If there’s someone on your radio right now telling you there are no big ideas in politics any more, or that our risk-averse society is lowering ambition and infantilising adults, or that the outpouring of anguish over Darfur says-more-about-the-anxieties-of-the-western-liberal-elite-than-the-realities-on the-ground, there’s a good chance they’ve got something to do with an organisation called the Institute of Ideas.

If there’s someone on your radio right now telling you there are no big ideas in politics any more, or that our risk-averse society is lowering ambition and infantilising adults, or that the outpouring of anguish over Darfur says-more-about-the-anxieties-of-the-western-liberal-elite-than-the-realities-on the-ground, there’s a good chance they’ve got something to do with an organisation called the Institute of Ideas.

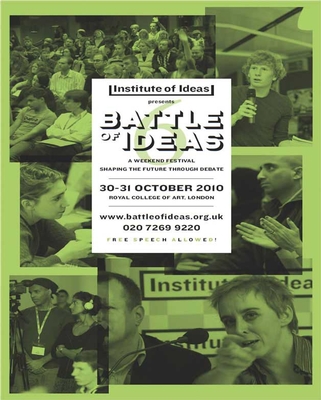

The Institute’s purpose, according to its founder, Claire Fox, is to “interrogate orthodoxies and debate the challenges facing society, and to make these things public activities”. It does this in the face of “politically correct etiquette” and an “illiberal liberalism” which “silences genuine public challenges to received wisdom”. The IoI’s annual debating festival, the Battle of Ideas (sponsored by Shell, The Times, Price Waterhouse Coopers and brewing giant SAB Miller), is a “public square within which we can explore the crisis of values”. The Festival “is very much a PUBLIC conversation”. Its motto is “FREE SPEECH ALLOWED”.

When a coalition of humanist, secular and equality groups rallied against the Pope’s state visit to Britain earlier this year, the IoI issued a press release (PDF) describing itself as a “leading British humanist thinktank”, denouncing the “hysterical” arguments of the Vatican’s critics and accusing “fellow-secularists” of conducting a “New Atheist witch-hunt”.

The Institute of Ideas has a close, if ambiguous, relationship with the online magazine Spiked, an outspoken scourge of environmentalism whose memorable slogans include “Bomb the Bans” and “Humanity is under-rated”. Both are orphan children of the magazine formerly known as Living Marxism (subsequently LM), which went bankrupt at the turn of the decade, following a disastrous libel defeat. Both are dominated by ex-members of the UK’s long-defunct Revolutionary Communist Party. Spiked contributors regularly feature in the Institute’s debates, and the magazine often echoes IoI concerns. Ahead of the Papal visit, Spiked ran articles attacking the reaction from secularists, including New Humanist, as a “fear-driven campaign of demonisation”.

Critics have accused the Institute of Ideas and Spiked of knee-jerk contrarianism, of empty sloganeering, of trading the garb of the far-left for that of hard-right libertarians, of being guided more by the interests of their corporate sponsors than by any coherent underlying philosophy.

But whatever else one thinks, Spiked and the IoI have a talent for getting noticed. Claire Fox gets a weekly slot on BBC Radio 4’s Moral Maze discussion programme. Spiked’s “editor at large”, Mick Hume, has a regular column in The Times. The Institute of Ideas is active in UK schools, as is a related organisation, Worldwrite. Whole websites have been devoted to tracking the influence of ex-RCP figures in the UK media.

So what kind of humanists are they? Do they have a genuine commitment to open debate or is this just a rhetorical conceit? And who’s really defending the legacy of the Enlightenment? I went along to this year’s Battle of Ideas festival to try to find out.

I should declare some interests. I work for a human rights organisation, have friends who were involved in the Pope protests, and am broadly sympathetic to environmentalism. Spiked gave my last book a duff review, and I’ve said flippant things about them on my blog. I went to the Battle of Ideas bracing myself for a live hybrid of Spiked and the BBC’s Moral Maze, which is to say that I wasn’t expecting much. I was pleasantly surprised by what I found.

The debates I saw were lively, upbeat, impassioned and well-attended. The audiences seemed strikingly diverse both in terms of age and social background. While most of the panels were chaired by (or featured) someone connected to the Institute of Ideas, the debates felt like genuine discussions which allowed space for a range of views.

Among the most heated was a set-piece entitled “The Catholic Church: More Sinned Against Than Sinner?”. This pitted eloquent Catholic campaigner Austin Ivereigh against the equally impressive US civil liberties activist Wendy Kaminer, together with Catholic-born law professor (and Spiked contributor) John Fitzpatrick and Peter Cave of the Humanist Philosophers’ Group.

