Letters to the editor: send us your thoughts for our letter pages by email to editor@newhumanist.org.uk

Fancy a threesome, anyone? First, you’d better make sure you’ve got the right equipment, judging by this woman’s fond recollection of foreplay with a swinging couple:

“While I have had both hot wax and the business end of a riding crop applied to my flesh before, it was a new experience to have it done with my legs in the air and lit candles plunged into me, dripping over my torso. After two hours, he entered her and, using his cock like the dome in my fantasy, drove her face-first into my pussy.”

Doesn’t that sound like fun, girls? And if you don’t recognise the origins of that edifying revelation you must have been sheltering for the past three months in some humanist monastery. It comes, of course, from the pen of the secret blogger Belle de Jour, who recently revealed her true identity to a media uproar of shock and awe. For this happy hooker was no victim, no sleazy madam, not a crook or a charlatan nor even, as so many male journalists had fantasised, an overimaginative man. Belle de Jour, you’ll remember, turned out to be Dr Brooke Magnanti, a very attractive, highly educated research scientist. And since her self-outing she’s admitted rather missing her exotic lifestyle.

Doesn’t that sound like fun, girls? And if you don’t recognise the origins of that edifying revelation you must have been sheltering for the past three months in some humanist monastery. It comes, of course, from the pen of the secret blogger Belle de Jour, who recently revealed her true identity to a media uproar of shock and awe. For this happy hooker was no victim, no sleazy madam, not a crook or a charlatan nor even, as so many male journalists had fantasised, an overimaginative man. Belle de Jour, you’ll remember, turned out to be Dr Brooke Magnanti, a very attractive, highly educated research scientist. And since her self-outing she’s admitted rather missing her exotic lifestyle.

The case of Belle de Jour has shocked not only the usual brigade of moral crusaders, Bible bashers and bishops. It has also highlighted a stark division of attitudes among feminists. Traditionally, the radical feminism which emerged in the 1970s has held an uncompromising position: prostitution is the most extreme example of a society where women are commodified as sex objects. Men who use their services are objectifying and thereby dehumanising them.

This was the view expressed by Harriet Harman at last year’s Labour Party Conference: “We know that prostitution is not work,” she declaimed. “It’s exploitation of women by men – often women who have mental health problems or drug or alcohol addiction. So we’re introducing a new criminal offence of having sex with a prostitute who’s being controlled by a pimp.”

So the Policing and Crime Act, which was passed in November, makes it illegal to pay for “sexual services of a prostitute controlled for gain”. It also strengthens existing legislation on loitering and requires that anyone convicted of such an offence must attend rehabilitation sessions.

Those opposed to the Act, most vocally represented by The English Collective of Prostitutes, argue that these measures will drive prostitution further underground and offer women less protection. They point out that by making it easier for the police to close down brothels the new Act will actually make prostitutes less safe, since women working together or in brothels are far more likely to be protected.

Feminists like Harriet Harman, who regard prostitution as a betrayal of women, have always found it difficult to square their sexual politics with the views of those who see it as just another life choice. They are perplexed by the so-called “post-feminist” position, espoused by many younger women who are gloriously unjudgmental: they have fun with pornography, see nothing wrong with lap-dancing or topless modelling and have no problem with prostitution if that’s what women want to do. They just don’t buy the idea that men are the oppressors; for them, men are more likely to be the victims. If they’re prepared to pay, why shouldn’t women take their money? In response Dr Shasha Rakoff, director of the anti-prostitution organization OBJECT, fulminates against “the re-packing of one of the oldest forms of exploitation – prostitution – as empowerment for women”.

These conflicting views seem to divide Europe, too. In the Harman camp is Sweden, which in 1999 criminalised the purchase but not the selling of sexual services. The reasons behind this law are the Swedish government’s belief that prostitution is a form of exploitation of women and male dominance over women. Which is a position tricky to defend since the law applies equally to both sexes, regardless of the gender of the buyer.

These conflicting views seem to divide Europe, too. In the Harman camp is Sweden, which in 1999 criminalised the purchase but not the selling of sexual services. The reasons behind this law are the Swedish government’s belief that prostitution is a form of exploitation of women and male dominance over women. Which is a position tricky to defend since the law applies equally to both sexes, regardless of the gender of the buyer.

Sweden’s example has been copied by Norway and Ireland. Meanwhile, in eight other countries – Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Greece, Turkey, Hungary and Latvia – prostitution is legal though the extent to which brothels are condoned or policed does vary.

