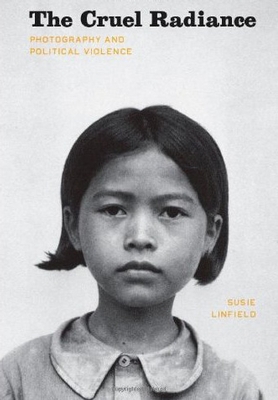

The Cruel Radiance by Susie Linfield (Chicago University Press)

“Who are you who will read these words and study these photographs, and through what cause, by what chance, and for what purpose, and by what right do you qualify to, and what will you do about it?” This confrontational sentence comes from the pen of writer and film critic James Agee, as does the title of Susie Linfield’s timely attempt at a rehabilitation of images of what she terms “political violence”.

“Who are you who will read these words and study these photographs, and through what cause, by what chance, and for what purpose, and by what right do you qualify to, and what will you do about it?” This confrontational sentence comes from the pen of writer and film critic James Agee, as does the title of Susie Linfield’s timely attempt at a rehabilitation of images of what she terms “political violence”.

In invoking Agee as the work’s spiritual antecedent, Linfield stakes her case instantly as one imbued with serious moral purpose. Agee accompanied the singular American photographer Walker Evans to the homes of poor tenant farmers in Hale County, Alabama, in the grip of the Great Depression to complete what was initially a commission for Fortune magazine (but ended up as the seminal book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men). Linfield feels the same appalling discomfort described so vividly by Agee on looking at photographs of people in abject conditions and has surely wrestled with questions like those fired off above. Her clarity of prose and purpose are testament to that self-scrutiny, which has resulted in this book. Linfield’s passionate insistence is that photographs – hard-to-look-at pictures of violence and death – can help us to see, see in the philosophical sense of knowing. So she wants to know why so many people who write about photographs seem not to like them very much. It’s a pertinent question.

Charles Baudelaire, who came of age with the inception of photography, despised it as a mere product of industry. This scepticism was perpetuated by great Weimar critics such as Siegfried Kracauer, who felt photographs could “sweep away dams of memory”, and Walter Benjamin, whose criticism was at least tempered by his dialectician’s mind to recognise their possibilities for liberation. Brecht was perhaps their fiercest opponent, saying in 1931 that photojournalism had “become a terrible weapon against truth”.

Indeed it had. But Linfield, who is an expert guide on this whistlestop tour of photographic criticism that forms the introductory essay, is quick to point out that we no longer live in the same world. Just as the Weimar Republic created the conditions for the kind of photographs it produced (including their highly successful deployment as visible agents of fascism) at the height of the ultimate crisis of modernity, so too are contemporary photographs created by the conditions of this episteme. And those conditions, like the photographs, are not pretty. The terrible photographs of the corpses of Buchenwald were after the fact, a kind of “late” photography, and the post-Shoah desire not to look, not to aestheticise, was a mark of respect and an admission of the unknowability of horror. Today photographs of atrocity reverberate around the world within seconds of the event taking place. To choose not to look is to choose to ignore. People are not so interested in what is happening in Darfur these days. It might be a genocide, like Rwanda, or Bosnia, yet, following the UN’s example, people often find it is best to do nothing, not even to look. Among many insightful comments, Linfield remarks that there is a point at which opposites embrace: “the humanist loathing of atrocity images colludes with the desire of the perpetrators to erase their crimes.”

Linfield’s concomitant investigation is to try to discover “whether photography itself can make the world more livable” and it is this trajectory she follows in the ensuing chapter, “Photojournalism and Human Rights”. Here she ranges widely, taking in photographic evidence of King Leopold’s cruelty in the Congo, official portraits from the infamous Tuol Sleng prison in Cambodia and ending with the so-called “Twitter Revolution” in Iran. Her central point is that “photographs mirror the lacunae at the heart of human rights ideals”; that is, you can’t picture it. But some photographs could perhaps picture what a person looks like without those rights.

The rest of the book is divided – somewhat arbitrarily – into “Places” and “People”. From Lodz Ghetto to Abu Ghraib, by way of Sierra Leone and China, Linfield is at her most fluent when discussing that with which she has a personal connection. This flows naturally from her belief that writing about photographs with emotion and feeling is not the anti-intellectual enterprise that many (female) postmodern critics suggest. She doesn’t labour her point about “fear of frivolity” among female academics, but it’s an astute comment that is worthy of further consideration, not least by female academics.

By the end of the Abu Ghraib chapter, Linfield has found her own threshold: that she does not want to see photographs of executions or of the flailing flesh of suicide bombers. That this is her point of “breakage” is understandable; but as a conclusion it is unsatisfactory, opening her to the charge of (self) censorship, and resulting in the termination of a discussion about what war really – guts and entrails – looks like before it has even begun. Still, everyone has a limit.

In the “People” section, Linfield riffs on three famous photographers, Robert Capa, James Nachtwey and Gilles Peress. She excels at describing the social context that brought about their pictures, though in framing her arguments through the prism of personalities, Linfield risks writing about intention as opposed to photographic aesthetics, though her research is too punctilious to be extinguished by this approach.

Linfield’s great achievement with The Cruel Radiance is more than to shake up the orthodoxy that says “Look away!” It’s a call to arms, an incitement to look closely at the world via the medium of photography, and, implicitly, to do something about it.