Our culture - probably all cultures where they do storytelling, which is all of them - has been more shaped by comedy than by tragedy. We potter about the planet creating internal models of what we see and what happens to us, and I'm pretty sure that for every Euripidean tragic reversal in our inner landscape, there are thirty knob gags, forty pratfalls, fifty bells set a-ringing by those endless and numberless gaps between aspiration and reality that carve up our world that it's the comedian's role to map.

Poets aren't the unacknowledged legislators of the world. It's comedians who do that. Test it on yourself. Visualise a crumbling, powerless, shifty old geezer propped up by his son, whose own miserable life is seemingly going nowhere. Do you see Oedipus at Colonus? No. You see Albert Steptoe at Shepherd's Bush. Admit it.

Poets aren't the unacknowledged legislators of the world. It's comedians who do that. Test it on yourself. Visualise a crumbling, powerless, shifty old geezer propped up by his son, whose own miserable life is seemingly going nowhere. Do you see Oedipus at Colonus? No. You see Albert Steptoe at Shepherd's Bush. Admit it.

Or how about a loser who can't get the girl or anything else, transformed by the ghost of a dead film star into the man he always hoped to be? How about a musician - the second-best jazz guitarist in the world - haunted by Django Reinhardt, the only man better than him, so that when they finally meet, he faints? How about a man who is going fuzzy round the edges, literally blurred, who can only be brought back into focus by others wearing glasses to see him clearly? How about a bank robber who fails because he argues with the teller about his handwriting? How about Manhattan?

The list could go on and on, but you'll have got the point: these are all the creations of Woody Allen, and if you disagree that Manhattan falls into that category, pull up some Gershwin - the Rhapsody in Blue, or the slow movement of the Piano Concerto - and see what flickers into Panavision in your mind's eye. Manhattan imposed itself on Gershwin's imagination and came out in music; Allen took the music and reverse-engineered a monochrome Manhattan from it, and that's how the city has stuck. He fixed it, like a Victorian entomologist. Anyone who saw Manhattan only after seeing Manhattan will have been faintly surprised that it was coloured, and there was no soundtrack.

Yet there's an odd, uneasy disjunction at the core of Allen's work (which has been going on for over half a century now, since 1954, when he started work on The Ed Sullivan Show). Try to extrapolate Woody Allen's movies from his writing - or vice versa - and it just can't be done. His latest book, Mere Anarchy - a collection of what Allen's great hero, the satirist SJ Perelman, called his "feuilletons" - epitomises the difficulty.

Mere Anarchy is, almost without exception, pure Perelman. The helter-skelter flight into bathos, the wild gourmet extravagance of the vocabulary (never use a word when you can deploy a refulgent feu d'artifice of rodomontade), the bringing to bear of heavy-calibre linguistic invention on the tiniest and most claustrophobic of diegeses (a man called in to "novelise" the Three Stooges; an exchange of angry letters about a kid's summer movie project; a man getting a suit made from high-tech fabric); and, above all, an almost total divorce from reality.

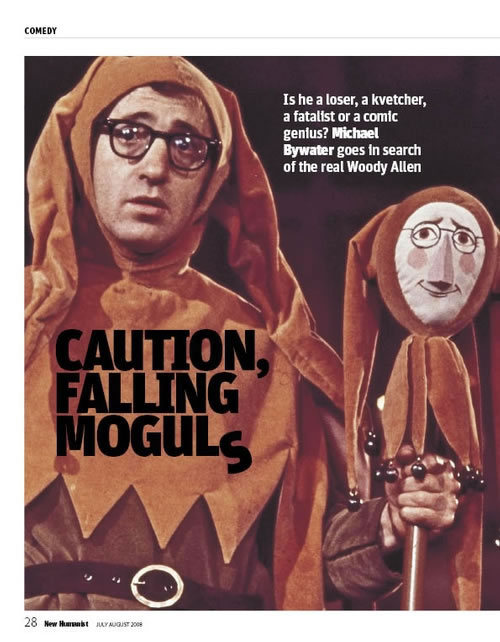

The names, as names do, signal the genealogy: Hal Roachpaste, Miss Velveeta Belknapp, Mike Umlaut and his boss Mr Ectopic, Flanders Mealworm, E. Coli Biggs. The tone is Marx Brothers, with whom Perelman briefly worked, but the invention glitters like Perelman, whether in the exaggerated orotundity ("Harvey Bidnick is a witless boor, a motormouthed little proton who fancies himself amusing but numbs his guests with relentless one-liners unfunny even on the borscht circuit fifty years ago") or the tumbling Yidlish syntax of insults ("The man stood - and if I'm lying my wife should perish in an acid bath - stood over and badgered your schlimazel Algae, who if you'd take my advice you'd toss the kid a little Ritalin once in a while maybe he would now and then stop with the fidgeting"). Even the titles of the pieces are pristine Perelman - "Caution, Falling Moguls", "Sing, You Sacher Tortes", "Glory Hallelujah, Sold!", "Above the Law, Below the Box Springs" - and pure New Yorker at that; no surprise, since many of the pieces in Mere Anarchy first appeared in the magazine which was for so long Perelman's spiritual home and fiscal cornucopia.