It’s difficult to estimate the effects on the trade of these measures. There are claims that prostitution in Sweden has been reduced significantly by the legislation, though this is disputed since it’s so difficult to establish reliable evidence. And statistics on prostitution are notoriously conflicting. Those arguing for the decriminalisation of prostitution will point to research like that of Teela Saunders, whose 1999 study of sex workers in Leeds found that 75 per cent of them were middle-class mothers who had worked as nurses or care workers. They mostly regarded their bedroom transactions as a similar kind of service. But this was a study of only 55 women in a particular area and there’s no evidence that it is typical.

Meanwhile, the tireless work of Julie Bindel in investigating the sex trade tells a less happy story. In a 2008 study, The Big Brothel, she and her co-author Helen Atkins recruited male friends and colleagues to telephone brothels, posing as potential punters, with a list of questions including “What nationalities are on offer tonight?”, “Do the girls do anal?”, “How about oral without a condom?” and “What age are they?”

“We wanted to look at what really goes on in brothels – how much control the women really have; whether there is evidence of trafficking; if local councils are giving licences for saunas and massage parlours when it is clear that they are brothels; and how the sex industry is growing and evolving,” Bindel explained.

“During 120 hours of telephone calls, we established the following: at least 1,933 women are currently at work in London’s brothels; ages range from 18 to 55 (with a number of premises offering ‘very, very young girls’); prices for full sex start at £15, and go up to £250; and more than a third of the brothels offer unprotected sex – including, in some cases, anal penetration. The lowest price quoted for anal sex was £15. ‘Come along and bring your mates,’ said one brothel owner. ‘We have a Greek girl who is very, very young.’ While kissing used to be off-limits for women selling sex, it can now be bought for an extra tenner.” This study’s portrait of London’s prostitutes is a very far cry from the expensive, champagne-fuelled, perfumed high life described by Belle de Jour, whose work took her to top hotels with fabulous dinners funded by extravagantly rich – if demanding – clients.

Bindel’s subjects all reported having felt degraded and violated while selling sex. This, she claims, tallies with previous research: one large US study on prostitution and violence found that 82 per cent of women had been physically assaulted since entering the trade, with many having been raped. More than 80 per cent were homeless, and a majority, on and off-street, were addicted to illegal drugs and/or alcohol. Bindel maintains that most UK research has also found that prostitutes routinely face sexual and physical violence from pimps and punters, but have little or no “workplace” protection.

Bindel’s research was commissioned by the Poppy Project, a British organisation that offers support for women trafficked into prostitution. But their assumption that this is a widespread and growing evil was questioned by Nick Davies in an article in the Guardian last October. Statistical evidence, he reported, had been massively inflated, with the help of the tabloid press, from hundreds to thousands to a ludicrous 25,000 invented by the Daily Mirror but then repeatedly quoted until it became the accepted truth.

And the Big Brothel study, he claimed, had been condemned in a joint statement from 27 specialist academics who complained of flaws in the way the data had been collected and that it was “framed by a pre-existing political view of prostitution.”

His article sparked a furore, as if he’d challenged a sacred truth. But why were so many people so eager to accept what appears to be a largely invented or at least hugely exaggerated sydrome? Perhaps it’s just easier, more comfortable to believe that rather than choosing freely, prostitutes are vulnerable, victimised women tricked and brutalised into a life of sin.

This characterisation stems from attitudes which began to emerge in the late 1840s, when what became known as “The Great Social Evil” was becoming a cause for concern among social reformers. The pioneering journalist William Acton, in his landmark study of Prostitution, railed against the untramelled exploitation of women in extreme poverty, while campaigners like Henry Mayhew and Charles Booth were horrified not just by the plight of prostitutes but by the decadence of a society that could tolerate such immorality. And it was at this time that the Prime Minister William Gladstone embarked on his nocturnal adventures, tracking down ladies of the night in order to rescue them.

This view of prostitutes as victims in need of rescue was frequently portrayed in contemporary literature, in works like Thomas Hood’s poem “Bridge of Sighs”, which exhorts the reader to forgive the fallen woman, to “take her up tenderly”, Elizabeth Gaskell’s novel Mary Barton and Stephen Crane’s short novel Maggie: Girl of the Streets, which traces the downfall of an innocent creature whose corruption leads to her death.

