Dorothea Lange was one of the great documentary photographers. Her work is known world-wide and helped shape our very conception of what documentary photography is. Her best-known work, photographs of migrant farmworkers and sharecroppers of the Depression of the 1930s, is so widely published that those who do not know her name almost always recognise some of her pictures.

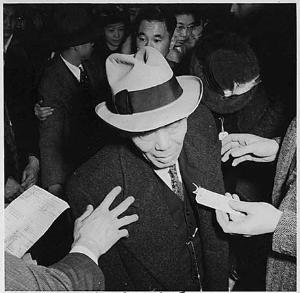

But few know that she was hired by the War Relocation Authority of the US Army to photograph the internment of 116,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. Most of these photographs have never been published. They were suppressed for the duration of the war, and quietly placed in the National Archives afterwards. These photographs exemplify Lange’s mastery of composition and of visual condensation of human feelings and relationships. They also stand as a condemnation of internment without trial which has an obvious relevance today.

Born in 1895, Dorothea Lange grew up in Hoboken, New Jersey, and weathered difficulties that might have flattened someone with less energy and drive: polio at age seven, which left her slightly but permanently disabled, and her parents’ separation, which sent her mother out to work and left the adolescent Dorothea much on her own. Her most important teacher became the city of New York. She spent much of her time walking the streets – from the immigrant Lower East Side, where her mother worked at a library, uptown past the millionaires’ row on 5th Avenue. She discovered modern art, became electrified by Isadora Duncan and found her way into photography – working in several portrait studios, first answering telephones, then as a darkroom apprentice and finally as a wedding photographer. Eager for adventure, she travelled with a friend to San Francisco in 1919 and lived in California for the rest of her life.

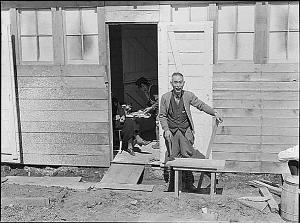

There she built an extremely successful portrait studio. She married a well-known painter of western Americana, Maynard Dixon, and socialised in bohemian art circles. She developed a photographic style – flattering, a touch unconventional, even arty – that attracted the most cultured of San Francisco’s elite. But the depression of the 1930s hit her hard. Her business suffered and she began to feel trapped in her marriage and her studio. Like thousands of artists, she grew concerned with the widespread economic distress and sympathetic with the growing labour movement. She began photographing in the streets for the first time. She made pictures of the breadlines, the unemployed sleeping on park benches and the great longshoremen’s strike of 1934. Progressive agricultural economist Paul Taylor saw her work and brought it to the attention of the Farm Security Administration, for which she worked from 1935 to 1939. She and Taylor divorced their respective spouses and married, working together on behalf of sharecroppers and migrant farmworkers. They travelled repeatedly through the Imperial and San Joaquin valleys, land that had become extraordinarily fertile after massive irrigation projects, photographing and interviewing migrant farmworkers and dust-bowl refugees, in the scorching heat of summers before air conditioning. They moved throughout the deep South, studying and photographing white and black sharecroppers and wage-labourers growing cotton and tobacco and distilling turpentine. In the summer of 1936 Lange logged 17,000 miles.

Defying stereotypes about the disabled, Lange was a strong woman. She often climbed on top of her old Ford station wagon to photograph. She slept little, developed film in motel bathrooms with no ventilation, and worried that the heat and humidity would damage her film.

Lange was not unique in her newfound concern for poor and working-class people – a very large proportion of photographers and artists moved to the left at this time, including several from Dixon’s and Lange’s crowd in San Francisco. But very few of them foregrounded racism in their work. Lange’s consciousness was raised by Taylor, who was at the time virtually the only white scholar to study Mexican Americans, and by California itself. By the 1920s Mexicans became the overwhelming majority of California farmworkers, as their poverty and lack of citizenship made then so exploitable.

