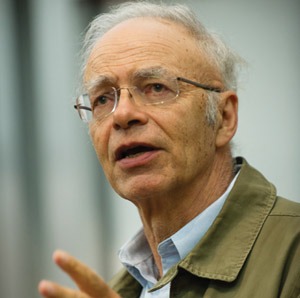

For a professional philosopher, Nigel Warburton is unreasonably youthful and radically comprehensible. Relaxed, unaffected and playful, he gives you the wonderful feeling that his arguments are partly yours because he has enlisted you in their construction. The secret of the trick is the meshing of two roles; those of teacher and thinker, a conflation carried out with unusual ease. But of course, this is no accident. In fact, you could call it a deliberate harmonisation of function and message: Nigel believes philosophy is a subject which contains issues that are relevant to everyone, but in order to achieve this level of access people must be able to discuss those issues in clear logical steps.

The image of philosophy as a removed, disengaged discipline is one that Nigel lives to subvert. "The popular view is that philosophers sit in ivory towers and split hairs. Philosophers actually want you to challenge their basic assumptions, I certainly want people to come back at me and challenge me," he says. So don't be afraid to ask this particular philosopher simple, obvious questions except, perhaps, why he is so young. What, then, according to him, is philosophy's main purpose? The key lies in the engagement in rational, critical debate, and in this process, the furnishing of mental tools to unpack arguments and test the quality of any line of reasoning. "Reasoning, and what makes a good argument, is what philosophy has to offer to the wider world," he says. This fits neatly into the way Nigel defines his own role as a philosopher: "I want to offer clear introductions to philosophy because introductions people's first contact with the area of thought have the most profound effect on people."

Nigel's career is a testament to his idea of philosophy as an educational, outwardly reaching endeavour: Philosophy: The Basics and Philosophy: The Classics are clear and broad introductions to philosophy for the uninitiated, and Thinking from A to Z is a comprehensive guide to understanding the mechanics of rational argument. At the Open University where Nigel teaches, philosophical debate is vigorous and lively: "With online conferencing facilities, you can have people scattered across different parts of the country all arguing with each other. The university thrives on this kind of debate."

Although happy to admit he is working to make philosophy a more popular discipline, Nigel is surprisingly reluctant to endorse the kind of philosophical writing that has appeared in several widely selling novels. "These books are popular because they are unchallenging. They present philosophy as the practice of visiting a museum of ideas and feeling a sense of awe, or alternatively using philosophy as a means of personal therapy. There is certainly a place for 'fun philosophy' but it has to be done in such a way that enables people to think philosophically. Stephen Law's book The Philosophy Files is aimed at children but I think that it does promote the rigour of thinking that anyone can enjoy and benefit from."

The fact that powerful public voices do not always have the qualification of sophisticated insight into the subject of their discussions is a major concern for Nigel. "I'm against truth by authority, and by implication the figure of the universal expert people are often overawed by famous figures who speak on topics that they have no expertise in. Why should we listen to Einstein on the structure of society?" Religious leaders are clearly an example of the same phenomenon. "They do have a place in public debate as they represent a large percentage of the population, but they certainly shouldn't be given particular prominence on ethical committees." What is more, there is clearly a great deal in religious arguments on ethics that Nigel sees as highly presumptuous. "Religious arguments tend to start from the dubious premise that there is a benevolent God, and these arguments only make sense if you accept that premise." The role of the British Humanist Association, he says, is particularly important because it provides a forum, allowing people to deal honestly with their atheism and agnosticism.

In fact, Nigel argues that philosophers should be promoted to play a larger role in any public debate. "Philosophers are engaged in argument and critical reasoning every day, regularly looking at a variety of positions and deciding on the most convincing. Furthermore, when philosophers put their argument in a strong form they are looking for a strong challenge as much as confirmation that they are right."