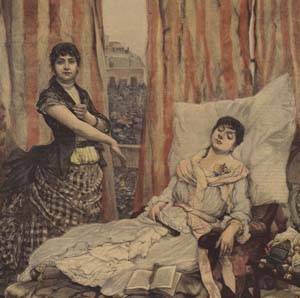

None of these unfortunate victims has much in common with Belle de Jour and her happy high life. But she, too, has a noble fictional pedigree. Belle is a modern version of that stock figure of literature, art and music: the courtesan. High-class society ladies of the night are often portrayed in literature as powerful dominatrixes – like Violette Valery, heroine of Verdi’s opera La Traviata. Having broken the hearts of a string of rich lovers, Violette falls in love with Alfredo only to die of tuberculosis – the killer of choice for prostitutes. Frederick Ashton’s ballet Marguerite and Armand, immortalised by Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev, opens with the courtesan Marguerite on her deathbed. And while Emil Zola’s Nana enters the sex trade in order to persecute and punish men, she too ends up coughing blood and dying a horrible death as her own punishment.

But while Victorian literature sentimentalised the fallen woman as a victim to be pitied, there was at the same time a common belief that prostitutes, no matter how elevated their clients, were corrupt and unclean. And that was what prompted Parliament to pass a series of Contagious Diseases Acts, starting in 1864, which allowed the police to force any woman suspected of venereal disease to submit to its inspection. And it was in response to this brutal measure that began a different kind of campaign. Appalled by the double standard which condemned women but protected and condoned men, Josephine Butler led her famous crusade to repeal these draconian laws, adding a pro-women, proto-feminist voice to what had until then been a more divinely inspired anti-prostitution lobby.

A similar alliance seems to have emerged today. Nick Davies suggested that the tide of misinformation surrounding the subject of sex trafficking had been used and played upon by what he termed “an unlikely union of evangelical Christians with feminist campaigners”.

Ouch, that hurts. Because it’s always unnerving for feminists to find themselves in the same unsavoury bed as religious fundamentalists. But while we may find common ground in our condemnation of prostitution, our reasons are very different. The women’s liberation movement of the 1970s, which so formed the sexual politics of women like Harriet Harman, was all for sexual freedom. We wanted to unleash ourselves from the very constraints which had been imposed by the patriarchy – to have sex whenever we wanted, with whomever we wanted and without guilt or fear. Religion, on the other hand, preaches the virtues of celibacy and monogamy and requires women to be the chattels, the property and the sexual slaves of men. Both views appear to be challenged and reinforced by the starkly disturbing installation currently showing at the National Gallery – a recreation of Amsterdam’s red-light district. In The Hoerengracht by Ed and Nancy Kienholz life-size figures loom out of the darkness, through smeary, red-lit windows. The 11 models have been fashioned from plaster casts but their heads are those of shop dummies and their faces are blank, featureless and encased in glass-fronted boxes. There could be no more telling image of the dehumanising effects of prostitution. And yet Nancy Reddin Kienholz denied that this was the intention. It was, she said, “a piece for voyeurs” and “not against prostitution, but rather for prostitution”. She said it was “a kind portrait. It has a calmness and a contemplativeness about it.”

But her partner Ed Kienholz, who died in 1994, had made an earlier brothel installation on his own in the 1960s which was a much more brutal, politicised work. The madam has a boar’s skull for a head and the girls are dismembered, or made out of rubbish bins and bedpans.

Whether or not you interpret Hoerengracht as an ideological protest, Reddin Kienholz believes that its most salutary effect is to provoke debate about prostitution. “Why lie about it? Why pretend [prostitution] isn’t going to exist? The only thing you do is put it underground and make it less safe for everybody. Less safe for the girls, less safe for the men, less safe for the community. It’s going for legalisation, because I don’t think it’s a sin. I believe that having open brothels is much safer for your mother, your sister, your daughter, because it’s available. I think you have fewer rapes.”

And this is a view that would be warmly endorsed by Elizabeth Posani, an epidemiologist who has worked extensively in Asia and Africa interviewing prostitutes and drug users in an attempt to establish how AIDS is transmitted and how it can be curbed. In The Wisdom of Whores she makes a passionate case for the separation of morality from policy. Indeed, she demonstrates forcefully how the moral position of Christianity, which forbids sex before marriage, promotes celibacy, recoils from physical lust as a moral precept, can, when taken to extremes, be deadly.

