I’ll be honest. Discussing gay adoption and condoms with Benedictine monks and spokesmen for Opus Dei is not something I normally find myself doing on a Tuesday evening. But there I was, at the invitation of Alan Palmer of the Central London Humanist Group, who had responded to a post I had written on the New Humanist blog, in which I’d recorded my concerns over the tone of the debate during the Pope’s UK visit. There are crucial disagreements between the Catholic Church and its opponents over issues such as AIDS, gay rights and child abuse, but, I asked, was the opportunity to debate these in danger of being buried beneath the headlines and protest slogans?

I’ll be honest. Discussing gay adoption and condoms with Benedictine monks and spokesmen for Opus Dei is not something I normally find myself doing on a Tuesday evening. But there I was, at the invitation of Alan Palmer of the Central London Humanist Group, who had responded to a post I had written on the New Humanist blog, in which I’d recorded my concerns over the tone of the debate during the Pope’s UK visit. There are crucial disagreements between the Catholic Church and its opponents over issues such as AIDS, gay rights and child abuse, but, I asked, was the opportunity to debate these in danger of being buried beneath the headlines and protest slogans?

In my blog I’d mentioned by way of example the behaviour of sections of the audience at a pre-visit debate at London’s Conway Hall, when the Catholic speakers were frequently drowned out by rowdy heckling. Palmer, the organiser of that debate, read my post and invited me to a smaller discussion between Catholics and humanists, with the aim of discussing some of our key disagreements without the bellicose tone. I agreed.

Which is how a group of 25 of us, evenly balanced between faithful and faithless, came to meet in a room rented from the University of London near Euston. After brief introductions, the three main Catholic speakers – Austen Ivereigh, a journalist and former press secretary to the Archbishop of Westminster, Jack Valero, press officer for Opus Dei, and Fr Christopher Jamison, a Benedictine monk who featured in the BBC series The Monastery, together the founders of Catholic Voices, a group formed to speak up for the Catholic side in the media during the Papal visit – put forward their arguments on gay adoption, condoms and faith schools. The humanists then challenged them in an open discussion. In what felt like a particularly useful exercise, one of the humanists had to sum up the Catholic arguments, and one of the Catholics did the same for the humanist case.

As my first foray into the world of “inter-faith dialogue” (if we extend the definition to include the godless) I thought the meeting had been a good one. As you might expect, there was strong disagreement between the two sides, and I doubt anyone went home with their mind changed on any of the issues. But, while people had expressed strong opinions, the debate was conducted in a manner that meant it could continue over a drink afterwards. Given the way Catholics and humanists were portrayed in some of the press coverage of the Pope’s visit, that’s something you might have thought as likely as West Ham and Milwall fans enjoying a pre-match pint together on derby day. With the religious and non-religious often talking past each other in the public square, it felt constructive for a group to meet and discuss their differences in an amiable fashion. For me, it served as a reminder that you can still get on with someone even if you disagree. This may seem like an obvious point, but it is easily forgotten amid the belligerent tone of the religion debate. And if we can find a way to talk calmly about our disagreements, perhaps it would be possible to find some common ground where we could agree.

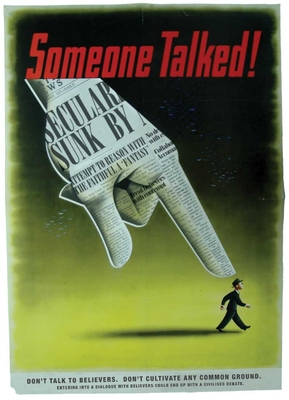

But not everyone agrees that this is the right thing to be doing. Terry Sanderson, President of the National Secular Society, who has previously described inter-faith dialogue as a “fantasy”, was particularly critical of our meeting with Catholic Voices, whom he says he holds in “contempt”. In an article entitled “The Vatican will not be changed by persuasion, it has to be forced”, published on the NSS website, he singled me out for criticism, suggesting I had “entered into talks”, and was “obviously of the opinion that something can be achieved by debating and negotiating with Catholic Voices”. This was, charged Sanderson, “an activity surely worthy of King Canute”, and he concluded by recommending that I “stop trying to reason with an organisation that considers anyone who criticises it to be blasphemers and heretics and join the all-out attack by the ‘aggressive secularists’ that the Pope so fears.”

