I am a brave man. At least that’s what I’ve been repeatedly told over the last few months. Apparently lots of people are impressed by my courage. These are not people who saw me stand up to bullies as a child or even people who may have witnessed my most recent act of valour – breaking up a fight between two women on the Walworth Road, risking the wrath of other passers-by whose entertainment I was interrupting. No, the people under the impression that I am somehow heroic have come to this conclusion based on the fact that I have written a book.

I am a brave man. At least that’s what I’ve been repeatedly told over the last few months. Apparently lots of people are impressed by my courage. These are not people who saw me stand up to bullies as a child or even people who may have witnessed my most recent act of valour – breaking up a fight between two women on the Walworth Road, risking the wrath of other passers-by whose entertainment I was interrupting. No, the people under the impression that I am somehow heroic have come to this conclusion based on the fact that I have written a book.

My publisher must also be brave. Other publishers liked my book, but declined the opportunity to publish it. One wrote to say that, while she was personally very keen to publish my book, a “number of people” in her company would be “uncomfortable” about it. She then confessed that she really meant “afraid”, not “uncomfortable”.

So what is this terrible tome I have written? At this point, if you haven’t read my book, you might be forgiven for thinking that, to have struck such fear into the heart of Britain’s literary elite, I must have written a pornographically blasphemous account of the life of Muhammad. But I have done no such thing. My book, The Young Atheist’s Handbook, simply tells the story of my personal journey to becoming an atheist.

I was born in Bangladesh but did most of my growing up on a council housing estate in South-East London. My family arrived in the UK in the early 1970s, as part of a large wave of immigrants from Bangladesh, invited over here at a time when the country was prosperous and in need of workers. Yes, we were invited, but this didn’t stop local racists telling us to “fuck off back home” on a regular basis or subjecting us to other forms of humiliation, ranging from being spat at in the street to being beaten up outside our own front doors. I guess it’s a sign of progress that it’s hard for people who never encountered it to believe this kind of open, visceral racism existed. As a child, I felt powerless against it and believed that I was destined to be a second-class citizen in this new home of mine. Perhaps worse than getting abused or beaten up was the humiliation of seeing the adults in our lives similarly defenceless – one friend watched helplessly as a white woman spat in his mother’s face outside the school gates; another was followed home by a gang of thugs, where they smashed down his front door and beat up everyone in his family.

Growing up on a council estate had its drawbacks, but it also had some advantages – there was a genuine sense of community and I remember with fondness how my friends and I were in and out of each other’s homes all the time, how every Bangladeshi adult was an “aunt” or an “uncle” and how much it really did feel as if we were one big extended family. The other thing we all shared was Islam, the religion around which much of our cultural lives revolved, the religion that remains central to the lives of most of my childhood friends, the religion that, ultimately, I came to reject.

The Young Atheist’s Handbook tells the rest of my story, with reflections on philosophy and theology thrown in for good measure. But because I come from a Bangladeshi background, because I was born into and grew up in a Muslim community, people who don’t know me, who haven’t read the book, have leapt to the conclusion that I must somehow be “brave”, and this worries me.

I’m not worried because I think they’re right, or because I might actually be in any danger. I’m worried because there’s something insidious about the idea that I am brave, because at the heart of that suggestion is a very negative view of Islam and Muslims. Perhaps we should all be worried when a major publisher chooses not to publish a book, not because the book was poorly written or because it lacked sales potential (they agreed I was “promotable”), but because people working for the company would rather self-censor than put out ideas that might cause “offence”. Perhaps we should all be worried when powerful people in the media behave as if they have swallowed whole the idea of Muslims as a uniform, intolerant mass, incapable of dealing with the idea of one of their number leaving them.

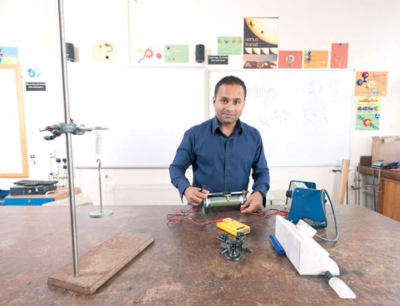

I did not set out to write the book that, to my sheer and utter delight, has now been published. I am a science teacher and my original intention was to write something more like a textbook, a beginner’s guide to ideas from philosophy, theology and science that might be useful to those just starting to come to terms with their lack of belief in a deity. I took my idea along to my literary agent, and she told me it was a nice idea, but unlikely to sell. Before my disappointment had time to sink in, she quickly said something along the lines of “but you’ve got an interesting story, why don’t you try to write something that includes some of that”. So, I went away and rewrote my proposal, combining the material from my original “handbook” with a biographical narrative that, as my agent correctly saw, made for a more readable book.

