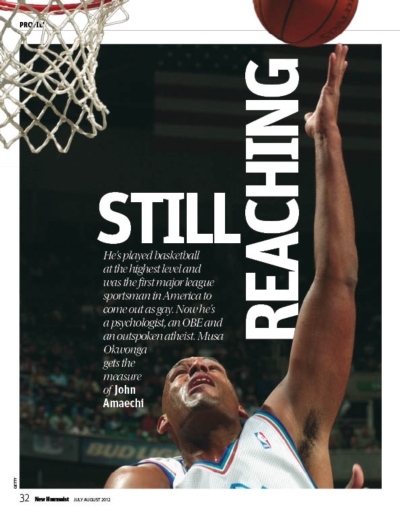

John Amaechi is many things. First of all, he’s vast. As I walk into the lobby of the central London hotel for our morning interview, I see him in the corner of the lounge, waiting patiently with a coffee; as he rises gently to his feet, it is a wonder that the chair was capable of containing him. A former professional basketball player – over a 12-year career he played for several European clubs and in the American NBA for the Cleveland Cavaliers, the Utah Jazz and the Orlando Magic – Amaechi is not far shy of seven feet tall. Though his physique is more imposing than most, many of his life’s challenges have required strength of the mental kind. He was born in Boston, where he lived until his English mother, having been left by his Nigerian father, brought him to Stockport; there he grew up with his two sisters. He returned to America aged 17 as a high-school student. He went on to become the first athlete in any of America’s major league sports to admit openly that he was gay. After retirement in 2007 he returned to the UK to study and promote sport to disadvantaged youth. He began a PhD in clinical psychology and, in 2011, received an OBE for his services to sport and the voluntary sector. In between all that, he found time to start a business and a charitable foundation.

John Amaechi is many things. First of all, he’s vast. As I walk into the lobby of the central London hotel for our morning interview, I see him in the corner of the lounge, waiting patiently with a coffee; as he rises gently to his feet, it is a wonder that the chair was capable of containing him. A former professional basketball player – over a 12-year career he played for several European clubs and in the American NBA for the Cleveland Cavaliers, the Utah Jazz and the Orlando Magic – Amaechi is not far shy of seven feet tall. Though his physique is more imposing than most, many of his life’s challenges have required strength of the mental kind. He was born in Boston, where he lived until his English mother, having been left by his Nigerian father, brought him to Stockport; there he grew up with his two sisters. He returned to America aged 17 as a high-school student. He went on to become the first athlete in any of America’s major league sports to admit openly that he was gay. After retirement in 2007 he returned to the UK to study and promote sport to disadvantaged youth. He began a PhD in clinical psychology and, in 2011, received an OBE for his services to sport and the voluntary sector. In between all that, he found time to start a business and a charitable foundation.

It’s been difficult for many people to keep track of everything that he does; whoever wrote his Wikipedia biography tried their best, describing him as a “a psychologist, educator and political activist”. What does he think of that? “I’m not a political activist,” he replies. “I think that’s just a cop-out for people who’d want to be able to say, ‘Ohhh, he’s one of those people. He’s an agitator.’ Which is what that really means. And I am not. I am controversial, but not because I want to be. Most of the debates I’m involved in I’m not even remotely interested in being involved in.” He gives a somewhat surprising example.

“I don’t care about gay people in sports [coming out],” he says. “I care about people in sports who are gay. But even this issue is so small [compared] with the issue of young people killing each other, and underachieving in schools, because of persecution and the perception of a hostile environment. It’s embarrassing to me that people spend time talking about how a man who makes £35,000 a week is feeling about being in the closet.”

He has equally little time for the terminology that often accompanies advocacy for gay rights. “I don’t recognise the idea of ‘gay marriage’,” he tells me. “I think it’s a ridiculous term. I recognise marriage equity. I don’t know what that is.” He is irritated by the label ‘gay’, particularly since it is often used with negative connotations to describe anything ineffectual. “I don’t understand how the bonding of two people who love each other to give them legal protections and political and public recognition – which is what marriage is – becomes gay; in the same way that I don’t understand how a computer that stops working becomes gay. I don’t understand how a pencil when it breaks becomes gay. People say that about all those things, but it doesn’t make it true.”

Amaechi’s body language is one of the most interesting things about him; it’s calm and self-contained, his gentle manner belying the passion of his words. Even when at his most forthright, he rarely raises his voice. He accepts how he may he perceived with equanimity. “I’m difficult,” he says, “and I make no bones about that. I’m very polarising – some people like me, some people hate me. I don’t care, it’s not relevant. But people who have needed me to be a certain way have experienced that. So there will be children and young people and adults who have had harsh interactions with me that were necessary, at least in my estimation.”

