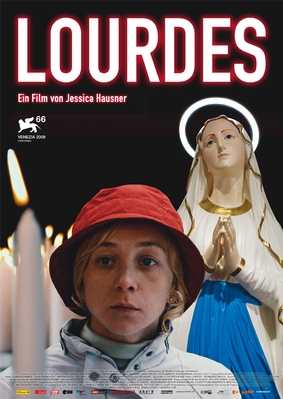

Have a look at the Rosary Basilica, a large Roman Catholic church in the pilgrimage town of Lourdes, southern France. Remind you of anything? If you’ve watched Jessica Hausner’s 2009 film, Lourdes, then the answer to that question should come easily: Disney’s Cinderella castle, the swirling chateau that prefaces every Mouse Movie, the architectural centrepiece of every Disneyland park from Tokyo to Paris. The Rosary Basilica is framed in Lourdes in such a way that the Disney parallel becomes obvious – both are surrounded by shops full of tat, neon signs, plaster cast dioramas, and worshipping visitors. Such is the quiet, smirking subversiveness of Hausner’s movie that I would be shocked if she herself had not noticed the similarities. For a seemingly serious European movie about religion (Austrian produced, French language) Lourdes has a vicious humour.

Have a look at the Rosary Basilica, a large Roman Catholic church in the pilgrimage town of Lourdes, southern France. Remind you of anything? If you’ve watched Jessica Hausner’s 2009 film, Lourdes, then the answer to that question should come easily: Disney’s Cinderella castle, the swirling chateau that prefaces every Mouse Movie, the architectural centrepiece of every Disneyland park from Tokyo to Paris. The Rosary Basilica is framed in Lourdes in such a way that the Disney parallel becomes obvious – both are surrounded by shops full of tat, neon signs, plaster cast dioramas, and worshipping visitors. Such is the quiet, smirking subversiveness of Hausner’s movie that I would be shocked if she herself had not noticed the similarities. For a seemingly serious European movie about religion (Austrian produced, French language) Lourdes has a vicious humour.

The plot follows Christine, a multiple sclerosis sufferer played by Sylvie Testaud. She goes on a pilgrimage to the holy site of Lourdes, the latest in a suggested succession of holy visits (it seems that she has met the sexy head male nurse on a previous trip to Rome). What follows is slight. Christine visits some holy sites, she watches the male and female nurses flirt, she chats with a prissy head nun. She then, amazingly, regains her ability to walk, though this by the end of the film seems to be receding again, as a doctor predicts that it will. Why does this happen? Hausner’s narrative is loathe to reveal anything. Perhaps it’s medical. Perhaps there’s been a divine swap with the nun Cécile (Elina Löwensohn), who suddenly collapses before Christine’s recovery. It seems not to matter.

What does matter is the ridiculous, the bitchy, the human. The film’s religious elements – its various church services and rituals – are opaque. High clergy and the worshipping crowd are rarely shown together in the same shot, and when they are, the faces of one party are obscured almost entirely by the body of the other. The camera, here, denies the audience any sense of connection between these two parties. Elsewhere, however, greater joy can be found in the banalities of life at the shrine: a couple of male nurses share a sacrilegious joke, brief flirtations are exchanged and, in a favourite moment, a nun leads a small congregation off to worship, her red umbrella above her in the air. She strides across the room and an automatic door sweeps open before her, as if touched by the hand of God. It’s a beautifully small, charming, stupid moment.

Balanced on the other end of this equation is the complaining and jealousy that springs forth from Christine’s “miracle”. Other worshippers either stare blankly at her, clearly wondering why they cannot be healed, and a particularly entertaining duo of women (one of whose lines, the banal ‘do you think there will be dessert?’ ends the film) do little other than bitch and moan about Christine. After long, you won’t be able to help but join in – Sylvie Testaud’s performance really is a masterclass in irritating piousness. Her post-miracle enthusiasm for life is restrained to the extent that you wonder if she’s physically able to express any kind of sinful quality – even her illicit dalliance with the handsome nurse seems somehow holy, though this is one of the film’s less convincing indulgences.

Despite that, however, Lourdes is appropriately a film of supreme restraint. Hausner resists the urge to become totally ridiculous, and she resists the urge to fetishize or obsess over the commercialisation of religion. Indeed, God remains a silent presence throughout. It’s through human urges, from the humour to the jealousy, that Lourdes gains its unique, texture. Like the man in the Mickey Mouse costume groping your girlfriend at Disneyland, the juxtaposition of human urges against the staid faces of idols makes a perverse sort of sense.

Lourdes was released on DVD in July 2010