“What is the definition of a good person?” Wang Jisi, dean of the School of International Studies at Peking University, asked at a graduation address in July. His answer: “He does not cheat in exams, or plagiarise another scholar’s work, or cut corners in construction projects, or sell fake goods or accept bribes.” All fairly uncontroversial, you might think, especially considering the occasion. But, in fact, Wang was bravely addressing an issue that surfaces almost every day in the Chinese media. He was taking a stand in the continuing battle between those who uphold academic and scientific values and those others who can still achieve high status and rewards in China from peddling pseudoscience.

One way to capture the size and scope of this battle is through an examination of the fortunes of two men whose names have, over the last two months, been almost inescapable in newspapers, magazines, microblogs and television debates: Zhang Wuben and Tang Jun.

Zhang Wuben is a 47-year-old nutritional therapist from Beijing, whose best-known claim, elaborated in his book Cure the Diseases You Get from Eating by Eating, is that consuming half a kilogram of mung beans every day can cure diabetes and short-sightedness, while eating five times that amount improves a patient’s chances of surviving various cancers. A frequent guest on television talk shows, his clinic was so popular that regular 300-yuan (£29) consultations, which lasted ten minutes, were booked up until 2012. Patients who wanted a fast-track service could pay 5,000 yuan (£483) for an emergency appointment with the health guru.

However, public sentiment turned against Zhang after the price of mung beans tripled, reportedly due to the popularity of his health advice. Rumours spread that he was hoarding beans and speculating on rising prices. Then attention turned to his resumé: Zhang, who opposes the use of conventional medicines, had said he was descended from three generations of Traditional Chinese Medicine specialists, but it turned out that he used to be a textile worker, like his father before him. The Chinese Ministry of Health denied he had the “advanced level nutritionist qualification” that he claimed on his website. The authorities in Beijing tore down Zhang’s ornate headquarters near the Olympic stadium, claiming it had been built illegally.

Then there is Tang Jun, motivational speaker and high-profile CEO of New Huadu Industrial Group, who, early on, was also widely feted in the Chinese media. China Radio International lauded his “genius” and (in a characteristically mangled Chinglish phrase) his “ice-breaking success”. But his reputation has since received a public battering. Patents he claimed to have filed did not exist. Neither did Tang’s purported PhD from the California Institute of Technology. His degree was from an unaccredited “diploma mill” called Pacific Western University. This revelation added an ironic twist to the title of Tang’s autobiography, My Success Can Be Replicated.

What these two cases also have in common is the role played by China’s science advocates – such as Fang Xuanchang, science and technology editor at Caijing magazine, and the biochemist-turned-columnist Fang Shimin (no relation, better known by his pen name Fang Zhouzi), who runs the influential (though frequently blocked) watchdog website New Threads.

Fang Zhouzi, sometimes called the “science cop”, claims to have exposed more than 900 cases of academic fraud in China. It was his investigation that brought to light the controversy around Tang Jun’s qualifications. Tang has since said he will sue Fang for libel – and it’s not the first time he has faced such a threat. In 2006 Fang dismissed as unfounded the claim that the academic Liu Zihua had used ancient Chinese philosophy to discover a tenth planet in the solar system. Despite the fact Liu had already been dead for 14 years, his family successfully sued Fang, fining him 20,000 yuan (around £2,000).

This libel judgement led Song Zhenghai, of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute for the History of Natural Science, to launch a petition to remove the term “pseudoscience” from the country’s science popularisation law, claiming Fang had used the term to help stifle “innovative sciences based on traditional cultures”. The petition was unsuccessful, although it was signed by 150 advocates of traditional theories in science and medicine. And while the censorious use of libel laws to stifle legitimate journalism and debate is worrying, some of the other reactions to the Chinese rationalists have been more shocking, veering into anger, paranoia – and even violence.

A notable example occurred after maverick philosopher Li Ming claimed in 2006 to have found a new way to solve a mathematics problem known as the four-colour theorem, “under the shared guidance of [Daoist philosopher] Laozi and [Immanuel] Kant”. (This theorem states that a contiguous map requires no more than four colours to fill the different regions of the map, so that no two adjacent regions are of the same colour.) Fang Zhouzi was sceptical, and wrote on his website that Li was a crank. So Li replied by publicly proposing a “civilised duel to the death”: if the philosopher could not crack the theorem, he would commit suicide. If he succeeded, Fang Zhouzi should kill himself. Fang declined the bet, saying it was unscientific and inhumane. Li failed to crack the theorem.

Some responses have been still less “civilised”. Earlier this year, Fang Zhouzi appeared alongside fellow science journalist Fang Xuanchang on a television debate about earthquake prediction. An official from China’s national earthquake administration spoke positively on the programme about parrots that can predict tremblors and the paranormal abilities of a man who claimed he heard ringing in his ears before the April earthquake in Yushu, northwest China. Ren Zhenqiu – a scholar formerly at the Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, who argues that science should not be based solely on repeatable experiments and endorses a traditional philosophy known as the “Eight Diagrams” – accused the science activists of taking money from the United States government intended to stifle Chinese innovation. After the recording, Fang Zhouzi claimed on his blog, Ren Zhenqiu said he was a “big Chinese traitor” and threw a punch at him.

