In the North Eastern US, hurricanes and tropical storms are rare, but I’ve experienced a few: Gloria flattened an old tree in my parent’s yard when I was an infant, leading to a notorious argument between my father and my uncle over who got to use the chainsaw to hack up its trunk. Bob forced us to evacuate to a local high school, where we ate peanut butter sandwiches and played Guess Who until the bridge connecting our peninsula to the mainland was passable again. Last year, a dear friend of mine was married at an old Quaker retreat as Irene approached. I drove through the worst of the storm as we, addled from the sort of wedding reception appropriate for the night before the world ends, evacuated to safer ground. Hours later, we strolled around town and went for coffee. And I was in Tampa for Isaac this August, which, as far as Florida hurricane experiences go, was a disappointment.

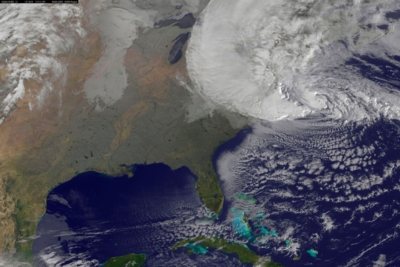

North Eastern hurricanes were with few exceptions all bark and no bite as far as the region’s denziens were concerned. Until Sandy, of course. While evaluating the coverage of Sandy's build-up, those of us in the path of the storm attempted to discern the tell-tale signs of familiar media exaggeration. Meteorologists, funneled through a media-driven game of telephone, would hype the storm into the Book of Revelations. In fact, just weeks after Charlie Brooker used “Snowmageddon” mockingly to describe a UK bout of weather hysteria, We unironically named a major 2010 blizzard just that after it dumped as much as 35 inches of snow in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. This popularized a pattern: there's SnOMG, Snowzilla, Snowpocalypse, and, my favorite, Kaisersnoze. Now, it seems every storm is imbued with a supernaturally inspired portmanteau.

That's not too surprising. The apocalypse carries a certain sort of appeal. Preparing for a disaster, and the possibility of being one of the lucky few to survive, is exciting, after all. We'd never have had zombie movies without that thrill. Likewise, Sunday, for many in the North East, was a mad dash to crowded grocery stores as if everyone was preparing to hole up in their own nuclear bunkers. In the lead-up to a big storm, “This is a big one” carries an excited tone to the voice. While the media hype bears at least partial responsibility for providing us with a ritual pre-storm panic, the rest of us are also guilty of finding the whole thing thrilling.

After expecting – no, demanding – that the weather hype be appeased with nothing short of the actual End Of Time, we’d sigh and wonder “is that it?” as we tried to figure out to do with the emergency water and canned goods we’d grabbed off the shelves. New York City largely responded to 2011’s Irene – a storm that overall caused $4.3 billion in insured losses, cut power to 4 million, and killed 18 people total – with a shrug. The city was a near-miss for the worst of the damage. We shut down the entire subway system for that? Of course, now, New Yorkers are wondering when we'll see those trains moving again. I refuse to imagine weeks without train service, despite reports that indicate I'll have to adjust to just that reality upon my return home.

New Yorkers are like cyborgs, we depend on our machinery to live. The city itself, a series of islands essentially, relies on a network of tunnels, bridges, and trains to run. So shutting the entire transportation system – buses, subway, trains, ferries – down and telling New Yorkers to stay put is like inducing a coma in the entire population. For Sandy, of course, it was the right call. All seven tunnels that take subway trains under the East River are flooded, power won’t be restored for days (including to a huge chunk of lower Manhattan currently darkening a portion of the city’s night-time skyline), and residents have been made homeless, trapped away from their homes, evacuated from hospitals, or worse: 22 deaths (and counting) have been reported so far in New York City alone, with at least 39 dead in eight states. Meanwhile, damage estimates are already topping $20 billion (much more than Irene, but a lot less than, say, Katrina). JFK Airport will be at least partially running on Wednesday, with LaGuardia Airport (where I’m still technically scheduled to fly into Friday evening) down for the count due to severe damage for an undetermined amount of time. And, despite a 2011 report predicting exactly this sort of devastating damage to the system, we don’t know when we’re going to get our subways running again. The limited bus services and crowded taxis currently shuttling residents, tourists and anyone else stuck in the city where they need to go won’t keep New York running the way it runs. And in New Jersey the damage is simply devastating. We’re all still digging out, assessing the damage and waiting for a return to almost-normal.

Sandy could very well curtail the reading of the tea leaves the next time we’re told to expect the Apocalypse by the local TV weatherman: this time, they were right. It's a classic “boy who cried wolf” scenario, but this time it looks like we listened – like we were really going to resist the thrill of impending doom, anyway. We were told Sandy was an extraordinary weather event, and it was. But now the next storm will be compared to its Sandy-like potential, and we'll prepare diligently for it once again. But if they’re wrong, it’s back to our old ways, throwing some masking tape on the windows just in case and assuming the weathermen are, as usual, setting us up for an anticlimax.

That persistent scepticism of media “hype” of weather events has a certain validity. Watch coverage of any promise of weather drama, and see TV news trot out every map, every simile, every dystopian image in their stash to keep viewers glued to their televisions, making possible disasters their own version of the Super Bowl. But that hype has another use, as weather drama scepticism contains within it an insistence that we create meaning out of the movement of the clouds, when, of course, that’s exactly how we ended up telling origin stories to each other around campfires in the first place.

There’s a certain weird pride here in outsmarting the weathermen, in preparing exactly the right amount for a highly variable, potentially dangerous natural occurrence. It’s a guessing game. If you over-prepare, you were taken in by the media, feeding their ratings and ad dollars by buying into their breathless coverage. If you under-prepare, you’re stupid. It betrays a bizarre misunderstanding of what meteorology can and can't tell us about potentially disastrous storm, and one that our weather experts are too often guilty of indulging. In as much as meteorology depends on the caution of the scientific process, we should be much more inclined to trust its expertise. Instead, we're out to win against it.

Being right rings as something of a hollow victory after Sandy, however. I’m sure there will be plenty of lessons learned from Sandy, but here’s one I’m hoping for: earlier this summer in Florida, I waited Isaac's approach and, like everyone else, watched the news. Hurricanes are a season, not a sensation, in Florida, and it showed in the ways in which the weathermen discussed the storm. They presented data, discussed probabilities, urged caution, and otherwise talked to their viewers as if they were responsible adults. The viewership in the state knows their storms, and the more serious coverage (while not immune to the drama-creating tendancies of TV news) demonstrated a different possibility: trust of expertise.

Talking heads with elaborate marching orders for surviving a flood are deserving of our scrutiny. But it would be nice to think that Sandy could provide a means for transforming our adversarial relationship with the forecasters into something more trusting, if only more of our experts could just learn to act like experts.