This morning yet another politician was on the airwaves talking earnestly about the importance of people acquiring new skills so that they could fully play their part in the increasingly high-skilled economy. We were told yet again that the only way we could possibly compete in the modern world was by developing those very special skills which would give us an edge over the new fast-growing economies of India and China. In discussions like this it's very rare for anyone to ever ask about the exact nature of these highly desirable skills. There is a simple assumption that 'skills' are a good thing, that they should be acquired by all school-leavers (what could be worse than an unskilled workforce?) and that they should be constantly up-dated and expanded (the concepts of life-long learning and multi-skilling).

Thirty years ago we'd have had no problem explaining 'skills'. Back then a skill was a form of hard technical ability, allied with an underpinning of theoretical knowledge and understanding. A skilled worker was a cook, tailor, nurse, carpenter, builder, toolmaker, or electrician.

But today that simple view of skills has been transformed. Of course the term continues to encompass the skills that are required to be a satisfactory electrician or plumber, but most of the time it refers to something very different: it describes not so much a hard technical ability but forms of desirable behaviour. With the massive shift from manufacturing to service sector employment, new forms of skill have emerged: social, inter-personal, generic, 'soft' and aesthetic skills. As one call centre employer remarked, "we recruit attitude".

Such 'soft' skills have always been needed in some jobs. But the increasing proportion of service sector work and the perceived need for more staff to deal with 'customers', often internal to the organisation, has made them more visible and important. At the same time, management theory has stressed the need to standardise the quality of interactions between frontline service staff and customers, and to make staff contribute more to organisational success. Employers like to dignify the set of work behaviours required by this development as 'generic'. They include not only interpersonal 'skill' but also such other 'skills' as problem solving, working in teams, leadership, communications, customer handling, work discipline, and self-motivation.

That weasel word 'generic' implies that such skills can be transferred from one situation and one workplace to another. But more significantly it also implies that they can be taught to young people before they enter the labour force. But does this assumption make any sense when it is carefully examined? It may be easy enough for a school or university to instil a general predisposition to solve problems and to provide some general diagnostic tools which might make the solution more available, but many problems require very specific (often technical) knowledge to solve them.

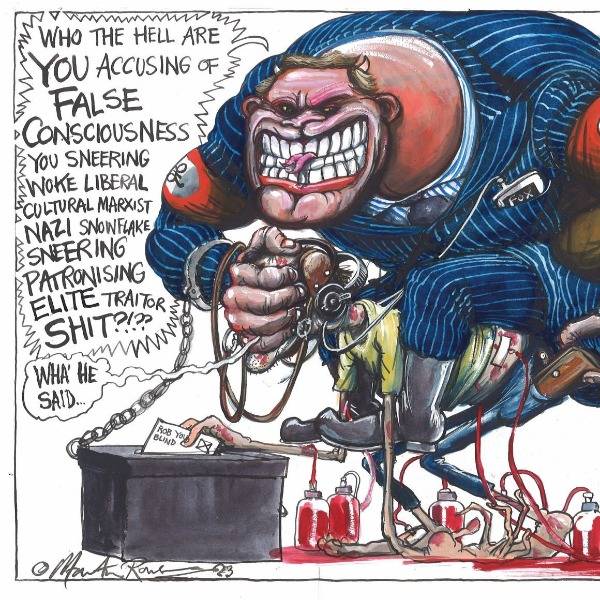

There is, though, something much more sinister about this attenuation of the term 'skill'. When we look closely at the so-called 'generic skills', we quickly discover that many of them are not what any reasonable person would ever regard as 'skills': they are, rather, personal character traits or attributes which can readily shade into the characteristics required by a employer. They are the skills which help to ensure a subservient workforce that does what it is told, and is willing to work for low pay.