Her evidence is overwhelming. When the Bush administration chose to funnel millions of dollars into health programmes in Africa to combat AIDS, much of the funding was confined to Christian projects which preached abstinence. Sex outside marriage was not to be condoned. And so, despite the evidence that use of condoms massively reduces the risk of HIV infection, the practice was not promoted because it was thought to promote promiscuity. And even though prostitution is known to be a major factor in the spreading of HIV, American’s aid programmes are committed not to encouraging the use of condoms by prostitutes, but to abolishing the practice altogether.

One way of enforcing this strategy is Congress’s “loyalty oath”, requiring that anyone taking any money from the US government for AIDS work has to sign a statement saying that they oppose the practice of prostitution. Which means that US money is prevented from targeting one of the main activities known to spread the disease. “No other country to my knowledge,” Pisani fumes, “forces its ideological-theological-political agenda down other people’s throats in quite the same way.”

It is, of course, the religious lobby that has dictated this policy. But the Church is not alone in expressing repugnance at the practice of selling sex. It’s understandable that many are revolted at the prospect of an expression of love and intimacy being debased into a commercial transaction. And that’s why it’s tempting to classify prostitutes as one group and prostitution as one single, ugly stereotype. But in her excellent book Pisani challenges this simplification by exposing the many different reasons people sell sex – from those who do it for the money, as an alternative to even more unsavoury jobs, those who regard it as a social service, those who (a limited number, she believes) have been coerced into it. And, let’s face it, some people do it for fun.

One of the most arresting of her forays into the underworld was among the “waria” of Indonesia. These are prostitutes who come over as women but are actually men. They sell sex to men without necessarily being gay themselves. One of Pisani’s respondents explains that men often take to the streets because it’s a guaranteed way to achieve lots of orgasms. And men always like that. At the same time, their customers would often deny that they are homosexual since using a waria doesn’t really count. “Don’t think that because I go to a banci (waria) I’m a fag,” one informant explains. He’s happy to turn a few tricks with men occasionally and also sometimes buys sex from waria. He does it, he claims, to protect his girlfriend. Who also, by the way, does a little street work from time to time.

“So here we have a self-proclaimed heterosexual guy who has unpaid sex with a woman who sells sex to other men, while himself also selling sex to other men and buying it from transgendered sex workers,” comments Pisani, adding drily: “The truth is, real people don’t have sex in boxes.”

Again and again she points to the prejudices and principles which prevent accurate research and, even more importantly, practical advice from being relayed to the most vulnerable. If AIDS is to be eliminated, she argues, there has to be better control of prostitution, even if that can seem harsh. In China, for example, HIV-testing of prostitutes is mandatory. In Thailand, prostitutes are told by the government to refuse to have sex without a condom, and they are routinely screened.

Again and again she points to the prejudices and principles which prevent accurate research and, even more importantly, practical advice from being relayed to the most vulnerable. If AIDS is to be eliminated, she argues, there has to be better control of prostitution, even if that can seem harsh. In China, for example, HIV-testing of prostitutes is mandatory. In Thailand, prostitutes are told by the government to refuse to have sex without a condom, and they are routinely screened.

Regulation and monitoring are the best way to protect prostitutes not just from AIDS but from the many other dangers they face, from disease to violence, theft to coercion to murder. And because it’s recognised that street-work is the most hazardous form of prostitution, more enlightened regimes tend to operate informal controls. In Utrecht, for example, Julie Bindel visited Europe’s oldest “tolerance zone”, where the officer responsible for policing it explained that having a designated area helps to keep women safe. “They have to come to the police station to register before starting work, so we can make sure they are not trafficked or underage. Also, we know who to look for if they disappear.”

Similar semi-formal protection zones operate in many other countries. In Senegal, for example, as in many former French colonies, prostitution is regulated so that working girls can easily access screening and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases. And in Jakarta, where the waria ply their eccentric trade, there’s a well-organised network that works in tandem with district health officers, covering each of the city’s major districts.

There’s no conclusive evidence of the effectiveness of any of these different strategies. But Elizabeth’s Pisani does make a refreshingly humane and practical plea for putting health first, putting women first, and squashing the forces of fundamentalism that seek to punish, criminalise and forbid. That, she argues, is the route to murder.

“I went to Sunday School as a child, and I still go to church every now and then,” she writes. “But I am completely unable to understand religious convictions or moral ideologies that stand in the way of saving hundreds of thousands of lives.”

Letters to the editor: send us your thoughts for our letter pages by email to editor@newhumanist.org.uk

All images by Edward and Nancy Reddin Kienholz from the installation Kienholz: The Hoerengracht at the National Gallery, London until 21 Feb 2010