This article is from the Spring 2014 issue of New Humanist magazine. You can subscribe here.

Politicians have lost faith in their ability to change the world, while the middle classes – once the driving force of reform in liberal democratic societies – cling to a dark and apocalyptic vision of the future. In fact, the only future they can imagine is one in which the planet dies; the kind of scenario evoked in Cormac McCarthy’s best-selling 2006 novel The Road, in which a father and son make their way through a landscape where life has been all but destroyed. This is the conservatism of our age, and the sceptical-minded, rational readers of New Humanist deserve their share of the blame.

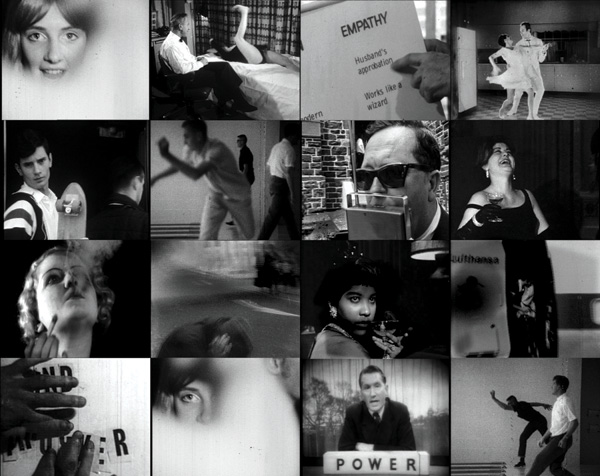

At least, that’s what Adam Curtis seemed to be saying when I first contacted him late last year. I find Curtis’s films fascinating, and occasionally fustrating: his documentaries, which he has been making for the BBC since the early 1990s, combine serious histories of ideas with a populist touch, a rarity in today’s mass media. Films such as The Century of the Self (2002), which tracked how Freud’s ideas about the unconscious were adopted by the advertising industry, or The Power of Nightmares (2004), which argued that the threat of Islamist terror had been exaggerated by US elites, make bold polemical arguments, mixing archive footage and original interviews with Curtis’s distinctive narration: an authoritative “BBC English” voice that recalls an earlier age of TV documentary.

For that, some commentators hate them, dismissing his work as “conspiracy theories with pzazz” or “faux-brow documentaries [that] rely on image and music to state their case rather than rational argument”, as the historian and New Statesman writer Guy Walters has done. But many others love them: his films, which have appeared at intervals of three or four years since the early ’90s, are given prime-time slots on BBC2; online, they have gained a global cult following, while his blog is one of the most visited pages on the BBC website.

So what’s the truth? And is Curtis right about our current failure of imagination? I went to meet him to find out. Rather than go for the conventional interview, I thought I’d take him on a walk instead.

***

Waiting for Curtis to arrive, in front of the ticket barriers at Abbey Wood station one morning in early January, I spot the former Sun editor Kelvin Mackenzie walking past. It’s unexpected: Abbey Wood, in suburban south-east London, is miles away from the media haunts of Westminster or the West End – and Mackenzie’s eyes catch my surprised look for a second before they flick back to anonymity. It’s a coincidence, in fact, that wouldn’t be out of place in one of Curtis’s films, and a voiceover pops into my head – what did the former Sun editor have to do with . . . ? – before it’s interrupted by the arrival of the director himself, dressed in a long dark winter coat and carrying a leather briefcase. “Where do you want to go?” he says.

We’ve come to Abbey Wood because it’s next to the Thamesmead estate: a vast modernist housing development built from the late 1960s by the now defunct Greater London Council. Intended to be a “working-class Barbican” – the brutalist concrete tower blocks of Thamesmead mirror its more famous counterpart in the City of London – it has instead become a byword for urban decay. The walkways and underpasses, many of which have now been demolished, were immortalised as the backdrop to Stanley Kubrick’s film of A Clockwork Orange, while the neighbourhood makes headlines these days as “the fraud capital of Britain”, a reference to the “Nigerian criminal gangs” who supposedly now inhabit Thamesmead.

All this is a far cry from the optimism with which Thamesmead was opened 40 years ago: as Douglas Murphy writes in this issue of New Humanist, the idea that bold new architecture could help alleviate poverty and plan healthy, happy communities is now dismissed as wildly utopian. And for Curtis, this is part of a much wider mood, in which “the idea that we could create worlds that have never existed before” has been abandoned. “I find it deeply depressing,” he later tells me, “because it is so limiting. It’s like living in this horrible little village where nothing is ever going to change and everyone’s going to gossip about each other until kingdom come.”

From Abbey Wood station, we climb the hill – site of a ruined medieval abbey – that overlooks Thamesmead, and look down on the estate: although much of the development has been replaced by more conventional homes, the concrete low-rise and high-rise blocks are what draw the eye as we look north, towards the river Thames. They’re like the last outpost of a wave of 20th-century progressivism; a movement that many leading lights of the Rationalist Association (New Humanist’s publisher), such as the author HG Wells, would have seen themselves as part of.

“You’re right,” Curtis says. “They wanted to take rational ideas and use them as an inspiration to cut through the mist and the fog of conservatism to make the world a better place. Utopian thinking was a kind of kick-start for that.”

If that spirit is lacking now, it’s something Curtis, who was born in 1955, blames on his own generation. “I have a theory that the baby boomers were the first great individualist libertarians of our time, and now they’re facing their own death. If you live inside your own skull as an individualist, the one thing you can’t imagine is that you are going to die. So you project it onto the world.” To him, our response so far to the threat of climate change has encapsulated this attitude. “Rather than using it to reallocate resources, to build new technologies, all we got from the middle classes was a wave of dark, apocalyptic thoughts. A wasted opportunity.”

