Just before Christmas last year, Republican presidential candidate Mike Huckabee, an ordained Southern Baptist Minister, launched a festive campaign advertisement. Sitting before a roaring fire, and dressed in a homely red sweater, the insurgent candidate wished the voters of Iowa a happy holiday, and a break from the travails of the campaign. But, asked the press the next day, why did there appear to be a glowing crucifix over Mr Huckabee’s right shoulder?

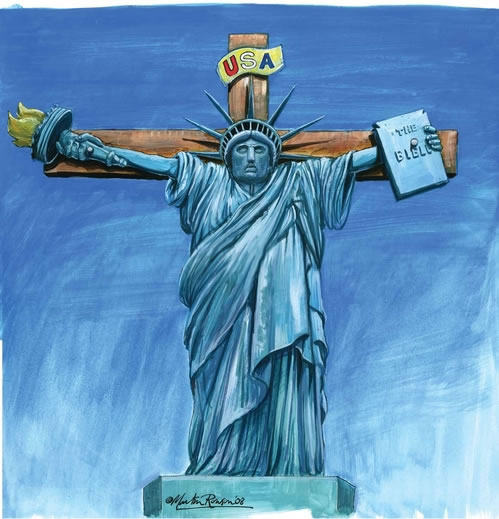

A minor scandal erupted. Commentators and opponents debated: was this a not-so subtle attempt to subconsciously reach out to hundreds of thousands of devout voters? Or was it, as the campaign suggested, merely a bookshelf, caught in the wrong light? Despite the candidate’s strenuous denials, this silliest of scandals rumbled for days. It confirmed, as if confirmation were needed, that religion in America remains a deeply political subject.

A minor scandal erupted. Commentators and opponents debated: was this a not-so subtle attempt to subconsciously reach out to hundreds of thousands of devout voters? Or was it, as the campaign suggested, merely a bookshelf, caught in the wrong light? Despite the candidate’s strenuous denials, this silliest of scandals rumbled for days. It confirmed, as if confirmation were needed, that religion in America remains a deeply political subject.

From Barack Obama’s scrabble to explain off-colour remarks made by his pastor to Mitt Romney’s battle to explain his Mormon faith, religiously themed controversies have rarely been far from the headlines during the 2008 election. Most recently, the furore over Obama’s statement that “bitter” economically disadvantaged voters tended to “cling to guns or religion” came closer than any other to upsetting his slow-march to the Democratic nomination.

After the era of George W Bush you might have thought religion couldn’t play a bigger and more important role in American politics. But the current campaign, with candidates on both sides courting the religious vote more professionally than ever before, shows you would be wrong. Religion in general and evangelical voters in particular are playing a role in this contest at least as significant as in previous polls.

Only, this time, the way in which their influence is being felt is different. Rather than lining up monolithically behind George Bush, intriguing fractures are appearing in the normally reliably Republican evangelical vote. And, with Democrats making more efforts than ever before to speak the language of faith, some experts believe that the “values vote” is up for grabs for the first time in a generation.

Readers of this magazine may find it difficult to imagine any way in which religion could play a more prominent role in American politics. And, indeed, there are a number of sociological trends that could be taken to imply the possibility of a retreat, albeit a small one, in the importance of religion in public life.

On the one hand many of the most famous organisations of the Christian Right, along with their most famous leaders, seem to be in decline. Many of the iconic groups from the rise of the religious Right, including the likes of the Family Research Council and Christian Coalition, have either disappeared or lost influence.

Harvard Academic Richard Parker claims this decline is largely because these organisations have completed the ultimately political job they set out to do: “The cycle of politics associated with the movement of white Democrats, from the South and Texas, into the Republican party is largely complete.” As a consequence, he argues, “the functional power of the para-religious organisations such as Focus on the Family, Christian Coalition or the Moral Majority is spent.”

This change has been felt at the top of the evangelical Right, where a combination of death, scandal and organisational decline has combined to bring down many prominent Christian leaders. The influence of both Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell declined in step with the organisations they once led. Other evangelical leaders found themselves tainted by proximity to power, with former Christian Coalition Director Ralph Reed, in particular, finding his political aspirations wrecked by links to disgraced Republican lobbyist Jack Abramov. Sexual misadventures also played a part, most recently when prominent evangelical Ted Haggard was caught up in a juicy scandal involving gay prostitution and crystal meth. Only James Dobson, the leader of Focus on the Family, has managed to retain the type of prominence and influence that Falwell or Robertson enjoyed at their peak.

