“Kill or be killed: the Commune also, the Commune which writes on its banners such elevated ideas, knows this old law of the sword”.

“Kill or be killed: the Commune also, the Commune which writes on its banners such elevated ideas, knows this old law of the sword”.

This is Victor Serge, writing in 1919, from a pamphlet called Revolution in Danger designed to convince anarchists and libertarians to support the Bolshevik Revolution. It’s an unusually honest piece of propaganda. The man who wrote it was an obscure functionary and journalist, who has gradually been rediscovered as a chronicler of revolution from the inside, and a revolutionary thinker. Once only feted by the intellectual cognoscenti – Susan Sontag was a fan – he is now gaining a wider public, to the point where Nicolas Lezard can declare in the Guardian that “anyone who cares about justice and freedom of speech” should own a copy of his memoirs.

Serge confronted, in his frequently banned, confiscated and slandered writings, the usually fudged questions thrown up by violent social change; as old, he acknowledges, as the English Civil War or the French Revolution. How do you defend a revolution from the armed resistance it will inevitably provoke, while maintaining its humanist principles? And after you’ve chosen violence and repression, how do you know when to stop?

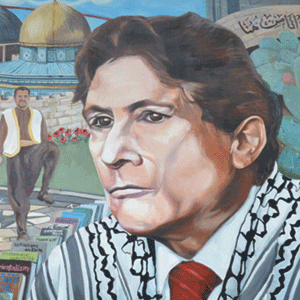

“Victor Serge” was the pen-name of Victor Kibalchich, born in Brussels to Russian refugees, revolutionaries on the run from the Tsarist secret police. He grew up in dire poverty, and was educated at home by his parents, in an environment where “the portraits on the wall were of men who had been hanged”. In Paris and then Barcelona he became an active anarchist. Deported from France in exchange for anti-Soviet hostages, he threw himself into the apparently far-from-libertarian Bolshevik Revolution, even defending – albeit through gritted teeth – the suppression of the semi-anarchist Kronstadt uprising of 1921. He became a Comintern agent, working abroad in Berlin and Vienna, before returning to the Soviet Union, where he joined Trotsky’s Left Opposition.

Expelled from the Communist Party, he was deported to Siberia in 1933. He got out in 1936 through luck, on the eve of the Great Purge – his reportage and novels, written in French for a French audience, made him well-known enough to be embarrassing for a Soviet government then trying to court the liberal intelligentsia. He returned to France, fleeing the Nazis in 1940 and escaping to Mexico, thanks to the intercession of American intellectuals like Dwight Macdonald. There he wrote exposés of Stalinism and novels “for the desk drawer” and died, as poor as he had begun, in 1947.

His work was rediscovered by the New Left of the 1960s, and then forgotten again. His militant revolutionary politics meant that he never renounced Communism as a “God that failed” yet his insistence that the Russian experience should be critically revised from start to finish placed him beyond the pale for most Trotskyists. Meanwhile his defence of the Bolsheviks’ use of terror alienated him from his former anarchist comrades and all but the most outré liberals.

What is now in print in English comes from tellingly different quarters. Serge the Communist is represented by a far-left organisation – the British Socialist Workers Party (SWP) publish his defences of Bolshevism, such as Revolution in Danger – while Serge the humanist sceptic is published by the liberal literary press – the New York Review of Books’ Classics have recently reprinted his dark, hallucinatory novels, and now a complete text of his Memoirs of a Revolutionary.

You might think this reflects a man who writes different things for different audiences – a fraud – yet Serge’s work is remarkably, amazingly consistent. His fragmented, personal, morally complex and utterly urgent style rings through in his propaganda sheets and reportage as much as in the late novels and memoirs. In Revolution in Danger, surplus to its agitational purpose, there are descriptive passages of striking literary quality, animating the tense atmosphere of revolutionary St Petersburg/Petrograd on the eve of civil war, where on the opulent boulevards the workers and the bourgeoisie pass each other, fully in the knowledge that they will soon have to kill each other. He writes of the atrocities and pogroms of the anti-Bolshevik “White” armies, and depicts something often now overlooked – the role of direct democracy in the Revolution, including its somewhat less “idealistic” aspects. Writing up a meeting of the local Soviet in 1919, he notes that “if, later on, the newspapers in London and Paris accuse [the Cheka – the secret police, the precursors to the GPU, NKVD and KGB] of being responsible for the Red Terror, they will be lying. I saw terror voted by acclamation by the people of Petrograd, coming up from the streets, freely, at the point of danger.” Yet in the same texts he outlines how he expects the new state to develop when the war is over, as something voluntary, democratic: “centralisation, agreed, but not of an authoritarian type. We may have recourse to the latter from necessity, but never from principle. The only revolutionary form of organisation is free association, federation, co-ordination.” But to get to that, quite different means had to be used.

Writing about the same period, in the 1943 Memoirs, he explains his support for the Bolsheviks, as against the anarchists and Mensheviks who it might seem were his natural allies. One of his vivid, quick sketches: he remembers the anarchists of Petrograd in the Civil War, defending the offices of Pravda, “the Bolshevik paper they hated, ready to defend it to the death. They discovered two Whites in their midst, armed with hand grenades and about to blow them up. What were they to do? They locked them in a room and looked at each other in embarrassment. ‘We’re jailers, just like the Cheka!’ They despised the Cheka with all their hearts. A proposal to shoot these enemy spies was rejected with horror. ‘What, us to be executioners!’ Eventually, they let the two White conspirators out altogether. ‘I was a fool, wasn’t I?’, he asked me. ‘But you know, all the same, I’m glad of it.’” Serge admires their heroism and consistency, but is aghast at what happens when the anarchists attempt to fight a civil war while maintaining principle. He finds the anarchists of Moscow considering an anti-Bolshevik rising, and deciding against it because they wouldn’t know what to do about the famine then raging in the Russian countryside.

By the time of the 1946 novel Unforgiving Years (recently republished by NYRB) he appears to reject this weighing up of means and ends. He has “D–”, an NKVD agent, resign in protest against the Nazi–Soviet pact. He listens to a horrified comrade, who he recruited to the service, try to convince him to stay, and “the old spool unwinds by itself: that every apparently abominable deed perpetrated corresponds to a necessity, since they are perpetrated, that the Party, led by supremely capable hands, stands over whatever it does, that if we start to doubt we’re doomed, that those who are killed – that YOU YOURSELF taught me all this!”

In the face of this, he feels “a liberation difficult to justify”. At the same time Serge continued to justify his version of the Russian Revolution, with the new proviso, as he writes in the Memoirs, that revolutionaries “never give up the defence of man against systems whose plans crush the individual”. At the back of this, you can be sure, he remembers he had once written that the Bolshevik Revolution would lead to “the great rebirth of humankind”.