Consider one of the most regularly cited soft skills: motivation. This is routinely spoken of as though it were a personal attribute that can be developed rather like muscle strength. This means that when employers say that they want the education and training system to supply them with motivated employees, they neatly remove themselves from the whole equation. They are able to blind themselves to the obvious truth that motivation is not something that is learned like geography or home-brewing or carpentry, but a condition that is created when organisations offer their staff appropriate levels of pay, good working conditions and sensitive systems of personnel management.

One neat example of how this slippage of meaning creates its own problems is provided by a survey of employers' skill requirements undertaken in central London a few years ago. Many employers complained that prospective employees lacked the essential skill of 'flexibility'. But when the survey probed into the precise aspects of flexibility which were absent, it turned out that they were a willingness to work long, unsocial hours, and to readily accept many hours of unpaid overtime.

We can hardly be surprised by the demands. Employers have always been interested in any educational development that would help to ensure a compliant workforce. A 1906 government investigation into Higher Elementary Education concluded that "what employers wanted from these more advanced schools for the children of the working class was a good character, qualities of subservience and general handiness." The difference is that in those days, no one ever dreamed of labelling such passive psychological traits as skills.

Some of the other new skills now required by employers seem even less 'skill-like' than 'general handiness'. In the last 20 years we have witnessed the dramatic expansion of what might be called emotional labour: the workers' ability to manage their feelings when dealing with customers, and in some instances, to manage the feelings of the client. No matter how bored, distracted or angry they may be, staff in call centres are told to work with 'a smile in their voice', In some instances, management literature now deems even this to be insufficient. Workers must not merely feign the required emotional response, they must be able to manage their emotional responses so as to be able to 'feel' what their employers require.

What are the implications of these developments? To begin with, the changing meaning of skill makes it harder and harder to define a job as 'unskilled'. If willingness to be flexible (work long and hard for poor pay for a bad employer) is now capable of being labelled a skill, then plainly a lot of jobs in our low-wage economy require skilled labour (about 25 per cent of the UK workforce is on EU definitions currently in low-waged employment). A corollary of this is that the traditional link between being skilled and therefore possessing a certain amount of power in the labour market that could be exploited to gain higher wages, better working conditions and more autonomy, is now also broken.

Perhaps even more alarming is the recognition that many of the attributes that now count heavily in employers' recruitment criteria could be judged to be proxies for a middle-class background. Skills such as voice, accent, deportment, and dress sense characteristically reflect the candidate's socio-economic origins and educational experience and thereby discriminate against those from lower social classes. Some academics have even gone so far as to see in this development a reason for the quite alarming news that the UK is, by international standards, currently displaying low and lower levels of inter-generational social mobility. Our new emphasis upon soft skills has afforded the middle classes an opportunity to buck the meritocratic system in which 'hard' credentials determined one's progress up the social and economic ladder.

Official debates about education and training over the last two decades have often stressed that education should meet the needs of employers, and produce entrants to the labour market who are deemed employable. How far can and should teachers and trainers go in responding to this agenda if one of the subtexts of employers' requirements is actually a demand for schooling for subservience? Should we be socialising so many of our young people into accepting low paid, dead-end jobs?

At another level, what are the ethics of providing children from lower socio-economic backgrounds with 'self-presentation' skills in order for them to be able to compete more readily in the market for aesthetic labour? This might help them avoid the costs attached to unemployment but is it really acceptable to demand that people re-engineer their own self-identity so as to conform to middle-class stereotypes and employers' demands?

A discussion of skills that ventures beyond a reflex endorsement of the latest demand from employer bodies for more job-ready youngsters is sorely needed. Cries from policy makers for more skills must be greeted with questions about what type of skills, for which people, and to what effect?

Ewart Keep is deputy director of the Economic and Social Research Council Centre on Skills, Knowledge and Organisational Performance at the University of Warwick.

New Labour

Do you have a smile in your voice, a flexible attitude and the ability to negotiate? If so, warns Ewart Keep, you could be part of a growing workforce that is skilled without necessarily being able to do anything