Still, in their opposition to the internment of the Japanese Americans, Lange and Taylor were almost alone. Only a tiny minority of white Americans openly opposed the imprisonment of these innocent people. Liberals and leftists, even those who explicitly opposed racism, remained silent because they wanted to support all necessary measures to defeat the Axis powers – and their beloved President Roosevelt told him that the internment was necessary.

Two questions immediately arise: why did the WRA want photographic documentation and why ask Lange, already known as a progressive, to do it? Taylor told an interviewer that making a photographic record was by then “the thing to do” in government. Moreover, “government” was by no means of one mind – if the Army’s Western Command, who ran the evacuation and the camps, had been consulted, there might not have been any photographs. A photographic record could protect against false allegations of mistreatment and violations of international law, but it carried the risk, of course, of documenting actual mistreatment. (A measure of how important it seemed to prevent such a calamity was that the internees were forbidden to have cameras.) The WRA employed Lange for the job because she had proven a reliable government photographer in the 1930s, documenting the depression for the Farm Security Administration, and because she lived in San Francisco, central to most of the Japanese American population.

The internees were never even charged with a crime, let alone convicted. Two thirds of them were US citizens, born in the US the remainder could not have become citizens because at that time people of Asian origin were prohibited from naturalisation. But after the bombing of the US naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in December 1941, and its destruction of a substantial portion of the American fleet, the understandable American anger focused not on the Japanese Imperial government and its expansionist goals but on the Japanese as a race.

Anti-Japanese racism was already well developed on the west coast, but after the attack it was ratcheted up by politicians and the press; when rumours that Japanese Americans were to be interned began to circulate, big agribusiness interests joined in the barrage of defamation, probably because they thought (correctly) that they would be able to buy Japanese farms at discounted prices. Now the pejorative verbal and visual rhetoric about Japanese Americans was intensified and expanded to include completely uncorroborated allegations of disloyalty and treason. As the Los Angeles Times justified the policy, “A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched.”

Rumours of spies, sabotage and attacks circulated widely. A few authenticated attacks – for example, in February 1942 submarines shelled a Santa Barbara oil refinery; in June a submarine shelled the Oregon coast; in September a submarine launched incendiary bombs near Brookings, Oregon – escalated the fear-driven hysteria, although no one was hurt and damage was minimal. But significantly, the order calling for the internment preceded these attacks. Military leaders fomented the anti-Japanese fever. General DeWitt, head of the US Army’s Western Defense Command, opined that “The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on American soil, possessed of American citizenship, have become ‘Americanised,’ the racial strains are undiluted. The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken.” That kind of hysterical illogic went largely unchallenged.

In February 1942 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued executive order 9066, requiring the relocation of all Japanese Americans, regardless of their citizenship. The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was established to organise their removal, and hired Lange to document the program photographically. Despite her political consciousness Lange was not prepared for what she saw.

Her photographs show people ripped from their lives at short notice, forced to sell property at great losses, to give up homes and furnishings, leave jobs and schools; lined up, registered, tagged like packages, allowed to bring only what they could carry; then housed in crude barracks (and in one location in horse stables at a race track); surrounded by prison regulations: no cameras, no books or magazines in Japanese, meals in large mess halls with food often ladled out from garbage cans, collective toilets, whole families sleeping in one “room” barely partitioned off from adjoining families; singles sleeping in huge wards with long rows of cots.

Lange’s photographs make her condemnation of the policy quite clear, clear enough that the army unit that hired her did not want the pictures publicly released. After the war, they were deposited in the National Archives. A few have been used by scholars but Lange’s images have never been published or exhibited on their own.

I came across these photographs in the process of writing a biography of Dorothea Lange, in which I examine the visual culture of the Depression and the New Deal. These photographs, however, could not await the completion of the biography. One hundred and nineteen of the approximately 800 photographs she made appear in a new book along with an essay by me on Lange and an essay by Gary Okihiro about the internment. Their relevance to internment without charges today seems to me to require bringing them to public attention.

Linda Gordon is Professor of History at New York University. Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment is published by Norton.