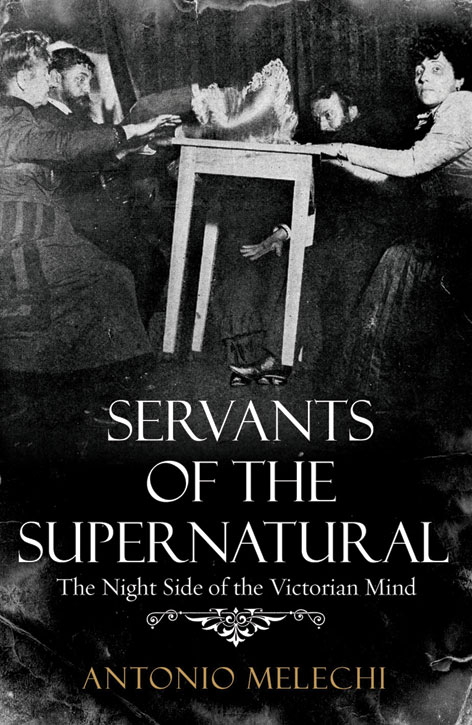

This is one of the most balanced and thoroughly engaging accounts I have ever come across of the Victorian spiritualist demimonde. Melechi traces the European origins of the séance to the “animal magnetism” of Anton Mesmer (1734-1815), an opportunistic, quasi-scientific magpie who “pilfered the language and symbolism of Newton” to postulate and promote across fashionable pre-revolutionary Paris the existence of an hitherto unknown occult force. It was, though, Melechi claims, Mesmer’s timely marriage to a wealthy widow that was the real secret of his unqualified international success.

This is one of the most balanced and thoroughly engaging accounts I have ever come across of the Victorian spiritualist demimonde. Melechi traces the European origins of the séance to the “animal magnetism” of Anton Mesmer (1734-1815), an opportunistic, quasi-scientific magpie who “pilfered the language and symbolism of Newton” to postulate and promote across fashionable pre-revolutionary Paris the existence of an hitherto unknown occult force. It was, though, Melechi claims, Mesmer’s timely marriage to a wealthy widow that was the real secret of his unqualified international success.

The book opens, aptly enough, not a stone’s throw away from today’s New Humanist offices, in Gower Street. Here, in the wards of University College Hospital, the reader is introduced to John Elliotson, Professor of the Principles and Practices of Medicine, for a startling demonstration of what he describes as “this new and mysterious science”.

Back in the mid-19th century, whether you believed the onset of Mesmerism was “a demoniacal mummery” or “the most extraordinary event in the history of human science”, there was certainly no ignoring its impact. The idea that living matter was somehow charged with an invisible substance analogous to electricity polarised opinion across the board. The Times might well have described the phenomenon (rather snootily) as “a mere exhibition of revolting imposture”. It nevertheless attracted the curiosity of literary cynosures like Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope, Thomas Carlyle, the Robert Brownings and George Eliot, all of whom Dr Elliotson welcomed to his wards to see “the force” at work.

At this point enter, from across the Atlantic, an illegitimate wunderkind, one Daniel Dunglass Home. In no time at all, the man witnesses handkerchiefs snatched from hands, apron strings invisibly untied, an accordion that begins to play itself, the mahogany table he’s sitting at rising “unaided” three feet into the air. I’d challenge any reader not to react to such revelations as these (as I did) with a certain scepticism – until they discover the eyewitness in question was none other than Sir David Brewster, Fellow of the Royal Society, a scientist of the greatest renown, inventor, inter alia, of the ingenious lighthouse illuminator.

At another séance Alfred Russel Wallace – explorer, naturalist, co-architect of natural selection – recorded how he watched “Fifteen chrysanthemums, six variegated anemones, four tulips, five orange-berried solanums, six ferns, and two different sorts of Auricola simensis” as they came raining down upon the table “all fresh and cold and damp with dew”.

Inevitably, there were arch-dissenters not for a moment “duped” by such evergreen pyrotechnics. Michael Faraday stands out as a beacon of common sense and level-headedness, as do Thomas Huxley, Thomas Wakley (editor of The Lancet), Charles Darwin and his amanuensis, Professor of Zoology at UCL, Edwin Ray Lankester.

Melechi loves a foreign turn of phrase, be it a vera causa, a vita scholastica, or a veritable célébrité. Sometimes, though, his linguistic legerdemain veers perilously close to the indigestible.

He tells a convoluted and difficult tale with passion and insight.

Servants of the Supernatural is published by William Heinemann