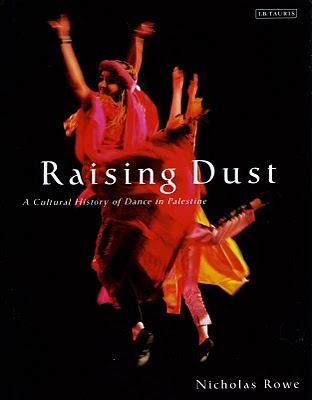

Raising Dust: A Cultural History of Dance in Palestine by Nicholas Rowe (IB Taurus)

Raising Dust: A Cultural History of Dance in Palestine by Nicholas Rowe (IB Taurus)

When any writer sits down to write anything about the Middle East, he does so resigned to the fact that he’s going to end up writing more than just that article. He will, in the days and weeks following publication, also be writing dozens of emails, mostly to very angry, occasionally downright abusive people, who will have accused him of the entire spectrum of partisan malfeasance, from Hamas fellow-traveller to Mossad stooge (these people will all have read the same article). The interminable Middle East imbroglio is like professional wrestling for the semi-educated: a heavily ritualised and grimly spectacular theatrical event about which a certain sort of person enjoys becoming sanctimoniously enraged.

Nicholas Rowe, author of Raising Dust, is emphatically not one of those people. His perspective is all the more valuable for being so unusual. He is not an activist or a journalist, still less a crusader or guerilla: he’s a dancer, who has performed with ballet companies in his native Australia, Finland, New Zealand and the Phillipines, and is now an Associate Dean at the University of Auckland. As he recalls it, his introduction to Palestine was more or less accidental. In 1998, at the invitation of Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he was attending a dance event in Tel Aviv. Curious to see what was occurring up the road, he asked some second-hand contacts to organise a dance workshop in Ramallah, on the West Bank. Here, he encountered much that made him curious, not the least of which was a woman he liked; Rowe lived in Ramallah from 2000 to 2008.

I met Rowe for the first time quite early in his stint on the West Bank, when he was running regular dance classes at Ramallah’s Popular Arts Centre. On a subsequent visit, I stayed with him and his by-then-wife Maysoun. I don’t agree with him about everything – Rowe is, essentially, and despite everything he has seen and heard, still an idealist, regarding the Middle East with patient optimism, whereas I think that if peaceful co-existence was really the dearest desire of the region’s peoples, they might have gotten around to giving it a crack by now. However, I do – as every reader should – respect Rowe’s experience of the region, and the considerable and original thought he has given its conundrums and contradictions.

Raising Dust is a good book, a lucid and interesting dissertation on it subject, illustrated with some stunning archive photographs. When you look at the black-and-white plates of dervishes dancing alongside the walls of Jerusalem’s Old City, or of a sword dance at a Bedouin wedding of the early 20th century, the chronic romanticising of the region – by the world in general, not Rowe, who remains punctiliously clear-headed – becomes easier to forgive. But much more importantly, Raising Dust is also a good thing: an all-too-rare reminder that Palestinians are first and foremost people who, as it happens, do things like dance. The greatest disservice that has been done to Palestinians – by their leaders and supporters at least as much as by their enemies and occupiers – has been the reduction of them to a cause, a geo-strategic weapon, a charity case, a guilt-trip, a reason for self-righteous grandstanding, a problem. Few of the people who agitate vociferously for the Palestinians ever trouble themselves to go and meet them.

They should, and this applies especially to cheerleaders on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian squabble. Those who reflexively defend any action taken by Israel, however cruel, disproportionate or counter-productive, will learn that not all Palestinian grievances are manufactured. Even – indeed, especially – for Palestinians who mean Israel and the people in it no harm whatsoever, life is frequently inconvenient, undignified, and worse. Rowe writes of his experience giving dance classes on the West Bank that “in almost every school and community centre that I entered, at least one local child had been killed or seriously injured by the Israeli military”. This is perfectly plausible, and utterly disgusting – (anybody thinking of writing to tell me that the Israel Defence Forces never shoot at civilians should save it for someone who hasn’t seen them do exactly that). By the same token, those who imbue all Palestinians with the untarnishable nobility popularly – though wrongly – believed to be a consequence of suffering, will learn that oppressed people are as capable as anyone else of acting like jackasses: Rowe, though his response is significantly more equable than mine would have been, recalls a dance performance in the West Bank town of Qalqilya being vetoed by local Hamas councillors, on the grounds that it flouted sharia law.

It is understandable that media coverage of Palestinians is so concentrated on the militants among them – Hamas, Islamic Jihad, the Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades and sundry ratbags are not only picturesquely violent but have unquestionable, if altogether depressing, popular support. It is ceaselessly astonishing, however, at least to this observer, that those who purport to support the Palestinian people don’t see the electoral success of Hamas in Gaza in particular as the consequence of negative reinforcement that it is: it’s a common reaction of any person or people to react to unfair criticism by becoming exactly what they were accused of being.

The homes of Ramallah, Nablus, Jenin, Jericho, Gaza and Rafah are as bedazzled by the global media as homes everywhere else. If the people living in them saw less of themselves, and we saw less of them, as victims and terrorists, and more of Palestinians as dancers (and architects and carpenters and shopkeepers and chefs and taxi drivers and various other basically decent sorts putting in a day’s work), we might all – with the exception of those deriving various satisfactions from the Palestinians’ plight – be pleasantly surprised by the consequences.