Changing the book like this also changed my hopes for it. I started off hoping I’d write a book that would prove useful to young people who might struggle to read some of the other texts out there, who might want to read a less sophisticated book before moving on to read the works of great thinkers for themselves. I still want my book to reach young readers in particular because I think they deserve the freedom and guidance to explore the big questions about life for themselves. It seems to me that children are over-exposed to religious ideas and I think atheists and humanists ought to do more to redress the balance. Religion prospers because religious followers indoctrinate the young; if we want atheism and humanism to flourish, we must take action to ensure more children are exposed to the ideas and values we hold dear.

Once I started writing my own story, I wanted more for the book. I wanted to write a book that might appeal not just to children, but to adults who might not pick up a book by Richard Dawkins or Christopher Hitchens or any of the other so-called horsemen of the New Atheism. I wanted to write a book that might resonate with others out there because of the human story it presents, and not be off-putting by having an overly intellectual or academic tone. I wanted to write a book that showed that “ordinary” people can lead happy godless lives, that atheism is not the preserve of an intellectual elite.

I developed another hope for my book which I hesitate to raise here because I fear that some readers will simply stop reading. This hope, as I explained in a piece for the Guardian’s Comment Is Free website, is that my work will go some way to encouraging atheist and humanist movements to recognise that they need to do more for people from backgrounds like mine. To be a true “community”, atheism needs to move away from its white, male image and encourage black and Asian people to join.

Despite my careful attempts to clarify that I was not accusing anyone of being racist, many readers of that piece responded with a venom I was not expecting. Here are just a few examples:

“Who is stopping black and Asian people from being atheists? What is this ‘community’ (bleurgh) of which you speak? Or are you just upset you don’t get invited to all the parties Dawkins and Hitchens do?”

“I don’t belong to any ‘movement’ or ‘community’ and I don’t have a ‘leadership’. I just don’t have a God. What a bloody bonkers article.”

“This is nonsensical. Atheism has, or should have no Church, and doesn’t need missionaries to persuade and cajole the religious into changing their beliefs.”

“Why should any supposed movement based on free choice, the absence of superstitious dogma, and against the priviliging [sic] of certain sections of society over others begin to make special efforts towards certain sections of people over others?”

There were two constant themes that emerged from commenters such as these – first, a lack of empathy for people from backgrounds different from their own, and second, an assertion that there’s no such thing as an “atheist community”. The fact that there is a “Global Atheist Convention” about to take place as I write this, and that there are numerous rationalist and humanist associations around the world, is enough to disprove those who claim that atheist communities do not exist. But the problem of people refusing to acknowledge that it might be more difficult for people from certain backgrounds to be openly atheist is more difficult to address.

Some atheists seem unaware of the fact that religious customs and traditions can be central to the identity of entire communities of people, and individuals who don’t believe in God may still want to carry on those traditions and customs because they feel some kind of moral duty to maintain them. So, for example, someone who identifies themselves as Jewish may in fact be an atheist in an intellectual sense while at the same time insisting on eating only kosher food or only marrying someone who is Jewish. I have heard people claim that some Jews, despite not really believing in a God, do these things because if they do not, they feel they will be guilty of “finishing what Hitler started”.

Family and community play an important role in the lives of many, if not most, people. To be part of a group, we must share values. It may be more important to a person to remain part of a group than to confess his or her atheism. After all, as Muslim friends have pointed out to me, what’s the point of rocking the boat, of upsetting your mum? For many non-believers, secrecy and pretence are the only options they feel they have, even as adults, so that they can be good children to their parents. A friend of mine tells me that he “protects” his mother from his “true opinions”; I don’t blame him for it one bit, as I have no doubt I would have “protected” my mother in the same way.

