In my early childhood days at a Catholic boarding school in Droitwich, there were some miraculous stories that had particular appeal. There was the wonderful one about Jesus feeding a multitude on five loaves and two fishes. And feeding them so well that, according to Mark, there was enough left over for 12 baskets.

Then there was the intriguing tale about how the Virgin Mary miraculously made her way into heaven. As the priest in charge of our daily Religious Instruction carefully explained, Mary couldn’t simply ascend to heaven in the same manner as Jesus because she was not actually divine. So instead of being forced like everyone else to go through the natural process of physical decay and death, she was bodily “assumed into heaven”. Amazing!

None of the priests who took our RI lessons seemed willing or able to elaborate on the physics of this doctrine, but I remember my 10-year-old classmate, Rollason, suggesting one night in the dormitory that Mary must have been literally sucked up to heaven through the operation of something like a celestial vacuum cleaner. Whoosh!

Yet none of these stories engaged my attention so firmly as the Catholic account of the vicissitudes of the soul, which, we were told, did not die with the flesh but was held in suspension until being reunited with the body at the final resurrection.

Souls, we learned, were rather special internal organs. They were all too readily contaminated and stained by sin, and these stains were so black and so deep that they could only be washed away by regular visits to the confessional. (This story gained some of its imaginative appeal from the manner in which it symbolically matched with the fate of a fellow pupil, Riley, who was banished from school because he had a potentially fatal spot on his lung.)

All through those early childhood days the absolute cleanliness of my soul was of more immediate daily concern than other more evident bodily manifestations, such as the appearance of pubic hair and facial spots.

But keeping a soul clean was an arduous business. For although confession promised to sweep away one’s sins, a nasty sinful stain could reappear merely by the espousal of a single dirty thought. So while one could readily remove the big black stain left by masturbation with some post-confessional penance – half-a-dozen Our Fathers and a few score Hail Marys was the usual tariff – once out of the confessional box, even a brief pleasurable thrill at the erotic noise made by Matron’s nyloned legs as she patrolled the dormitory was enough to once again mar the purity of that ever-so-sensitive internal organ.

It was Freud, or at least my teenage acquaintance with Freudian psychology, that finally freed me from the tyranny of the constantly stained soul. The news came from Vienna that the real psychic battle was not between the cleanliness of one’s soul and the ever-present allure of immoral thoughts and deeds, but between the instinctual desires of the id, a moralising agent known as the ego, and a poor psychic entity, the super-ego, which endeavoured, like the horses of Plato’s chariot (Freud’s metaphor), to mediate between the other two contenders for control.

This was welcome news. No longer was I the unhappy host of an all-too-easily stained soul, but a more complex creature. It was a model of internal psychic life that not only relegated dirty thoughts and actions to the id, but, more importantly, allocated all one’s oppressive moralising concerns about such naughty matters to the self-righteousness of the super-ego.

We do bad things. We think bad thoughts. We thoroughly despise ourselves for both our bad thoughts and our bad actions. And there really is no psychic detergent that will clear up all these contradictions. They are constantly present.

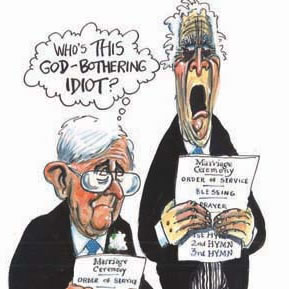

My childhood priests, immersed in their doctrinal certainties, had no time for such complexities. Their detergent model of psychic life was without ambiguity, free from all internal contradiction. How could they have been so simple-minded? Freud asked himself the exact same question. “Why is it,” he wrote, “that none of all the pious ever discovered psychoanalysis? Why did it have to wait for a completely godless Jew?”

This piece is from the New Humanist spring 2022 edition. Subscribe today.