At the same time as these various falls from grace it is also worth noting that, against the backdrop of assumptions of the steady rise of American religion, secularism in the United States is on the increase. The American Religious Identification Survey suggests that the proportion of “non-religious” Americans more than doubled over the course of the 1990s to around 15 per cent of the population. The number of self-identified Christians is in decline, as is the proportion of the country regularly attending church.

Could the recent anti-theological efforts of Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins be bearing early fruit? Unlikely, thinks Amy Sullivan, author of a recent book on the changing nature of the evangelical movement. Instead, she suggests two long-term underlying trends changing American religious identification.

First, the US has recently seen the emergence of a cohort of “second generation” secular youth, raised by secular parents. Those brought up without religion are more likely to be non-believers themselves. Second, given that unmarried individuals without children are less likely to go to church, delays in the average age of American marriages are creating a “life-cycle effect”. Although most return to the fold when they have children, the increasing number of single people means the overall cohort of non-church goers has grown.

Yet despite the decline of the great institutions of the religious Right, and with secularism the fastest growing faith in America, religion’s political significance continues to increase. Why so? At least in part, credit must go to efforts by the Republican Party over the past decade to mobilise religious voters, and in particular to George Bush’s svengali Karl Rove.

Speaking in 2001, Rove argued that George W Bush’s first election victory had been narrower than it needed to have been, in large because the party had failed effectively to reach out to evangelical voters. “If you look at the model of the electorate,” he argued, “the big discrepancy is among self-identified, white, evangelical Protestants, Pentecostals, and fundamentalists. There should have been 19 million of them, and instead there were 15 million of them.”

At the next election Rove made unprecedented efforts to convert those “missing” four million Christian voters. His party developed a new line in “religious outreach”, spending more time and money appealing to faith organisations than any other campaign in history. Campaigns reached out at the level of local church parishes and individual congregations, employing special staff to organise faith communities, and to recruit and organise in religious communities. Evangelical voters began to act as foot soldiers, organisers and drill sergeants for the Republican Party.

The result? Bush’s second victory crystallised the importance of America’s 55 million evangelical voters. Political scientist John Green, a fellow at the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, argues that American voters have long been divided by religious affiliation. However, only in 2004 was the divide between different faiths complemented by a second “God gap” explained by religious attendance. Put simply: if you went to church, chances were you voted Republican. Not only that, but attendance at church was now just about the most reliable predictor of voting intention – a factor more likely to explain how someone would vote than class, gender, region or age.

Fast-forward to 2008, and three factors go some way to explain the continued importance of this gap, and attempts to close it. First, the Democrats woke up to religion. In the aftermath of defeat leaders on the left committed to finding new ways to communicate with so-called “values voters”. Hillary Clinton was among the first to try a new tack. Three years before announcing her candidacy she gave a God-laden speech on abortion, describing herself as a “praying person” who was “lucky enough to be born into a praying family”, and mentioning religion on more than a dozen occasions in an attempt to cast off her image as a godless liberal. Others followed suit, with even the previously secular-friendly figures like Howard Dean getting in on the act.

The results of this awakening were clear from the early days of the 2008 campaign. Obama’s easy facility with religious language and preacher speaking style caught most attention. But all the candidates took religion seriously in their campaign organisations. Religious outreach coordinators were hired. Faith advisory boards were convened. Regular emails and conference calls were churned out to touch base with religious leaders. Prayer breakfasts became common, speeches were peppered with scripture, and religiously themed meetings – for instance the “faith forums” run by Barack Obama during the New Hampshire primary – became a regular part of the campaign. And, while not changing many of their policies, candidates began to experiment with new ways to communicate unpopular messages – for instance on abortion and homosexuality – to make them easier on religious ears.

The decision of Democrats to take religion more seriously combined with a second important change: a growing split between the old leadership of the evangelical movement and its grass roots. In 2004 the leadership of the evangelical movement rallied to George Bush’s flag. Yet in 2008 the movement seemed more confused. None of the candidates ticked the right boxes. Lacking one clear candidate, its leadership split. Reverend Pat Robertson, for instance, surprised most observers by plumping for Rudolf Giuliani. Many others threw their lot in unenthusiastically for either Romney or Fred Thompson.

Pastor Randy Brinson, head of Redeem the Vote, an organisation modelled on MTV’s Rock the Vote working to register Christian voters in the election, claims this was the critical step in exposing a growing split between the bosses and the pews. “Ordinary Christian voters saw their leadership working for Romney and Thompson, and they didn’t like what they saw,” Brinson says. “Mitt Romney represented everything about rich, out of touch, country club Republicans but the elites lined up with them anyways.”

