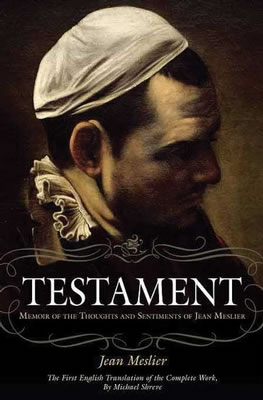

Testament by Jean Meslier, translated by Michael Shreve (Prometheus, £19.99)

Testament by Jean Meslier, translated by Michael Shreve (Prometheus, £19.99)

It’s curious that it has taken nearly 300 years for Jean Meslier’s only work to be translated into English. After all, apart from being perhaps the first European since Roman times to put his name to an overtly atheist document, Meslier was an early agrarian socialist and an anti-monarchist. Furthermore, his atheist credentials were excellent, since he passed his entire adult life as the well-loved priest (pro oppressed peasants, anti wicked squire) of Etrépigny, a tiny village in North-East France. Too scared to speak his mind to anyone during life, in 1729 he left by his death-bed three copies of a sarcastic and well-referenced denunciation of supernatural beliefs. He called it a Mémoire of his thoughts and sentiments about the religions of the world but it is often referred to as his Testament. “All religions are nothing but errors, illusion and imposture” is a typical chapter heading. “The wisdom and learning contained in the so-called holy books are only human” is another. To read Meslier is to read earlier, hayseed incarnations of Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris. There’s nothing new about the “new atheists”.

Despite his modest library and apparent lack of intellectual company, he criticised the many errors and inconsistencies in the Bible well before German theologians got round to it over a century later and over two centuries before Catholics were officially allowed to in 1943. “What certainty do we have that the four Gospels ... were not corrupted and falsified, as we see happen to so many other books even today?” We also find proto-evolutionary thinking (Nature “acts blindly... without knowing what it is doing or why it is doing it”); even some proto-Malthusian anxieties. All very modern, as is his defence of divorce when domestic strife makes children miserable and parents “give them bad examples every day and fail to educate them ... in the arts and sciences as well as in good manners”. Meslier himself had a young “housekeeper” (he passed her off as a cousin) and evidently had relaxed views about sex. Though not a vegetarian, he deplored the prevalent brutality towards farm animals.

In part, his neglect may be because of a not entirely dissimilar book called Common Sense, wrongly attributed to Meslier since the 1790s and still published under his name. In some ways, Common Sense is better written but its real author was an amiable aristocrat, the Baron d’Holbach, who wisely published everything pseudonymously and almost certainly rejected Meslier’s radicalism, which was briefly recognised during the Revolution that followed d’Holbach’s perfectly timed death in 1789. In contrast, Voltaire said that Meslier wrote “like a carthorse”. Despite a few flashes (I like “le dieu de pâte et farine”/ “the god of dough and flour”) it is very repetitious. Pejoratives usually come in threes, like Neil Kinnock on cider. Even his most famous (though often misattributed) phrase, “I would like to see the last king strangled with the guts of the last priest,” is not his own, he tells us.

Disgracefully, Voltaire published, in 1761, a much shortened version of the Mémoire that made Meslier appear a deist, like Voltaire himself. It excised all reference to Meslier’s anti-monarchism and egalitarianism (both of them anathema to Voltaire), presenting him as a death-bed convert rather than a lifelong disbeliever.

Michael Shreve’s translation is faithful but fairly literal and thus shares the faults of the original, even though he has omitted “a number of repetitious words and phrases”. There are several jarring anachronisms – “suckers”, “divvy-up”, “low-lifes”, “big deal” and (probably rather confusing if you don’t know your Gilbert and Sullivan) “Grand Pooh Bah”. And one surely doesn’t have to be a paid-up Christian to feel irritated by the translation of “whited sepulchres” (sépulcres blanchis) as “blank graves”.

The French philosopher Michel Onfray contributes a characteristically robust introduction (“The war song of an atheist priest”) noting the hints of internationalism, anarchism and even feminism in Meslier’s philosophy. If you want your Meslier untranslated, another French philosopher, Hervé Baudry, has recently produced the only currently available edition of the original manuscript (based on the late 18th-century La Haye text). It’s in three volumes (Editions Talus d’Approche, 2007) but quite reasonably priced and has an extensive bibliography