Consistent with his empirical outlook on the world, Amaechi is an atheist, and as such rejects the idea of an afterlife. “It’s just so crazy. The delusion is just ridiculous,” he says, although this is not the language he would use of someone suffering bereavement. “I think it’s cruel to tell a six-year old, ‘Your mother’s gone, she’s never coming back, and there’s nothing of her left.’” He prefers a different approach: “Tell her that her body’s gone, but she lives in your memories, and every time you talk about her, you are stoking those memories – keeping those alive in you, taking nourishment, sustenance from those memories. That’s what I do. But telling them that in 60 years, when you die, you’ll be able to meet your Mum again? How is that even useful, telling someone that they’re in a better place? If they’re in a better place, why don’t you all just go now? This place is far from ideal, but this is the best we’ve got. So it’s about how we deal with this now, rather than, in the back of our minds, thinking the world is temporary.”

He gives the example of his mother, who passed away several years ago. “I love [her], and if you asked me who I would spend a day with if I could it would be her, but the idea that my life is meaningful because one day I’ll be reunited with her? I mean, she would be so pissed off. She would be furious at me even endorsing such a ridiculous view.”

I ask whether Amaechi, when coming out as a gay man, had experienced a period of mourning that he would not be leaving his genes behind. “Oh God, no. No, no, no. [As for] people who think that the genetic part of having children is the most important bit, that’s a bit of an anathema to me. I don’t disparage it, I just don’t understand why that would be important.” But isn’t his legacy important to him?

Key to Amaechi’s legacy will be his openness about his sexuality, which caused a stir when he announced it in his 2007 book Man in the Middle and which many thought might open the floodgates for other athletes to come out. So far, though, there has been no such deluge. The Wales rugby union player Gareth Thomas recently revealed that he was gay, but his example is a rare one. Which of the major leagues in the UK and US, I wonder, would be most receptive to an openly gay player?

“Probably the National Basketball Association and the National Hockey League,” he replies. “They’re the only leagues where the bosses – the actual commissioners and many of the owners – have said, ‘Look, this should not be an issue.’ But people don’t seem to realise that they don’t operate in a vacuum. They operate in a context – in America, for example – where it’s still legal to be fired in 30 states for being gay. So there’s no point in pretending, when there’s active discrimination going on right now, that they would be safe. What happens when they drive home? What happens when they get married, or want to get married to their partner? What happens when they want to have children? What happens?”

He is now focused on his work for Amaechi Performance Systems, his consultancy that helps individuals and organisations to improve their effectiveness. He works with independent and public schools in the US, where it appears that his legacy partly consists in building a new generation of leaders. “We work with independent schools because these people are going to be the most powerful people in the country. Take Taft, for example, an independent school on the East Coast of America, 30 per cent of the current US Senate come from Taft.” What of schools in the UK? “It’s a hard market to penetrate,” he admits, “because they don’t want to change.”

Given his concern for young people, I ask him about the challenges that they face in the UK. “The reality is that the experience of young people nowadays, through school, through hard life, is to make them emotionally illiterate, to make them socially stunted. It just creates people who are unprepared for the world.”

He points out that government policies, most recently the Coalition’s austerity measures and raising of tuition fees, have aggravated the problem. “And there’s the other element,” he continues, “which is the question ‘What is the point?’ I talked to a teacher the other day and I said, ‘Look, there’s no point you talking to me about how you want young people to work hard to get their GCSEs, because the real question is: can you answer the question “what is the point?” And you can’t answer that question at the moment, because I can tell you by postcode how much a [two-year-old] kid in London will make when they are 30.’”

“One of the big problems with going to university,” he adds, “is that it doesn’t take into account privilege. It doesn’t take into account that if you come from a certain type of area, the idea of taking on debt, while daunting, makes sense for the delay of gratification. But if you come from another type of area where, say, your younger brother is getting sucked into a world that maybe you’ve been smart enough to pull yourself out of, and this could be your escape, are you really going to take on that debt? Knowing that if you don’t take on that debt, maybe your brother can come and live with you in a different area? These factors are just not taken into account.”

These, he says, are issues that politicians would really rather avoid. He doesn’t seem like the type to dodge a difficult subject, though. Perhaps he should consider a career in politics? “The only way I’d go into it – and it sounds pompous – would be in the House of Lords,” he says. “I would absolutely do that in a heartbeat. I was very much dismissive of it, but then my friend Tanni Grey-Thompson became a Baroness, and I saw what she did, single-handedly galvanising the Lords against the reform of benefits. And I thought, wow. It’s one thing to barter from the sidelines … There’s also the title of Lord – I mean, I’m surprised by how much legitimacy my words have now that I’m an OBE.”

Lord Amaechi has a ring to it, I suggest. “Yes, it does,” he says, mulling over the idea with some amusement. “Quite terrifying, too: you think I’m going to come in with my shield and spear,” he says with a smile. Medieval costumes aside, it is an honour that he would welcome. “I would very much enjoy [being a Lord]”, he says, unembarrassed. “I enjoy being big. I enjoy that it gives me presence and power. I enjoy every additional thing that gets loaded on, like the OBE, and the degrees, and whatever else gives me more power. But I use them wisely, because I remember what it was like to be powerless.”