In suggesting that we had somehow entered into negotiations with Catholicism on behalf of atheism, Sanderson highlights one of the key problems with inter-faith, or inter-communal, dialogue. All too often those engaging in this kind of enterprise have done so with pretentions of representing an entire constituency of people, many of whom would be surprised to learn that someone is claiming to speak on their behalf. New Labour’s response to 9/11 and 7/7 was a classic example of this – desperate to facilitate positive interaction between divided communities, the previous government afforded numerous unrepresentative, and in some cases unsavoury, Islamic groups and self-styled “community leaders” the opportunity to speak as though they represented Muslims everywhere. For the humanists involved, grand ambitions of this kind played no part in our meeting with Catholic Voices. Indeed, in my introductory remarks there I pointed out that I wouldn’t ever claim to speak on behalf of New Humanist’s readers, let alone humanists in general. As for Catholic Voices, while they were set up “to articulate with conviction the Church’s positions on major contentious issues”, they say on their website that they do “not speak officially for the Church”.

But if you’re not representing anybody, you already know what the other side is going to say, and you’re probably not going to change their minds, why bother? Wouldn’t it just be easier to stay at home? My own problem with the debate over the Papal visit had been one of tone, and it’s in this area that I think dialogue has the potential to make a difference.

The idea of “civility” is something that interests sociologist Keith Kahn-Harris, who has been exploring the fractious discourse around Israel and the Palestinian question within the Jewish community in Britain. For the past 18 months he and his wife Deborah, who is a rabbi, have been hosting a series of intra-communal dialogues (he prefers “communal” to “faith”, as it avoids the implication that the process is about a shared belief in a god) around their dining table in which small groups of Jewish leaders and opinion-formers debate how they might disagree about Israel in ways that do not, as so often, in Kahn-Harris’s words, “degenerate into a slanging match”. Guests have come from both ends of the political spectrum – Daily Mail columnist Melanie Phillips and the Guardian’s Jonathan Freedland attended on the same night – and Kahn-Harris hopes the meetings have “helped plant the idea of civility in people’s heads”. (You can read his piece about the civility discussions on the Jewish Chronicle website.)

Why “civility”? “I was looking for a concept that was perhaps less specific than dialogue,” says Kahn-Harris. “Civility suggests a more general way of conducting yourself, with wider implications than something like dialogue. I believe everybody has the right to be as rude as they like, but the question is whether it’s a good idea.” Critically civility is not about agreement, or even negotiation. It is about how we can disagree in such a way that we retain the respect of those we disagree with, and build the possibility of finding common cause on issues beyond our disagreements. Kahn-Harris, who describes himself as an agnostic Jew and is a contributor to New Humanist, believes that the idea of civility could be of use to humanists and secularists. “The so-called New Atheism is often associated with quite vituperative figures,” he says. “I have a lot of admiration for those figures, but the shrill tone doesn’t actually help when it comes to finding common ground. It’s not doing anything politically. It’s just creating more barriers in society in ways which don’t seem to be helping at all.”

Which brings us back to the Pope. When Richard Dawkins, in the pages of this magazine, describes him as “head of the world’s second most evil religion”, or the NSS suggest that “battle lines” have been drawn in the wake of his visit, the media are handed their sound-bites on a plate, but it is not clear what is actually being achieved. Non-believers were rightly outraged by the implication that atheism is somehow synonymous with Nazism, yet Terry Sanderson plundered the same rhetorical toolbox to accuse me, along with the Central London Humanists, of engaging in “appeasement” for even bothering to listen to what Catholic Voices have to say. The implication, of course, is that this represents an unforgivable pardoning of a mortal enemy, and that the only viable alternative is conflict and eventual defeat for one side. The religious and non-religious are divided on many issues, but must debate over these matters really be framed in such adversarial terms?

There is agreement among secularists that change in the Catholic Church must come from within, and there can be no doubt that many moderate Catholics share secularist concerns on condoms, gay rights and child abuse (see the contributions of liberal Catholics Conor Gearty and Tina Beattie to our “An audience with the Pope” feature). If the Pope’s recent pronouncement on condom use was prompted by any kind of pressure, it seems more likely that it was from his own flock rather than his secular opponents. Is it not, therefore, useful to cultivate any common ground we might share with believers? An example of this came in the run-up to Christmas, when former Archbishop of Canterbury Lord Carey launched his “Not Ashamed” campaign, claiming Christians are a persecuted minority in the UK. Joining the secular voices deriding this stunt was that of the eminently sensible Bishop of Croydon, Nick Baines. This suggests that on issues of religious excess, there are believers we can talk to.

The perception of “aggressive atheism” has, rightly or wrongly, taken hold in public discourse and it is something humanists and secularists need to be aware of if we are to influence debate on the range of issues that matter to us. If a bit of civil interaction with religious people could help to achieve this, wouldn’t it be worth it?