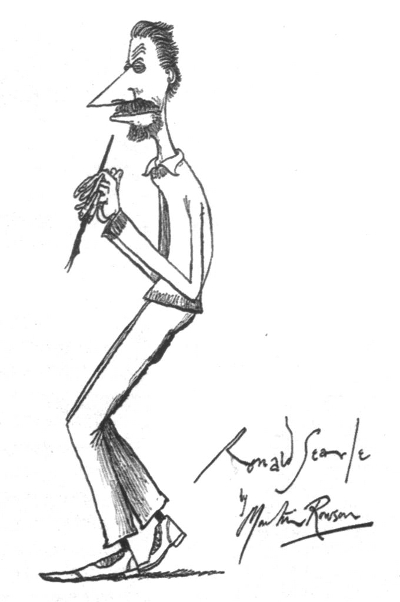

Still, this crass Beeb blunder provides an opportunity to explore an aspect of Searle the headline obituarists have chosen to ignore, and that’s his “line”. On both the BBC4 show and at a talk during the 2010 Cartoon Museum Exhibition to celebrate Searle’s 90th birthday, I had a chance to have a stab (and that’s the appropriate verb) at the way Searle drew. On the second occasion, I was even using some of Searle’s own pens and nibs, including one made out of bamboo (later he actually sent me a box of his own pens), and though it takes a lot of practice and nerves of steel, eventually if you try hard enough you can unveil surprising new truths simply through imitation.

For example, Searle’s scratchy style is hardly in evidence in the first St Trinian’s cartoons, even though these are, apparently, his most important work. It’s only later in the 1950s you can see him begin to use the nib like a cross between a chisel and a stiletto: he bends and twists the tines of the nib to widen and contract the line, stretching into a wisp of gossamer and flattening it into a splodge, but with the point of the pen never leaving the surface of the paper for a second.

This in itself is daring; but what he did next was close to genius: he started to overdraw. That means he started breaking the basic rule of graphic representation, whereby a horizon behind the perpendicular of a tree in the foreground is shown to be occluded by the tree: the line, in other words, breaks the horizon’s line, to maintain the illusion of recreated reality. But not with Searle. I don’t know whether it was deliberate or even conscious, or he just liked the look of it, but once he broke both the line and the rules, his work becomes something almost transcendentally beautiful. As someone once said to me about the way the great Ralph Steadman pulls off the same trick (thanks entirely to Searle), it marks the difference between the controlled, constrained artifice of pornography and the joyous explosion of freedom you find in true art.

Bothering to analyze those spatters of blots – which bedeck the paper like fireworks or champagne bubbles – may seem to be impossibly arcane. I doubt Searle thought too deeply about it himself. But it’s worth teasing out another thread in Searle’s work: how he recorded the torture and deaths of his fellow POWs working on the Burma Railway, and by furtively recreating reality thus brought it under some kind of redemptive control;

how he then took those experiences – and sometimes the actual composition of his Burma drawings – and again recreated horror into (albeit dark) comedy in the St Trinian’s cartoon, achieving further redemption by laughing reality deeper back into its stinking lair. His way with a line then provided the propellant that sent him soaring off into true genius.

how he then took those experiences – and sometimes the actual composition of his Burma drawings – and again recreated horror into (albeit dark) comedy in the St Trinian’s cartoon, achieving further redemption by laughing reality deeper back into its stinking lair. His way with a line then provided the propellant that sent him soaring off into true genius.

And all of that is at least part of the reason why the St Custard’s “skool dog thinking” (right) remains one of the most beautiful British illustrations of the mid-20th Century.