Still Pictures: On photography and memory (Granta) by Janet Malcolm

In postwar New York, after escaping Nazi-occupied Prague in 1939, Janet Malcolm’s mother Joan was having dinner in an American household. When time for seconds came, Joan declined. In bourgeois Prague, this was a charade known as nutcení, and the host would insist until you relented. “But here ‘No, thank you’ was taken to mean just that, and the platter of delicious American food was whisked away before my mother’s sad eyes,” Malcolm writes.

The anecdote captures a key theme of Malcolm’s autobiography-of-sorts: the alienating experience of being an émigré in a strange land, your personality changed, working out where you fit. Malcolm was four when she boarded one of the last civilian boats from Europe before the war. With the aid of photographs, diaries and letters she weaves an episodic story of her family in their new country: growing up in a Czech community in Manhattan, and the years preceding her career as an acclaimed author and journalist.

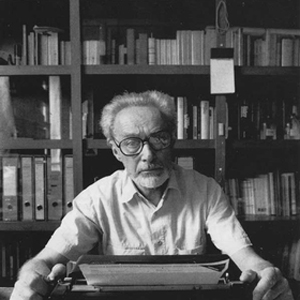

Malcolm passed away in 2021 at the age of 86. Her last work is also her first of memoir, after a long career stretching the boundaries of nonfiction. Her book The Silent Woman, a biography of Sylvia Plath, called into question the entire voyeuristic project of biographies. In Forty-One False Starts, about the artist David Salle, she wrote in a disjointed form that merged with Salle’s collage-like paintings. The Journalist and the Murderer has become a staple in journalism courses for its biting insights into fraught reporter-subject relationships. Whatever Malcolm wrote about, one obituary said, “Her real subject was often the writing process itself.”

This book sees Malcolm’s probing gaze pointed at her own life. She describes a classroom crush, who did not return her affections. “I was part of the background of ordinary girls, who secretly loved and, unbeknownst to ourselves, were grateful for the safety of not being loved in return,” she writes. She analyses what it means to appear a “charming” person, to flatter and show attention. “When I ask someone a question – either in life or in work – I often don’t listen to the answer. I am not really interested. (The use of a tape recorder during interviews permits me to counteract this obvious disqualification for my job.)”

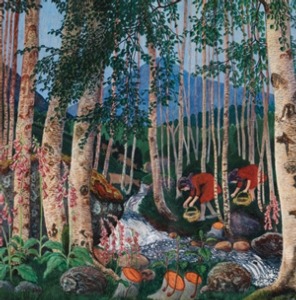

The strongest sections question memoir itself. Our lives are “like photographic negatives”, she writes, but only a few are developed into photographs and become our memories. She resists this urge to narrativise life from what sticks out of the fog of time. Her father Joseph “loved opera, birds, mushrooms, wildflowers, poetry, baseball... My mind is filled with lovely plotless memories of him.” She warns autobiographers against using memories that seem to have a plot – “conflict, resentment, blame, self-justification”. These little flashes make us rethink the reading of all memoir.

Malcolm’s relationship to her mother forms the book’s emotional core. She looks back “ashamed and mortified” at her distant young self, unable to give Joan the love she craved. Her mother would spiral into depression when Malcolm left letters unanswered or replied in glib jokes. “How could I have been so cruel and callow?” she reflects.

Reading Still Pictures, I searched to pinpoint why the book feels so surprising. Some part is no doubt that, in 2010, Malcolm wrote of abandoning autobiography, arguing against its reliance on spotty memory. “If an autobiography is to be even minimally readable,” she wrote, the autobiographer “must not be afraid to invent. Above all he must invent himself.” As a journalist she found this repellent. Yet 13 years later, here the book is.

Perhaps hardest to pin down is the question of motive. Malcolm flies past a variety of topics without landing on any definitely. It’s hard to know who exactly the book is for. Those interested in memory’s slipperiness? At times. Those who escaped persecution to begin life anew? For sections, yes. Fans seeking the person behind her journalism? If so, they’re bound to be disappointed (she remains private, leaves too many mysteries unsolved; an affair is mentioned, unexplained, then quickly shuffled offstage). The collection seems to lack a coherence that, if Malcolm herself were reviewing it, she’d no doubt spot.

But this may have been her intention all along. Rather than circling around a central theme, like planets orbiting the sun, this engaging little book is more a series of flashing asteroids. And this is a more accurate description of how memory operates than the polished autobiographies in many bookstores. Yet again, Malcolm matches form to function. She gives us shooting stars – burning brightly in all directions before fizzing out before our eyes.

This piece is from the New Humanist spring 2023 edition. Subscribe here.