In the years running up to this moment I had spent a lot of time ruminating about religion and how it operates. I had had many conversations with theists in which I tried to understand how they could believe what they believed with such surety; and my provisional conclusion was that the essential elements of their religious experiences were so profound and impressive (far more so than those I had experienced myself) that they were inclined – nay, compelled – to accept them as true and incorporate them into their Big Picture.

That they would do so is natural and understandable, even, in a way, sensible. After all, to not do so would entail troubling internal dissonance and feel like a denial/betrayal of those experiences. Or, to put it another way, their choice boils down to either rejecting their own, most profound and gratifying feelings, and therefore accepting a harsher reality and the psychologically-costly possibility that they shouldn’t trust any of their others either; or, incorporating them into a potentially unifying world-view in which most of their actions, verbalised thoughts and morality cohere in a way that feels satisfying and generally seems to "make sense". Or (allow me one more comparison) it’s like being given, for free – in this world so uncertain to the soul – some foundation stones that seem undoubtedly dependable – of the highest provenance indeed – and then deciding not to use them. Nobody would do that without good cause, especially when their immediate society and forbears provide reassuring examples of apparent success in the endeavour.

So begins to arise, to pursue the construction analogy, a superstructure of spiritual, as well as more practical, beliefs built upon some of, or perhaps even exclusively, those foundation stones. Of course the architect-builder’s own character and pre-existing outlook influences the choice of pillars and beams, but whatever is chosen must also work in sympathy with the foundations – else the building will be inherently unstable and them to liable to psychic rifts or even the homelessness of a full-on existential crisis.

As to the walls – and I’ll concede I’m stretching the analogy now – it’s like they adapt facts, and their own experiences, to fit into the framework. So a raw, but virtually unavoidable, building material like the Fact of Death gets transformed into something more in keeping with the grand design: this life is only a staging post and part of a bigger plan for us. That worked brick now looks a lot less out of place when they’re staring at the walls during dark nights of the soul.

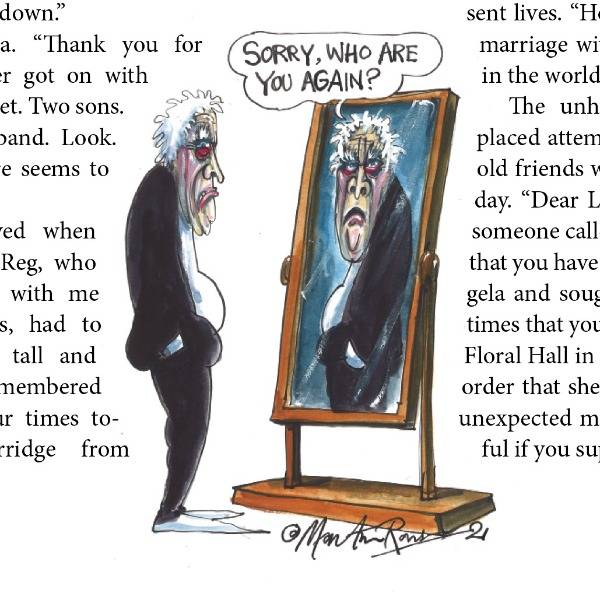

The above understanding of how religion could operate – in myself at least, were I a theist – became the mirror in which I suddenly recognised how I had undergone a strikingly similar process myself, only with my depressive "revelations" and experiences substituted for the more conventional religious ones. In this parallel my substitute foundation stones included the primal elements of depression, for example: feeling my life (indeed everything) was meaninglessness; knowing that my situation was hopeless; feeling unlovable and worthless; knowing that nothing could make me feel like my intact self again. (In passing I acknowledge that there is some blurring between what are core beliefs about oneself and those that are more purely existential in nature.)

I think I need to stress, for understandably sceptical readers, how emotionally impressive these feelings were – like religious ones, I contend – so here I’ve tired to put into words my depressive experience of feeling, as well as merely intellectually knowing, the meaninglessness of the universe:

Everything becomes stained, tainted, imbued with the understanding that it all adds up to nothing. Meaning had been emptied out, as if reality itself is mourning its own state of death. Existence is on a barren, windless, infinite plain; lonely stillness. In the pale dying light bustle looks like staying busy just for the sake of it, humour like cheerful ignorance, hope like childish naiveté.

Other people don’t understand. The truth of these things has not been revealed to them. But I have been granted this terrible revelation and I should not put it aside.