I know a number of “ex-Muslim atheists”. We gather in pubs, raise glasses of alcohol in celebration of our godlessness and order the sausages and mash to demonstrate we don’t believe there’s any good reason (apart from vegetarianism) not to eat pork. But I am one of a small minority of “ex-Muslims” who is openly atheist in my day-to-day life. Being a good little science teacher, I’m not just going to provide you with anecdotal evidence for the fact that it is more difficult for some people to be openly atheist than it is for others. Instead, I’ll quote from a study, “Losing Faith Without Losing Face”, from 2011, by Suzanne Brink and Nicholas Gibson of the University of Cambridge. They carried out research into the experiences of people who described themselves as “ex-Muslims” and found: “There are cases in which people have ceased to believe in their religion yet continue to pretend to believe in that religion. The reasons behind this decision are generally social in nature. It may be that they are afraid of getting hurt when stating their disbelief openly, or it may be that they do not see enough merit in disclosing their newly found disbelief to justify hurting the people whom they love. They prefer remaining a secret disaffiliate… of those making any mention of disaffiliation, around one-third of all narratives included statements to the effect that the authors considered it a necessity to keep their deconversion a secret.”

So why am I so open about my atheism? Is it because, as some seem to think, I am brave? No. The simple reason why I’m open about my atheism, when others like me are not, is because both my parents are dead. My mother died when I was 13 and my father did not play a large part in my upbringing following her death. It seems perverse to say it, but I may have been lucky in having had little in the way of parenting as a teenager. I suspect that, had my mother lived, I would not be so open or outspoken about my atheism. I loved my mother deeply, and, had I thought it was something she wanted, I am sure I would have made more of an effort to be a Good Muslim, or at least kept up more of a pretence of being one. But with my mother dead and a deep lack of respect for my father, I was relieved of the reason why many atheists I know, particularly ex-Muslim ones, continue to pretend to be religious – I no longer had a desire to “protect” my parents from being upset, or from being “shamed”. I was freed of the pressure to believe what my parents believe. But this is a pressure that most people, especially, I would suggest, from communities such as the one I came from, have to live with well into adulthood.

For many Muslims living in the west, the events of 11 September 2001 and the resulting Islamophobia have, understandably, forced them to identify more strongly as Muslims. For me, one of the saddest outcomes of this atrocity is that the actions of a tiny, tiny minority of Islamists have forced a wedge between Muslims and the rest of the world that they did not ask for, creating a barrier that only compassion and empathy will break down.

Whilst I empathise with many Muslims and why they might choose to assert this aspect of their identity, it is one that I have explicitly rejected. Not just because I don’t believe in Allah but because I feel that it is my duty to assert my own identity as an atheist – I feel it’s important for people like me to be “out” because there are not enough people from my background, that is, a Muslim background, who are willing to be open and honest about their lack of belief in God, and this makes it difficult for young people from these communities to be who they truly want to be. The sad truth is that I am a rare breed – a public “ex-Muslim” – and one of the reasons why I am glad I have written my book is that it will let others, who keep their lack of faith a secret, know that they are not alone.

I hope I am not being over-dramatic or self-aggrandising – since first talking about my atheism in public, I have been contacted by numerous people with emails like this one:

“I am of Indian origin and Muslim by birth. I was expected to learn about Islam, learn the Qur’an, pray and conform to all of the religion’s beliefs and values. I have always questioned the religion but was afraid to challenge due to the fear of rejection and possibly even being disowned. I am living a life full of lies. I lie to my parents and my siblings about my non-existent belief, I lie that I fast, that I pray and that I am trying to bring up my daughter with Islamic values. I am so tired and frustrated of having to hide this massive truth from my family and I just wish I had the courage to deal with it.

"I just wanted to say, thank you for doing what you are doing because I am sure it will give strength to lots of Muslims out there who are in similar situations. Being a Muslim female, I feel even less empowered to make my beliefs known. All I can do is ensure that my daughter never has to live the same life of fear that I had to, and empower her with the ability to challenge and make decisions for herself. I can defend her – she is my daughter.”

Messages like this make me sure that I have done something useful in writing my book and make me glad that my own siblings, particularly my sister, have been able to live their lives free of religion and make their own decisions about who they want to be and how they want to live.

I am not brave in the way some might think me brave. If there’s anything courageous I have done in writing my book, it is to put forward a deeply personal story, exposing myself in a way that will inevitably change my relationships with people who already know me and affect how people judge me in the future. I have no doubt that some of the Muslims I grew up with will be disappointed by my book, or made to feel uncomfortable by it. But I hope that most will simply shrug and think, “I knew that about him anyway.” And who knows, perhaps a few of them might even be proud of me for it, pleased that “one of them” has had a book published in a world where too few of their stories are told.

The Young Atheist's Handbook: Lessons for Living a Good Life Without God will be published in July by Biteback.

Hear Alom Shaha talking about his life and book to Caspar Melville (from the PodAcademy)