Then someone tried to kill Fang Xuanchang. On 24 June, Fang finished work around 10pm and began his walk home. Half an hour later, nearing his apartment in Beijing, he felt a sudden blow, which he initially mistook for a football bouncing off his back. Fang turned to see two large men behind him brandishing steel bars. He tried to run away – and then to shield himself – as the men struck him repeatedly across his back and head. As Fang stumbled towards a passing taxi, his clothes soaked in blood, the attackers left the scene. That night at Beijing’s Navy General Hospital, doctors stitched a five-centimetre wound on the back of his head. His assailants behaved like professionals, Fang told me, executing the brutal attack in about four minutes and showing little concern about passersby. “Their goal was clear,” he said in an email message on 30 June. “That was to kill me on the spot, or stop me from reaching the hospital in time, so that I would bleed to death.”

No one knows who tried to kill Fang Xuanchang and few people seem to care. More than a month later, the attackers remain at large, despite Caijing magazine’s best efforts to involve the police and the All China Journalists Federation. Nor has this been the end of the threats. On 2 July, Fang Zhouzi wrote on his Sina microblog that he had received a threatening phone call. “Be careful in the next few days,” the voice said. “Someone is going to fix you.” In comparison to the controversies around Zhang Wuben and Tang Jun, there has been little coverage of the beating: it was reported in brief in the Beijing newspapers, but no reports asked why someone might want to attack a science journalist. This is hardly surprising – for Chinese journalists, the message of the attack is clear: don’t go near the subject, or you might be next.

But the debunkers have not fallen silent, and upon encountering Fang this is not surprising. I first met the 37-year-old editor about a month before the attack at a chic coffee shop in Beijing’s financial district. Fang cuts an imposing, brawny figure, yet speaks quietly, quickly and with an insistent tone that makes it hard to get a word in. He told me about his interest in the lost spirit of China’s anti-imperialist May Fourth Movement: the early 20th-century cultural and political uprising that championed critical thought and innovation, guided by two enlightenment concepts famously personified as “Mr Science” and “Mr Democracy”. “Not many people understand the work we are doing,” he said. “Most Chinese people’s attitudes to science are superstitious and fearful.” Things may be even worse at the elite level, he said, where science is encouraged in the abstract, without a grasp of the scientific method. Regarding scientific and critical thinking, Fang added, “Chinese people need a new enlightenment.”

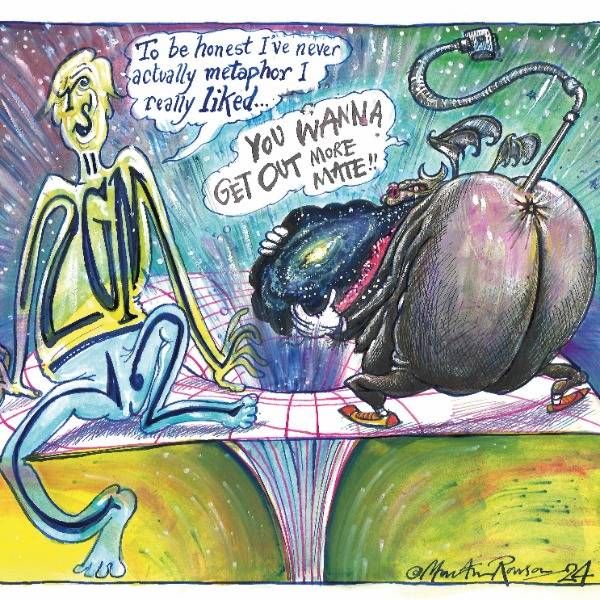

Jia Hepeng, editor of the government-backed magazine Science News Bi-weekly, agreed. At an elite level, he explained: “Science – with a capital ‘S’ – is regarded as a once-and-for-all solution to Chinese problems, and as a result it has enjoyed a higher status than any other discipline in China. Anything that is scientific is equal to good.” An important slogan of the current generation of Chinese leaders is the so-called “scientific view of development”, and the government periodically leads crackdowns against “superstition”. But these have nothing to do with “evidence-based approaches” or the “experimental spirit”, he said. Here is the predicament in today’s China: Mr Science may be good, but independent, critical thinking is bad – or as Fang discovered, even life-threatening. This leaves the science dissenters – the sceptics who understand science not as an ideology, but advocate experimental, evidence-based approaches and dare to criticise malpractice – walking a political tightrope.

In his speech to Peking University graduates professor Wang bravely ventured that “International rankings, such as which country is number one, are not important.” But it’s a message that hasn’t reached China’s bureaucrats leading the push for achievement in science. This publish-or-perish culture has led to unrealistic targets at Chinese universities – and as a predictable consequence, rampant plagiarism. In January, the peer-reviewed international journal Acta Crystallographica Section E announced the retraction of more than 70 papers by Chinese scientists who had falsified data. Three months later, the same publication announced the removal of another 39 articles “as a result of problems with the data sets or incorrect atom assignments”, 37 of which were entirely produced in Chinese universities. The New Jersey-based Centenary College closed its affiliated Chinese business school programme in July after a review “revealed evidence of widespread plagiarism, among other issues, at a level that ordinarily would have resulted in students’ immediate dismissal from the college.” A government study, cited by Nature, found that about one-third of over 6,000 scientists surveyed at six top Chinese institutions had practised “plagiarism, falsification or fabrication”.