It’s not just films like The Road that Curtis sees as evidence of this gloominess that pervades our culture: today’s politicians have been emasculated by this failure of imagination, surrounded by advisers and experts who display “Gradgrind-view utilitarianism”. Politicians are “like Rapunzel in the tower, kept there dessicated and dry by these horrible wonks”, while the idea that “all politicians are corrupt, self-serving” – something Curtis describes as “deeply reactionary propaganda” – is ubiquitous.

He’s right that cynicism about politicians is widespread: just look at the response to the comedian Russell Brand’s excoriation of the UK’s political class on Newsnight in October 2013 – a clip that’s since had nearly 10 million views on YouTube. Yet Curtis is suspicious of Brand’s disdain for voting. “Who benefits from that? The unelected powerful, because you’re emotionally and psychologically disempowering politicians. The only power politicians have is the collective confidence we have in them. The most radical thing is to recapture the idea you can change the world.”

We walk downhill from the abbey, crossing into Thamesmead by one of the surviving walkways. The development is at the edge of London, where the Thames estuary widens and begins to look wild. We pass an open patch of grass, and Curtis stops to take a photo of a horse tethered to a wooden post. “I’ve got a friend who likes horses,” he says by way of explanation.

***

There’s a two-minute parody of Adam Curtis’s style that appeared on YouTube shortly after the broadcast of his last major series, All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace (2011). “This is a story,” begins the mocking voice-over, “about the rise of the collageumentary and how the medium swamped the message.” Over clips of disjointed archive footage, the parody singles out Curtis’s use of pop music (you can hear everything from Brian Eno to Nine Inch Nails in his films) and “cuts between shots so bewilderingly fast that the audience didn’t notice the chasm between argument and conclusion ... they simply went along with it.”

I find this kind of criticism somewhat odd. Since when were pop music and flashy editing unusual – or even undesirable – in mainstream television? When it comes to film-making, Curtis freely admits he’s a “populist”. The son of a cinematographer and now based in the BBC’s Current Affairs department, in the early part of his career Curtis worked for That’s Life!, the magazine show presented by Esther Rantzen. There’s more than a hint of snobbery to Curtis’s detractors – it’s always other people, the great unwashed viewing public, who are susceptible to conspiracy theories, not the clever critic who sees through them – but others have made more substantial objections.

After the broadcast of Curtis’s 2007 film The Trap, which traced the influence of game theory – the idea that humans behaved as self-interested individuals – on contemporary economic thought, Prospect magazine’s Max Steuer argued that the series “greatly exaggerates the power of ideas, and at the same time almost wilfully misrepresents them”. Others made similar criticisms of All Watched over by Machines of Loving Grace, which linked the anti-state philosophy of Ayn Rand with the “techno-utopians” who developed modern computing. At the very least, don’t his films encourage precisely that gloomy feeling – a sense that power is in the hands of an unaccountable elite – that so exercises him?

“Well, I am a creature of my time,” he concedes. We’ve found our way to a café in the shopping centre near Thamesmead, where we can chat at greater length. “What I’ve been trying to do is analyse why progressive ideas failed.

“Secondly, I’m interested in telling stories, because I like telling stories and I think ideas are important. I take particular influences of particular groups of people as a way of showing how that idea spread out. I never say this is where it all came from, this shadowy group of people. I’m telling you a story, like a novelist would, but as a factual story to try and bring it to life to you.”

What about the accusation that his style manipulates the viewer’s emotions? “I’m often accused of being a propagandist,” Curtis says. “The truth is I am a propagandist, because I am doing exactly what you see. It’s quite obvious: I’m taking a picture here, a picture there and a bit of music to create an emotional platform to get you to listen to what I’m saying. That’s what journalism should do.”

Curtis’s formula is undeniably popular. Aside from his films, he’s worked on acclaimed collaborations with the theatre company Punch Drunk and a live show at last year’s Manchester International Festival with the pop group Massive Attack. In one sense, his popularity isn’t surprising: we live in an age where emotions are foregrounded, even in factual television: as Mark Fisher writes, we are living in an age where documentary TV has increasingly taken on the form of entertainment.

Where Curtis differs is that he fervently believes in the power of stories to change the world. It’s a stance often dismissed as patrician or “elitist” in today’s media, but Curtis cites the example of the Daily Mirror in its 1950s and ’60s heyday under the editorship of Hugh Cudlipp. “The Mirror took ideas that weren’t necessarily popular and they tried to sway opinions because they thought it was morally right.” The most famous example of this was the paper’s long-running campaign against the death penalty, at a time when most of its readers – initially, at least – supported hanging. “My granddad was a working-class leftie who read the Daily Mirror. And he loved it, because it was emotional but it also was about ideas that the world could be different. And that’s where I come from.”

Our time in the café is nearly up. We chat for a few more minutes about future plans (his next project will be about “the institutions tearing themselves apart” – the fallout from the Jimmy Savile scandal and the private companies taking over services once provided by the state) before we pay up and head off in search of a bus back to central London.

***

A week or so after our interview, I get an email from Curtis. “I think I was sort of wrong about Russell Brand,” he writes. He says he still disagrees with Brand’s claim there is no point in voting. “Yet in a way,” Curtis writes, “Brand is right. And the reason is the total failure of the Left to offer an alternative idea that inspires people to have imaginative visions of alternative futures. That creates a vacuum ... [and] politics essentially becomes a process of reading the temperature of the room and adjusting the radiators to make sure everything remains stable.”

That’s as succinct a description of our current political crisis as I’ve encountered. How you react to Curtis depends on how you think his role relates to the problem. Are his films going to provide us with an “alternative vision”? No. Will they give us a comprehensive account of complex systems and how to fix them? Probably not. What they will do, however, is get people thinking and talking about the world in which they live – which to me is exactly what mass media should be doing.