Ivereigh’s thesis, echoing Spiked, was that the anti-Pope protests were a classic case of scapegoating, led by white, middle-class, middle-aged atheists, and that this reflected a “crisis in secularism”. Kaminer countered that it was absurd to paint the Church as a victim, given its vast wealth and power. Humanist groups were puny and impoverished by comparison, and surely posed no great threat.

Fitzpatrick, who described himself as both a Communist and a Catholic, was visibly angry, condemning the demonstrations as “a carnival of conformity and intolerance”. He’d been particularly incensed by Richard Dawkins’ description of the Pope as “a leering old villain in a frock”, and the Church as a “profiteering, woman-fearing, guilt-gorging, truth-hating, child-raping institution”.

“You have to start asking not about the Catholic Church but about the people who are demanding silence and conformity in spiritual and political and intellectual opinion. The people who say ‘we will arrest you’ if you don’t conform.”

Fitzpatrick had attended mass at his local church earlier that day, and “what people were talking about there ... it’s about love, it’s about helping asylum seekers, it’s about campaigning for minimum wages, it’s about getting together to discuss and uphold those values.” He simply didn’t recognise the picture that the Church’s critics had painted.

The audience piled in, with opinion seemingly divided evenly. One speaker from the floor, a “Commie Marxist Leninist” involved in the running of abortion clinics, had been outraged by the “illiberal and intolerant” reaction to the Pope’s visit. She attributed this to a “crisis of the liberal intelligentsia”. She’d been more outraged still that her inbox had been bombarded with “Protest the Pope” emails, seemingly in the assumption that she’d be on-side.

Another moving contribution came from a mother of three who’d once been a “very passionate Catholic”, but became increasingly alienated from the Church over “the shaming of our bodies”. She had joined the Protest the Pope demonstration and found it “very diverse”– nothing like its critics had described.

I came away feeling that there had been caricaturing on both sides of the discussion. To portray a peaceful protest as a “witch-hunt”, however heated the rhetoric, feels patently absurd. To explain away a whole movement in terms of some vague “crisis of liberal values” seems to depart from reality even further.

Yet I’d also seen something of the human side of the ex-RCP, even if I was still in the dark about the basis of their humanism. These were not merely knee-jerk contrarians. Fitzpatrick and his erstwhile comrades were righteously pissed off.

I moved on to a very different debate, this time about the role of peer review within science. It was a good-natured and at times quite technical discussion. Tracey Brown of Sense About Science gave a characteristically robust account of why the peer-review process matters (“yes, there is an alternative – it’s called patronage”). Dr Richard Smith, former editor of the British Medical Journal, made the surprising claim that a peer-reviewed review of the peer-review process had found no evidence that the system did much good.

It was an intriguing suggestion, but also one that highlighted the limitations of trying to evaluate complex issues through live debate. Short of sitting with a laptop and Googling every claim, it’s difficult to analyse what we’re being told in the way that we could with a book or a written article. To a large extent, we’re at the mercy of the panellists to interpret the technical details for us, and it’s difficult to avoid taking some things on trust.

If there is a crisis of liberal values, then no one seems to have told Evan Harris, the former Lib Dem MP and secularist champion, who shone against Spiked’s Natalie Rothschild and the Telegraph’s Bruno Waterfield (formerly of Worldwrite) in a debate on “burkha bans” and “B&B bigots”. But the finale of the day came with a panel discussion on “Optimism versus Pessimism”, featuring (among others) Claire Fox, Mick Hume and the writer Marcus Sedgwick.

Fox talked passionately about the value of political debate. Hume, introducing himself as a “grumpy old Marxist”, spoke of Gramsci’s notion of “pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will”. He got grumpier still when Marcus Sedgwick cited the success of the whistle-blowing website Wikileaks – a seeming bête noire for the ex-RCP old guard – as a reason to feel optimistic. Claire Fox was quick to take his side. It was the first really sour note of the day, and the conversation felt a bit stilted from then on.

It was at moments like these that the anti-establishment rhetoric seemed to ring most hollow. While Mick Hume clearly still sees himself as an orthodoxy-busting radical, his views on Wikileaks could just as well have come from any other Times pundit. Claire Fox, these days, can be hard to distinguish from her fellow Moral Maze panellist, the arch-conservative Melanie Phillips.