But it’s not only the emphasis on quantity that damages scientific quality in China. Publication bias – the tendency to privilege the results of studies that show a significant finding, rather than inconclusive results – is notoriously pervasive. One systematic review of acupuncture studies from 1998, published in Controlled Clinical Trials, found that every single clinical trial originating in China was positive – in other words, no trial published in China had found a treatment to be ineffective. Moreover, a nationalistic and defensive approach to discredited methods keeps superstition alive in the academies and government.

i once sat through an invited lecture at Beijing’s prestigious People’s University, delivered by an bespectacled professor in a white lab coat, which linked the science of genetic modification to crop circles and the teachings of the Vietnamese guru Supreme Master Ching Hai (author of The Dogs in My Life and The Birds in My Life). But perhaps the most controversial example of government-backed pseudoscience is earthquake forecasting – and this is a particular focus for China’s debunkers. (Jia Hepeng, whose magazine is critical of the practice, told me of his shock at finding a display about the country’s achievements in earthquake forecasting at a museum dedicated to that milestone of palaeoanthropological discovery, the Peking Man.)

The practice of earthquake prediction – which can include observation of seismicity patterns and electromagnetic fields, but is also usually characterised by post-hoc analyses of phenomena like anomalous animal behaviour – is largely discredited in scientific circles. One commentary in Science, titled “Earthquakes Cannot Be Predicted”, concluded that it seemed “unwise to invest heavily in monitoring possible [earthquake] precursors”. An advisory body to the Japanese prime minister – Japan had previously been supportive of earthquake prediction research – argued in 1999 that forecasting was not realistic and that research should instead focus on developing new disaster prevention technologies. But nonetheless the practice remains an article of faith for many Chinese scientists and officials, particularly since Chinese seismologists have long claimed that they successfully predicted the 4 February 1975 earthquake in the north-eastern city of Haicheng, and that the subsequent evacuation of the city avoided many injuries and deaths.

Caught up in the fervour of the Cultural Revolution, with its emphasis on mass participation in science (one popular slogan: “the lowliest are the smartest and the most elite are the most foolish”), the Communist Party declared the Haicheng prediction a victory for Maoist ideology and mobilised about 100,000 amateur seismologists and volunteers to work as earthquake forecasters. One sympathetic account from the time describes a volunteer brigade in Shenyang, north-east China, which had someone stationed around the clock to listen for unnatural rumblings in a speaker wired to a microphone placed in an underground tunnel. However, an official Chinese publication 13 years after the quake stated that there were 1,328 deaths and 16,980 injuries from the Haicheng quake (scientists had previously said that “very few” were killed). The main quake was also preceded by an intense series of foreshocks for around 24 hours, likely causing many people to flee spontaneously.

The practice led to many false alarms, continuing up until the 1990s: some 30 inaccurate predictions brought Chinese cities to a standstill between 1996 and 1999 (although the Xinjiang Seismological Bureau claimed a success in predicting an earthquake in Jiashi county in 1997). More memorably, scientists failed to predict the hugely destructive Tangshan earthquake in 1976, which resulted in more than 240,000 deaths. But rather than dampening the fervour for earthquake prediction, the tragedy of the Tangshan quake was instead blamed on the inadequacies of China’s earthquake administration. Officials were singled out for having ignored purported natural indicators of disaster: these apparently included the migration of yellow weasels and unusually large catches of fish. Aftershock, Feng Xiaogang’s recent blockbuster film about the disaster, opens with a huge swarm of dragonflies, presented as a natural omen of the quake. It is clear that such speculations distract from the real deficiencies in disaster prevention and response. For example, it appears likely – although full investigations have been prevented and activists pursuing the case, like Tan Zuoren, have been jailed – that many schools in Sichuan province were built to extremely low standards and that there were many avoidable deaths of children during the May 2008 earthquake.

Whether the issue at hand concerns earthquakes or nutrition or medicine, what we witness in today’s China is the way in which science – upheld since the early 20th century as the cornerstone of Chinese development – is repeatedly stymied by ideology, superstition, bureaucratic thinking and fear of dissent. This is a frightening situation.

As China enters a new phase of economic and geopolitical might – and its model of authoritarian capitalism gains an increasing number of admirers, from developing-world leaders to op-ed writers in the rich world – the country’s attitude towards honest, rational inquiry becomes of crucial importance. China’s approach to critical thinking will help define the country’s response to global scientific challenges, from pandemics to climate change and the environmental crisis. We can only hope that the courageous voices of debunkers like Fang Zhouzi and Fang Xuanchang will continue to be heard.

Editor's update - since this piece went to press, Fang Zhouzi has also been attacked in Beijing, sustaining minor injuries. More information on this on the New Humanist blog.