But Perelman touched, at least tangentially, on events in his own life: his travels, his marriage, his Anglophilia, his susceptibility to pretty young women, his farmhouse, himself. Allen, in this lambent salmagundi (see; it's catching), is nowhere to be seen.

And that's the greatest weakness in the book and in his written and stand-up work in general. The "I" is never him, not even slightly. Sometimes that imaginary narrator is pure genius, like the man facing hanging by Klansmen whom Julian Baggini quotes in his recent book Complaint (and how appropriate that he should quote the Great Kvetcher in that context): "And suddenly my whole life passed before my eyes. I saw myself as a kid again, in Kansas, going to school, swimming at the swimming hole, and fishing, frying up a mess o' catfish, going down to the general stores, getting a piece of gingham for Emmy-Lou. And I realise it's not my life. They're gonna hang me in two minutes, the wrong life is passing before my eyes.'"

How weird is that? Not very, for Allen; the wrong life is constantly passing through his typewriter keys. The characters he adopts are purely fictive, but the technique he uses was derived by Perelman to create a comic distance between the small realities and the vast pomp and ceremony of the language in which he described them.

Remove the link to reality (and the world of Allen's feuilletons is a reworking of a fictional America sometime around the 1930s, populated by shysters, grifters, Jewish sneaks and moguls and all the paraphernalia of the '30s romantic comedy, distorted beyond reason) and the language becomes an oddity, cut off from its function. It's a little like those stunningly virtuoso encores that the great pianists had up their sleeves; until you have heard the great Michelangeli (I think it was) end a perfect recital with a hideously complex Blue Danube, you've lived.

In the end, it doesn't reveal but parades, demonstrates, twirls and flounces. It does it splendidly, but it's like the women in Stringfellows, dancing on poles: once the music stops, the show's over. You can even see the technique at work (occasionally you can only see the technique at work): write it in plain, then go over it with a thesaurus. The result is a kind of logorrheic bathos: brilliance in the service of triviality.

Arguably, in one sense, he's spot-on, as was Perelman: brilliance in the service of triviality is a good representation of his beloved Manhattan and, perhaps, of the idea - or at least the reality - of the city in general.

But there is one other point at which it collides not only with reality but with the films, too. Allen is - subtly, and possibly without his even noticing it himself (if he had noticed, he would have drawn it more to our attention) - a man of the middle voice.

The formal middle voice is lacking in English. Lacking in most modern languages, actually. Icelandic has it (and arguably they need it) as did ancient Greek. It's the voice of the Campbell's soup ad, selling us "the soup that eats like a meal", the voice that lies halfway between the active and the passive. It's the voice of anyone who isn't quite sure whether it's him or them that's responsible; the voice of mournful complicity; the voice faintly heard behind Oliver Hardy's rueful accusation "Here's another fine mess you've gotten us into". Strangely (since we don't actually have it) it's the voice of the realist. The paranoiac might say "That car ran me over!" The passive submissive might say, "I was run over by that car." But the realist "got himself run over". Who knows who's to blame, but, oy, what a tsimmes. We're all in the soup together, and the soup eats like a meal.

This middle-voice world-weary resignation is inherent in who Woody Allen presents himself - or, in the films, others - as being. The recently late George Carlin raged at the idiocies of the world, demanding from his audience an eye-opening Damascene conversion. Barry Humphries demonstrates a reductio ad absurdum of our own pretensions and demands that we wet ourselves laughing.

Comedians like Woody Allen display their virtuosity because we've all had it, there's nothing to be done about it, and his put-upon schnook, in Michael Wood's marvellous - and pre-9/11 - phrase, always "looked as if a skyscraper was about to bury him, and he wanted to get a gag in before the end".

Above all, middle-voicers accept (and sometimes aggressively claim) the blame, but not the responsibility. It's the nature of the shlemiel through history. The schmendrick comes into the room and trips over the coffee-table, and the shlemiel apologises. Even when there's a possibility of getting away with it, the shlemiel doesn't have it in him. Take the end of Play It Again, Sam, with Allen playing a shlemiel saved from utter inadequacy by the ghost of Humphrey Bogart:

HIM: We both know you belong to Dick. You're part of his work. If that plane leaves and you don't, you'll regret it. Maybe not today or tomorrow, but soon, and for the rest of your life.

HER: That's beautiful.

HIM: It's from Casablanca. I waited my whole life to say it.

Others might move in for the kiss and the hand snaking up the skirt. Not the shlemiel.

Even the disjunction from reality that runs through Allen's work may be more realistic than it seems. He is by all accounts a gloomy sort of a man, except when playing jazz clarinet. (And no reason why not; nobody expects a surgeon to come to a party with a knife and an anaesthetist; why should a comedian be funny out-of-hours?) His agoraphobia is well-known. He never reads reviews or viewing figures. He claims not to know how much money his movies make. He sits in his room making it up and then, when necessary, goes off to film it. If behind the virtuosity there is simply a man in a room making it up, then art is reflecting life with uncanny accuracy. In which case, why is it - why has it been for over fifty years - funny?

Woody Allen's Mere Anarchy has just been published by Ebury Press.