So, like those other believers with the more comforting revelations, I took mine as truth and built upon them. The house I built very likely wasn’t as sound, nor comfortable, nor large, nor as amenable to development as theirs, but I could still construct using a similar approach. As an example, one of the rising pillars of my superstructure was a belief that it’s not worth trying too hard for anything (since it’s all pointless, and you’ll remain unhappy anyway). Another is that relationships are not to be depended upon (since my true, unlikeable character could come to light at any moment).

Bleak as all this may sound, recognising that my revelations were akin to the revelations of theists – revelations which I distrusted – has allowed me to more readily put my own into helpful perspective: they’re not to be trusted either. Yes, though they may (almost coincidentally) align better with the post-Enlightenment facts they remain, despite their impressiveness, still just feelings at bottom. With this new perspective it’s easier to shrink, for example, the overwhelming feeling that my life in the universe is pointless from something I’d taken (apologies) as gospel (and made essential to my whole approach) down to a mere perspective; one that’s no more provable or unprovable than a belief that it really does matter what I do.

When I put it like that it may sound stupidly obvious but – excuse the truism – the hardest assumptions to question are the ones we don’t even know we’ve made; and besides, it’s the further and deeper understanding I believe this has led me to that’s proving even more illuminating. This I come to from reflecting not just about the how (by which I mean my internal process, the construction approach I’d used, the parallels with theism) but also about the why.

By the "why" I mean what were the reasons for my going about constructing a belief system in that way in the first place. Why had I found my experiences so convincing and compelling? So overwhelming? I was reminded of mania and schizophrenia.

In both conditions the sufferer’s perception of reality gets distorted and merged with his beliefs and feelings to such a degree that it becomes dangerously divorced from "real" reality. We all utilise a similar process at times I believe, only not, of course, to the extent that it becomes pathological. What’s especially telling, I think, is that, whilst both share an extreme alteration of their perception of both reality and themselves, mania is often euphoric whereas, in contrast, paranoid schizophrenia is on the outer limits of human misery. Just like – although I’m sure you’re ahead of me now – religious and depressive experiences can be.

The similarities suggest a re-conception: should we move to considering all of the above as members of the same family of intense feelings-led, distorted-perception mental health conditions? Or at least that manic, schizophrenic, depressed and religious individuals share certain personality traits and neurological characteristics (and/or abnormalities), and that it’s the various degrees of them - plus some more specific factors – that determine the final manifestation of their "pathology"? Now, I’m sure the field of psychology is well ahead of me here, but I found it helpful to attempt my own list of commonalities:

• A tendency for their feelings and thoughts to become excessively merged/jumbled/confused – one might say "alloyed" - with their experiences.

• Very little impulse to check that those feelings and thoughts align with the facts and…

• …a lack of ability to do this even if the impulse arises, or it would be useful.

• A strong tendency to "filter" (or warp) reality/events/social interactions/facts through the lens of what they happen to be feeling already at the time and…

• …a diminished ability to recognise when they’re doing that. Also, maybe a reluctance to do so, since reality can feel exhilaratingly ‘amped up’ or hyper-real during these states (mania being the obvious example).

• Become more easily overwhelmed by their feelings (and/or experience stronger emotions), which then makes it even harder for them to think rationally, or clearly, or with balance and so even more likely to give in to their …

• tendency to give credence to those strong feelings (thoughts too), and to also…

• experience them as ‘revelations’ from an external "force".

• A tendency towards black-and-white thinking.

• Have existential concerns. (This obviously applies more to the religious and depressed.)

When I lay it out so bare like that is it any wonder people like me – people who have been practically manufactured "religion ready" – end up believing some bonkers things? Militant atheists take note! (Whilst I imagine they’re listening, I’ll also say that I think don’t think there’s anything, per se, contemptible about this; we just make a very understandable, very human mistake. Of course, they’re entitled not to like it.) I think it also shows how easily our approach can become a trap: we lose the so-valuable perspective on ourselves, and reality itself. In fact, I’d put it that we effectively end up in a different, self-perpetuating reality – one that may be joyous or miserable, luckily deluded or unfortunately all-too-accurate about the worst bits.

I’ll conclude firstly with an acknowledgement that all of the above remains my perspective about perspective. (Given the context making any claim to truth would be akin to throwing same claim to the lions.)

And lastly a hopeful thought: if I’ve learnt anything it’s that increasing my perspective about perspective seems to promise a pathway to self-transcendence. With that in mind, I’ll continue to discuss these matters with all reflective people – believers or not – and I believe I shall take a course in mindfulness.