Many evangelical voters, he argues, have been unfairly characterised as only caring about abortion and limited government. In fact many increasingly wanted to hear their leaders talk about issues like poverty reduction, education reform or the environment. So when Mike Huckabee emerged as a candidate who talked about these issues – who could, as Brinson puts it, talk the language of “Wal Mart, not Wall Street” – Evangelical voters were ready to listen.

This growing rift between old leadership and the grass roots combined with a third factor. In this election previously marginalised groups within the evangelical movement were able to act. And it was Huckabee’s insurgent candidacy that brought this to the fore.

The 2008 election campaign has seen the rise of a new type of campaign. New forms of organisation, largely made possible by the internet, have allowed traditional campaigns to organise supporters and raise staggering amounts of money in “small dollar” donations. The same trends are visible on the Christian Right. Smaller Christian groups decided to take matters into their own hands.

Brinson’s Redeem the Vote was one such organisation, and one lucky enough to own a massive email list of tens of millions of evangelical voters, developed during a marketing campaign for the film The Passion of the Christ. (His group claims some credit for helping to register large numbers of previously unregistered evangelical voters in 2004, contributing to George Bush’s victory.) He offered to use this list to help promote Huckabee’s candidacy. He makes bold claims for the results. “When we started out working for him, he was polling less than one per cent in Iowa. Between the summer of 2007 and the time of the Iowa caucuses we were able to chart a direct correlation between the number of emails we sent out and his poll numbers.”

Brinson makes impressive claims for the result. Powered by support from a previously unheard-of organisation, and raising money largely from thousands of small dollar donations, Huckabee went from nowhere in the polls to winning the Iowa caucuses in a couple of months. His candidacy didn’t have enough juice to win the race overall, proving perhaps that evangelical support alone is not enough to win. But the fact that he had a shot – despite being ostracised by mainstream Republicans and much of the evangelical leadership – goes some way to proving the dynamism of these changes in the evangelical movement.

These three factors, when combined, go some way to explaining religion’s changing electoral role. Democrats are treating religious voters as potential converts. A split has emerged between the evangelical movement and the changing priorities of its grassroots. And the grassroots, tired of being taken for granted by the Republican Party, are changing the way they think and organise. But what is the ultimate result? Is a more liberal species of evangelical emerging? And, if so, might they vote for a Democrat?

One currently fashionable notion states that the sum total of these changes will be a new, more progressive strain of religious sentiment. Recent books by Amy Sullivan, EJ Dionne of the Washington Post and others have argued that the God gap is closing in part because of the rise of a kinder and gentler evangelical movement. These authors identify a new breed of church leaders, ranging from megachurch pastors like Rick Warren and Joel Ostein to progressive evangelicals like Jim Wallis. These leaders balance their interest in issues like abortion with concerns for a range of “progressive” issues like global warming and poverty reduction. These issues, in turn, allow them to reach out to a new generation of younger evangelicals, and also to Democratic politicians.

An example of this new engagement in practice came in the immediate aftermath of the flap about Senator Obama’s “religion and guns” comments. In the days following the story, both Obama and Clinton attended an event known as the “Compassion Forum”. The Forum, hosted appropriately at Pennsylvania’s Messiah College, was organised by a range of religious groups, from traditional to the more liberal. Its blurb suggested that “Now more than ever, Americans motivated by faith are bridging ideological divides to address domestic and international poverty, global AIDS, climate change, abortion, genocide in Darfur, and human rights and torture.” During the evening’s debate the two Democratic candidates traded political blows about Obama’s comments, while also dropping references to scripture and answering probing questions about their favourite Bible stories. John McCain did not even attend.

High-profile events in which leading Democrats hobnob with top evangelicals prove that a shift has occurred over the last four years. But can we really expect large numbers of previously Republican evangelical voters to switch? It seems unlikely. Polls suggest that core evangelical Protestants remain unlikely to vote for a Democrat. A range of “firewall” issues – from abortion to gay rights and gun control – still stand in the way. And while younger evangelical voters do seem less enamoured with Republicans, they are now more likely to identify as independents rather than Democrats. Despite their efforts to speak the language of faith, neither Clinton nor Obama can reasonably expect to break the Republican monopoly this time round.

Nonetheless, whoever wins the Democratic nomination will face in John McCain a candidate who talks rarely about faith, and isn’t especially attractive to religious voters – leading to suggestions that evangelicals may choose to abstain. And Pew Forum’s analyst John Green has speculated that a couple of groups previously won over narrowly by George Bush – for instance less observant Catholics and less observant mainline Protestants – could switch allegiances. In a close race, even small shifts could have an impact. Perhaps more important is that religious voters are being contested at all. Faith issues, and faith voters, are no longer off limits to Democrats. The end of the old religious Right may have begun. But the importance of religion to American politics isn’t going to decline any time soon.