And while the IoI’s success in securing corporate sponsorship is in many ways admirable, it’s difficult to believe that the likes of Shell and Rupert Murdoch would stump up to support an organisation that they felt threatened their particular brand of “orthodoxy”. I was struck by the number of times a speaker declared themselves an Old Marxist, whilst standing against a giant backdrop covered in capitalist branding.

I’d sat through a head-spinning eight hours of debate, and come to the following conclusion: shibboleths aside, these people are the real deal. Whatever it is they believe, they seem to believe it sincerely. But I still didn’t feel much closer to understanding what the core of those beliefs was. And I still couldn’t shake the sense that there was more going on than was immediately apparent.

I did a lot of Googling. I looked through old editions of Spiked, LM magazine and Living Marxism. I contacted some people who could loosely be described as ex-RCP/IoI insiders. All wished to remain anonymous.

“I think you can talk about an organised group of colleagues who work together to forward a coherent ideological project,” one told me. “They have a very consistent and strong agenda which all of the various groups promote in different ways ... there is some fairness in the charge that they are not as open as they could be. There may be some paranoia within the organisation regarding being thought of as an insidious network, so I think they play down these very close links.”

I came across an intriguing quote from Dolan Cummings, a former RCP member and co-founder of humanist civic freedom group the Manifesto Club, writing in 2007: “I never left the RCP: the organisation folded in the mid-’90s ... few of us actually ‘recanted’ our ideas. Instead we resolved to support one another more informally as we pursued our political tradition as individuals, or launched new projects with more general aims ... These include Spiked and the Institute of Ideas, where I now work. It must be said that this development annoyed our political opponents immensely, and a cursory Google search ... will return a plethora of exposés purporting to show that former members of the RCP are involved in various sinister conspiracies. In short, even in its afterlife, the RCP remains as controversial as [Islamist group] Hizb ut-Tahrir ... the impossibility of simply doing away with a school of thought that is no longer attached to an organisation is perhaps what annoys our opponents most of all.”

Looking through the archives, one theme that seems particularly strong is an unshakeable empirical belief in the ability of the human race to triumph over adversity, and progress, through science and technology – combined with an equally firm moral belief in the imperative of our doing so for the greater good of the species. Alongside this is a fear that we will fall short of our potential if we seek to impose limits on ourselves, or set our expectations too low. This appears to be what sits behind Spiked’s hostility to environmentalism, and its arguments for seeking to mitigate climate change through technology, rather than trying to prevent the problem by cutting back on industrial activity.

My own difficulty with this brand of super-humanism is that it feels very much like a faith-based position. Where some may place their trust in God to shield civilisation from the predicted effects of climate change, Spiked and the Institute of Ideas seem to have cast their lot with human ingenuity. I hope they’re right, I really do, but given our mixed track record as a species, it seems like something of a leap in the dark. What does a humanist do when reason leads us to question our faith in human potential? ■

Spiked-o-babble

From cycling to recycling, health and safety to binge drinking, the Institute of Ideas and Spiked never miss an opportunity to bait liberal sentiment. Here are a few of our favourite headlines.

Crusade against the pope: an Inquisition-in-Reverse – The campaigners against the pope’s visit have more in common with the fanatical Inquisitors of old than with Enlightened liberal humanists (Frank Furedi)

A futile intervention into our drinking habits – Just because excessive alcohol consumption can have medical consequences, that doesn't make it a Medical Problem (Dr Michael Fitzpatrick)

Oh god, not another Greenpeace guilt-trip – Green advertising campaigns are aimed at scaring adults witless and turning kids into Mao-style mum-policing spies (Rob Lyons)

A ‘cycling revolution’? On your bike, Boris – When cyclists are continually told that their mode of transport is saving humanity from doom, it’s no wonder so many of them are annoying pricks (Brendan O’Neill)

This shutdown is about more than volcanic ash – The flight ban is a product of officialdom’s apocalyptic thinking, where they always imagine that the worst-case scenario will come true (Frank Furedi)

An oily, underhand demand for censorship – Calling for ExxonMobil to stop funding climate-sceptic groups is really a demand that these groups be silenced (Rob Lyons)

The British elite prefers polite Malthusianism – The American woman paying British drug addicts to stop breeding is only saying out loud what respectable people normally say in code (Nathalie Rothschild)

Al-Qaeda supporters on campus – so what? – If there’s one place where people should be tested and provoked by all sorts of ideas, it’s the academy (Tim Black)