Sometime in the early 1950s Sir Alec Guinness was resident in Burgundy filming GK Chesterton’s Father Brown (1954). Guinness was playing the part of the Father, and between takes he would amble off in the local village, still dressed in costume as a Catholic priest. On one of these strolls a small boy fell into step with him and, mistaking Guinness for a real priest, took him by the hand.

Sometime in the early 1950s Sir Alec Guinness was resident in Burgundy filming GK Chesterton’s Father Brown (1954). Guinness was playing the part of the Father, and between takes he would amble off in the local village, still dressed in costume as a Catholic priest. On one of these strolls a small boy fell into step with him and, mistaking Guinness for a real priest, took him by the hand.

Guinness credits this episode with starting his conversion to Catholicism: “a Church that could inspire such confidence in a child, making priests, even when unknown, so easily approachable, could not”, he had thought, “be as scheming or as creepy as so often made out.”

This anecdote might once have been touching. Today, as new incidences of child rape continue to emerge from the cloistered world of the Catholic Church, the image of a young boy trustingly taking the hand of a Catholic priest feels almost cinematically sinister. The sky darkens; a minatory music meets the ear; won’t somebody call the police?

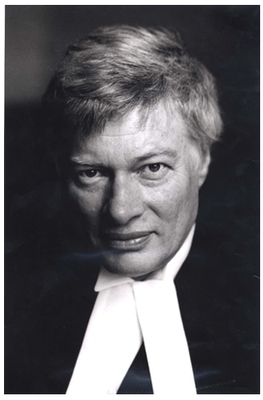

Well, won’t they? It is a question that, when you are reading Geoffrey Robertson’s astonishing (and brilliant) new book, you will have difficulty keeping from your mind. At any rate, you will have difficulty doing so when you are not struggling to assimilate the sheer scale of the abuses for which the Vatican is responsible: The Case of the Pope is so dense with affronts to honesty, humanity, and the rule of law, that one searches in vain for a passage of text that doesn’t demand to be underlined, memorised, and written down (and, yes, taken to the police). Reference to its contents must, then, be rather summary.

Extrapolating from child rape statistics from around the world (and from the predicted toll in Latin America and Africa), Robertson thinks that since 1981 the “total of molested youth in the Catholic Church . . . could well be in excess of 100,000.” In these years the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith was (until he became Pope in 2005) under the authority of Joseph Ratzinger, who insisted that all allegations of child rape be dealt with under Canon Law. Robertson shows that this “law” places child rape at about the level of heresy; endangers other children by allowing priests to be moved to different parishes or different countries; admits no scientific evidence; offers such terrifying deterrents as extra prayers or, in very grave cases indeed, laicisation; admits paedophilia as a defence against the charge of . . . paedophilia; and contains a secrecy clause forbidding any Church official from passing any information to the police, even when that official might have been party to a confession of “abuse”.

And this situation persists: the “New Norms” that Ratzinger issued as Pope in July of this year contain no instruction to report to the police priests or monks who are guilty of rape. The attempted ordination of a woman has, however, at last been recognised as a crime as grave as sodomising a child. Progress of a kind.

One of the great strengths of The Case of the Pope is that it gathers in one volume the litany of crimes for which the Vatican is responsible (a litany I have barely touched on above), offering a picture of the revolting ways in which the Church has sought systematically to cover a human rights atrocity that should, years ago, have come to light. Another of its strengths is that it forcefully dispenses with the Vatican’s claim to be a state. This claim has, quite wrongly, allowed the Church to arrogate to itself the authority to treat cases of child rape under Canon Law; but it has also helped the Holy See to promote its vile ideology of misogyny and homophobia at the UN, where it often finds itself in alliance with Libya and Iran, and where it likes to obstruct programmes for the distribution of condoms to those affected by HIV and AIDS.

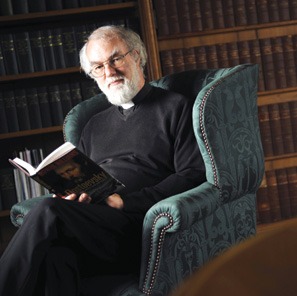

When I visited Geoffrey Robertson at his Doughty Street chambers I asked him why he had written the book. “I wrote it out of a sense of shock, I think, at Easter of this year, when I looked at the evidence of the incidence of child abuse in the Catholic Church. And although, I guess like most people, I’d seen stories here and there, in America and a bit about Ireland, it hadn’t hit me just how enormous this human rights atrocity was and that it hadn’t been recognised by Amnesty International or anyone else as a human rights atrocity . . . so the evidence drove me, as a lawyer, to see this, really, as a crime against humanity.”

Robertson wonders at the close of his book how the Church has so far “escaped international censure” for these crimes. One explanation, he suggests, might be that its good works have endowed it “with an aura of goodwill that protects the Holy See from condemnation”. I wonder if there might be other forces at play. Has reticence to condemn the Church anything to do with the privileged status that religion is accorded generally? Is part of the problem not the assumption that religious institutions deserve “respect”, or are assumed to be models of probity because religion tends idly to be equated with morality?

Robertson wonders at the close of his book how the Church has so far “escaped international censure” for these crimes. One explanation, he suggests, might be that its good works have endowed it “with an aura of goodwill that protects the Holy See from condemnation”. I wonder if there might be other forces at play. Has reticence to condemn the Church anything to do with the privileged status that religion is accorded generally? Is part of the problem not the assumption that religious institutions deserve “respect”, or are assumed to be models of probity because religion tends idly to be equated with morality?

