible motive than a desire to poke fun at Russian Orthodoxy, be it then or now.

Questions from the defence regarding the era in which much of the art was made – most of the pieces related to the Soviet period, the ’60s and ’80s, when the context was entirely different and the Soviet system, not religion, was a far more likely target – were brushed aside by the witness. The priest permitted the artists no other possible motive than a desire to poke fun at Russian Orthodoxy, be it then or now.

As is the way with the law the case hinges on technical matters. The article under which the defendants are accused has to do with the incitement to hatred of a group of individuals on the basis of their nationality or creed. To fulfill the requirements of the case the hatred would have to be expressed by a third party, inspired to it by the exhibition. It would have to have been the case that some third party actually caused offence to or visited their hatred upon the victims – Russians and orthodox Christians – in a public space, because the exhibition made them do it. Whether or not the exhibition caused offence directly to anyone is neither here nor there. It needs to be established unambiguously by the prosecutors that harm has been caused by a third party, and the exhibition was what caused it. Most of the true believers, and the witnesses, have misunderstood this.

In vain, Samodurov questioned both Burov and a further two witnesses as to whether or not they, or their acquaintances, had actually sensed any hatred from third parties as a result of their having put on the exhibition. The more self-confident “art historian” Burov declared that he had never experienced hatred, while the other two witnesses seemed afraid to answer the question.

One witness stood out. Her testimony, central to the prosecution, describes the works which had offended her, and yet in court she categorically refused to go into detail on the pretext that she had forgotten everything that happened during that time and had, after all, been traumatised by those very things.

After one hour of interrogation the defence managed to squeeze almost nothing out of her. She kept secret the name of her own church; from whom she had learned about the exhibition; which works she had seen, or knew from descriptions. It was as though her indignation didn’t need to be put into words, and she played it in “holy” silence, in direct breach of the law (witnesses are obliged to testify).

In the courtroom something unthinkable was taking place. The gallery began speaking in tongues. As a defendant stood or his lawyer made to open his mouth they were set upon with a hailstorm of abuse: “Fool!”; “He doesn’t understand a thing”; “We’re here on our own land – unlike these [nodding at the ‘yids’] – and we’ve found our own teachers, too!” Sometimes the “true believers” would just hiss in unison like bumblebees from various parts of the room. All at once an old biddy started swearing so loud Judge Alexandrova lost her temper and shrieked hysterically at the bailiff, “Get her out of the courtroom!” As the battling woman was led out her allies visibly disaffiliated themselves from her: “That’s what you’ve got to do. She’s some kind of madwoman.” It was quite apparent, as it had been at “Caution: Religion!”, that among the various elements of this hysterical congregation there was no fundamental solidarity. They are instantly prepared to betray their own when the authorities take action against them. Their faith is inseparable from the informant’s instinct they have inherited from atheistic ancestors (in this they are clearly differentiated from the Muslims). Their “fanaticism” can only exist under the auspices of authority; in its absence it simply evaporates.

In the courtroom something unthinkable was taking place. The gallery began speaking in tongues. As a defendant stood or his lawyer made to open his mouth they were set upon with a hailstorm of abuse: “Fool!”; “He doesn’t understand a thing”; “We’re here on our own land – unlike these [nodding at the ‘yids’] – and we’ve found our own teachers, too!” Sometimes the “true believers” would just hiss in unison like bumblebees from various parts of the room. All at once an old biddy started swearing so loud Judge Alexandrova lost her temper and shrieked hysterically at the bailiff, “Get her out of the courtroom!” As the battling woman was led out her allies visibly disaffiliated themselves from her: “That’s what you’ve got to do. She’s some kind of madwoman.” It was quite apparent, as it had been at “Caution: Religion!”, that among the various elements of this hysterical congregation there was no fundamental solidarity. They are instantly prepared to betray their own when the authorities take action against them. Their faith is inseparable from the informant’s instinct they have inherited from atheistic ancestors (in this they are clearly differentiated from the Muslims). Their “fanaticism” can only exist under the auspices of authority; in its absence it simply evaporates.

In the corridors, when nothing was holding them back, they leaped and shouted. When an elderly human rights activist said something to one of the hysterical old women, she shrieked that for his words he would burn in hell. Next to her stood Vladimir Sergeyev, one of those who smashed “Caution: Religion!”, the founder of “The People’s Guard” and one of the initiators of this new case. To my surprise, he reasoned with the woman, saying, “Don’t. It is not for us to decide who will burn in hell.” These are the first conciliatory words from his lips that I had occasion to hear. I don’t expect to hear more.

Samodurov and Erofeev face up to five years in prison if they are convicted. The trial continues.

Translated from Russian by John Amor