The novel opens at midnight, July 1841 in New Jersey where an unknown killer deposits the lifeless body of Mary Rogers, the famous “beautiful Seegar girl” from Anderson’s Liberty Street coffee shop, in the Hudson River. This was the murder that inspired Edgar Allen Poe to write The Mystery of Marie Roget, the sequel to his prototypical detective story The Murders in the Rue Morgue. The Blackest Bird is also a detective novel which uses history and fiction in equally generous amounts to serve up a thrilling and substantial book.

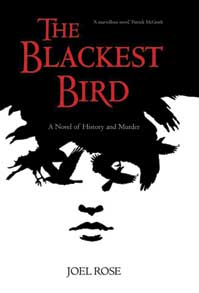

Despite huge media interest in the crime and Poe’s immortalisation of Mary Rogers, the case was never solved. This is what Joel Rose sets out to do in The Blackest Bird, skilfully weaving fact and fiction in a satisfying meditation on a fascinating writer at a fascinating moment in American history.

Despite huge media interest in the crime and Poe’s immortalisation of Mary Rogers, the case was never solved. This is what Joel Rose sets out to do in The Blackest Bird, skilfully weaving fact and fiction in a satisfying meditation on a fascinating writer at a fascinating moment in American history.

In Rose’s telling, Poe’s involvement and obsession with Mary’s murder – Poe had been a regular at Anderson’s and knew the real Mary – leads to Poe himself being considered a suspect. Poe’s outspoken reviews and constant opposition to unfair publishing laws made him a lot of enemies, particularly the publisher, Harper, whose dishonesty included making pirate copies of English novels and who opposed copyright for American writers. So Harper implicates Poe. And although we are aware that he is full of spite, we can’t be quite sure of Poe’s innocence. His mournful figure haunts these pages as he makes his way through a world of dishonesty and skulduggery, constantly changing address and doggedly pursued by the lonely High Constable, Old Hays.

Reportedly Joel Rose – novelist, journalist and a story writer at DC Comics where he wrote scripts for Superman and Batman – spent 17 years researching The Blackest Bird and his dedication pays off in the gripping depiction of the dangerous, fledgling city of New York.

The flawed city comes alive with its crooked politicians, pretentious literary ladies and gentlemen and especially those gloriously named local gangs; the Plug Uglies, the Dead Rabbits, the Shirt-tails, the Forty Little Thieves. There are stirring descriptions of actual events: the fire at the Tombs which followed the wedding held for murderer John Colt (brother of Samuel, inventor of the revolver) the day before his execution; the wake of Irish gang leader Tommie Coleman. Most wonderful of all is the account of a midnight body-snatching where the robbers flee from the graveyard at the sight of the black-clad figure of Edgar Allen Poe wandering among the graves. In the distance, Old Hays watches Poe watching the grave robbers. Can Edgar Allen lead Old Hays to the killer or is the real culprit Poe himself?

Unlike Poe’s Chevalier Dupin, Old Hays is not sure that ratiocination alone will yield the criminal; he favours instinct too. He also “believes that he can distinguish the criminal physiognomy from the physiognomy of the honest man. He has made a lifetime study of the science, exploring fully the face … as index to character.”

Throughout the novel, Rose plays with the form and idea of the detective story and we are made conscious of Poe’s importance as the author of the first detective story, The Murders in the Rue Morgue, while Old Hays and his daughter Olga pore over Poe’s original and edited versions of The Mystery of Marie Roget, searching for vital clues to the identity of Mary Rogers’ killer.

As often with novels which braid fact and fiction, there are points at which you feel you have to check the history, to disentangle documented fact from the author’s embellishment. Indeed, turning to the sources revealed a fascinating and mysterious tale – and an incredible number of books on the subject – but it broke the spell of the novel. In the end I abandoned the fact-checking and gave myself wholly to Rose’s satisfying version of history. I would advise other readers to do the same.

There are other treats in this book, not least the opportunity to read Poe’s poem “The Raven” again. Fittingly, “The Raven” comes at a turning point in the story as the narrative moves towards its climax and Poe moves towards his death.

This is a novel preoccupied with the pursuit of justice: Poe’s search for better rights for American writers, his obsessive tracking of Mary’s killer, Hays’ battle to bring criminals to justice. Can this be why the detective genre is so fascinating? In real life, justice is not always seen to be done. As Hays remarks to Poe, “Sometimes in a court of law, a man does not always get justice. Sometimes a man is sorry for what he has done, contrite, but the court is unable to see his remorse.” Detective novels offer the opportunity to correct the grubby compromises and frustrating irresolutions of the real world. Rose does this brilliantly.

Rose also sees to it that justice is done to the memory of Mary Rogers and to the flawed personality and tragic genius of Edgar Allen Poe. His wraith-like character stalks these pages, often drunk, always struggling. I found myself riveted like that first audience listening to Poe’s reading of “The Raven”, described through the eyes of the dogged constable, where “the expressions on the faces in this room qualified to Hays as nothing more than ‘mesmerised’”. ■

The Blackest Bird is published by Canongate