For Nigel it is important that the public are able to see the kind of assumptions and reasoning errors that are hidden away in statements from both politicians and priests. "Tony Blair could play the religion card at this election, not very wise right now but I do see that things could move in the direction of the US in the next few years." Particularly in the sphere of secondary education, Nigel stresses the importance of meeting Creationist arguments point by point, and this is one area where humanists can apply their values to pivotal effect. This is particualrly important as Creationist websites can be accessed from anywhere in the world. One obstacle to the dissemination of apparatus for clear, critical thinking is the media. The Humanist Philosophers' Group, of which Nigel is a founding member, is a vital mouthpiece and promoter of humanist thinking particularly towards the media. Recently he has helped compile and edit a pamphlet on paternalism in collaboration with the group. "We are examining two of the main arguments against paternalism the 'Best Judge' argument which says that the individual is the best judge of his or her interests, and the 'Autonomy Argument' which stresses the intrinsic value of being authors of our own lives. The aim of the pamphlet is to facilitate debate, not to take a particular stance. I see this as particularly important in a world where people are advancing paternalistic policies without examining the arguments which underpin the decision to intervene. Either that, or they completely reject paternalism as a threat to personal freedom when there are cases such as paternalism towards children when it is clearly desirable."

Nigel's insight into the nuts and bolts of critical reasoning has been put into practice in his consideration of the British Medical Association's position concerning boxing. "I wanted them to move away from their increasingly paternalistic stance over boxing. My position on this issue is that I believe risk-taking is an important aspect of our choice to be what we are. Boxers are consenting participants, and the nature of their profession means that they have to be very committed and determined you don't just fall into it. It might be better simply to educate boxers on the physical risks involved." Nigel argued that the ethical presumptions underlying the BMA's position were not informed by pure medical fact, but by a particular kind of morality. "The BMA's policy on boxing can be attributed to legal moralism rather than medical expediency. The ethical standpoint they are now taking is that the sport involves an attempt to harm. But this is a characteristic of many activities. What is at play here is paternalism under the guise of medically informed argument."

So is Nigel an all-out campaigner against paternalism? He answers: "Of course there are situations where autonomy is not the highest value, such as in the case of a famine, so we can say that in every situation all the arguments have to be laid bare in order to come to the best decision." Moreover, Nigel indicates that there are plenty more debates which need excavating, a need for the cogs of analysis and careful logical thought to be set in motion. "The Humanist Philosophers' Group's next pamphlet concerns religious schools, and we aim to unpack the various issues in that area.

"We do not aim at a complete consensus on philosophical topics, we want the freedom to present arguments from a non-religious point-of-view in an impartial way. Of course these must be debates about present-day issues which have a strong moral and political dimension to them."

The combination of engagement and intellectual curiosity has led Nigel towards areas of debate virtually untouched by critical thinkers or specialists on ethics. Research into photography, aesthetics and the media has furnished him with material for a consideration of the ethics of photojournalism. "I started thinking about the way photography allows us to remove the viewing privileges that original works of art have traditionally had. This led me to think about how far photographic images ever reproduce an 'original', whether there is still any role for documentary photography in a world where images are almost inevitably manipulated before being published. In this context a code of ethics for photojournalists is surely something we should think about." Could this be a message about the great potential for truth-showing inherent in photography? Nigel is quick to put the other side of the debate. "In a sense, photographs have always manipulated what they are attempting to re-present. I think that the really interesting part of this debate lies somewhere between a conception of photography as giving you a slice of reality and what some now call the post-photographic era."

The fact that Nigel Warburton sees philosophy as a tool for anyone to use, a discipline that deals with tangible issues that affect everyone is nothing less than inspiring. He is, however, well aware that people can put the tool to work at the wrong kind of job, and at this point he makes a dash more for a watch tower than an ivory tower and explains amiably: "We have to guard against confusion about the meanings of 'philosophy'. When people say 'my philosophy is...' they often mean 'my bigoted view is...' The same word doesn't always mean the same thing." And, with a grin, Nigel adds: "The Pope even said that he was a humanist once."