“I think we are, and the human rights community is, perhaps over tolerant of religious excesses. I think we need to define more carefully exactly what religious freedom, the entitlement of the religious, is. It’s certainly to have a spiritual life, and to live a spiritual life in a way that is joyful or comforting, however much it may be the result of fear of death, but we must make it clear that it has to be compatible with the rule of law and with consideration for other people. So that, in the case of the Pope, we have the most egregious church, one that claims to be a state, and hence immune, operating its own law, its Canon Law, and making the fundamental mistake of dealing with a serious crime as if it were merely a sin. There is no punishment under Canon Law. The Pope only a couple of days ago said Canon Law is perfectly satisfactory for the child abuser. It is not. It’s a medieval process, all in writing. No cross-examination to test the truth. No forensics. No sex offenders register. And no punishment!”

The Pope clearly bears a huge burden of responsibility here. For most atheists protesting the Papal Visit, this probably isn’t a difficult idea to assimilate. It must, however, be much more disturbing for Catholics to accept, which perhaps explains why Robertson is concerned to convince them of the severity of the crisis and of the profound culpability of their Pope. “My book is aimed at the intelligent Catholic. I work with a lot with Catholic organisations against the death penalty and, in Africa, against HIV, AIDS, and so forth, and I know how concerned they are that this abuse scandal will reflect on them; will mean less donations for work that is good. So I’m coming from a slightly different perspective than the secularist one. And I really feel, quite frankly, that this is so great and deep a crisis, as the head of the Belgian church said recently, that there’s no easy way out. The only decent and dignified way is for Benedict to resign.”

If such a thing can be imagined, it would be essential, wouldn’t it, that the proper reasons for his resignation were given? The hysterical secrecy with which the Catholic Church has, throughout its history, conducted itself, suggests that the possibility of this is extremely remote. “Yes. And the fact that his resignation is beyond belief says, I’m afraid, a great deal about the Cath . . . about the Vatican and about him.” This small self-correction is characteristic of Geoffrey Robertson: cognisant of the good work done in the name of the Catholic faith, he takes care to distinguish between the Vatican, Catholicism, and religion more generally. In some ways this tendency is admirable, but I wonder whether there is a danger in assuming that the offences perpetrated by the Church originate in the corruption, rather than the nature, of religious belief.

I ask about a passage in his book in which he states that “the Catholic Church will never, I suspect, release its hold on the very young or understand that this is the real reason for its sex abuse problem.” Shouldn’t our concern here be with the role that religious belief plays in allowing that hold to be established? The idea that there is such a thing as divine authority; the idea that there exists a God who demands to be feared and loved; the idea that there is such a thing as eternal torture (an idea that is, remember, introduced by the supposedly moral figure of Christ); these are fundamental to Christianity, and they are the ideological weapons with which the priests secure precisely the hold you describe.

“Yes, I agree this is a particular concern. It is the fact that children are indoctrinated at the age of seven into first of all communion, where the priest is the agent of God, the miracle worker who transforms the bread and the wine into the body and the blood; and then they go to confession, where the priest is the terror figure. So, unflinchingly, they obey the priest. And when the priest says turn over, and when the priest says ‘trust me, I’m a priest’, they trust him and they don’t complain. And when the priest says ‘if you tell you’ll burn in hell’, they don’t tell.”

What does he make of the Vatican newspaper campaign to reduce the age of first communion to five or six? “I think that is very serious and has to be stopped. If the Catholic Church is serious about child abuse it will not inflict upon its children this utter belief that the priest is God . . . I mean I think the existence of so many paedophile priests is a pretty good argument against God. If his own agents are so despising of one of Christ’s most emphatic rules, about not affecting children . . . ” Although they drive home quite assiduously the rule about eternal torture . . . “Yes. In fact I make the joke that they made a very curious qualification in accepting the UN Torture Convention, which seems to allow torture to continue in hell. I quote Cardinal Newman of course. It struck me that the reason that he gave for converting was that Catholic priests were so absolutely good and never erred. Of course, I don’t think Newman would be converting to the Catholic Church today.”

Our interview is drawing to a close, so I ask Geoffrey about the rather deflated note on which his book ends. What is to be done next in the attempt to bring the Pope to account?

“I think if there was a second edition of the book – you have to remember that this edition was begun at Easter and went to press in early August – its closure would be rather more forceful. The more I think about it the more I think the solution has to be the Pope’s resignation. I think I would probably write a couple more paragraphs making the case that he really has to resign. This scandal will not go away until something concrete is done.”

As I tramped up Gray’s Inn Road, I found myself doubting that something concrete would ever be done. The Pope lacks both the shame and the dignity to resign. The possibility of a trial is slender. It is a near certainty that cases of child rape will continue to be “tried” under Canon Law. Meanwhile, as atheist and secular outrage at the depravities of the Church gathers in volume and intensity, the Church lowers itself more deeply into the cauldron of absolutism and impunity that it has occupied for so long. Its unlovely descent does not mean that secularists and atheists should keep their silence; but it might be that the real burden of protest lies with the Catholics of whom, and for whom, Robertson writes so passionately in his book. I am unaware of the grounds upon which a Catholic is able to reject the authority of an infallible leader who is the Vicar of Christ on Earth. But to make such a protest would be to take a stand for justice; for truth; for the rule of law; and for equality of human rights. To make such a protest might even help lay the foundations of a priesthood in which someone felt able to call the police.

The Case of the Pope is published by Penguin