This penetrating study of the effects of childhood neglect focuses on one brilliantly drawn character: Sir Edward Feathers, sometimes called Teddy or Eddie, but better known as Filth - an acronym for Failed in London Try Hong Kong. Having made his career in the Far East as a clever barrister and respected judge, Filth returns home to retire and to reflect on the emptiness of his life. The narrative deftly intercuts between different stages in Teddy's life: his painful, stuttering childhood hemmed in with secrets; vivid glimpses of boarding school, at which Gardam always excels; his troubled adolescence and early sexual encounters; near death on a refugee boat during the War; his curious billet in the West Country, protecting Queen Mary in her evacuation. Then there are the long years in the Far East with his dependable wife Betty, and his cathartic reaction to her sudden death.

Teddy is a Raj child in the days when tiny infants were packed off to the home country, seeing their parents only every few years. He is endlessly abandoned by his mother who dies giving birth to him in Kotakinakulu province in Malaya; and by his father who, wretched with grief, refuses to see him until he is five and about to be sent to England in the care of a missionary.

Teddy is wrenched screaming from the arms of his young nurse Ada, whom he adores, and begins what is to be a lifetime of curtailed relationships and broken links. He is placed in a grim foster home with three other children who have been billeted by their expatriate parents, all affected differently but permanently by the cruelty of the appalling Ma Didds.

After Betty's death Filth feels impelled to seek out two of these fellowsufferers, his distant cousins Babs and Claire, as if by rediscovering painful memories he can expiate them.

The theme of emotional amputation, revealed in darting flashbacks and abrupt time shifts, is charted through recurrent images of plants and trees. Babs keeps plastic flowers in water. Queen Mary, who loathes sentiment, is obsessed with pruning and especially hates ivy.

Betty's guilty set of pearls, given her by a long ago lover, slip into the holes she has made for the tulip bulbs at the moment she dies. The passing on of her remaining jewels becomes a central concern of the story for Teddy underlines his fractured relationships through gifts.

He has nothing left of his parents, and no one to inherit his own possessions. The Feathers had no children because Teddy's own ugly childhood has stoppered any desire to repeat the horror. "Children are cruel. They are wreckers of the soul," he tells Vanessa, Claire's daughterinlaw. "Betty knew we must not have a child because of the child I was myself."

Betty's jewellery is passed to the unencumbered Vanessa, who in one of the novel's rare glimmers of redemption, names her first child after Teddy. Babs and Claire have both rejected the bequest. Like Teddy, they are unable to sustain connections because, as Babs says of Raj children: "We're all touched, one way or another."

Some survive, most are scarred. Some remain victims and others become oppressors. As Albert Loss, Feathers' curious alter ego, remarks carelessly: "I suppose you know that there are those who believe that endurance of cruelty as a child can feed genius?" Loss's real name is Albert Ross, which is why Eddie wryly dubs him Coleridge. True to the reference, he triumphs by cannibalising others. Not only does he take Teddy's watch his only remembrance of his father but, more significantly, his address book. He strips him of his identity.

Teddy comes to regard himself as incomplete because he believes life is given meaning by memory and desire. His overprecise memory is no use to him because he is unable to feel real desire. The mother figure he worshipped as a schoolboy was incapable of love. All along he is haunted and paralysed by the agonisingly revealed secret guilt which has suffocated him throughout his life.

Even his confession told reluctantly to a priest, despite his wariness of any religious salvation is an anticlimax as he realises his mortal sin wasn't anything like as momentous as he had believed.

This is a marvellously rich and textured story, alive with potent characters and vivid descriptions of privation and adventure. The writing is punctured with exquisite images that weave together the personal stories and their wider backdrop. The father of the house where Teddy is staying at the outbreak of war throws a white eiderdown out of a window in a rage: "Eddie could make out the square shape of desecrated satin lying up against the house like a forlorn white flag."

And when Filth finally returns to Hong Kong after years of exile, "as he made to leave the plane, a black misery suddenly came upon him like the eye bandage slapped around the face before it is presented to a firing squad."

Beneath the glittering saga and the dazzling language of this remarkable novel is a savage, angry account of the lasting legacy of cruelty: how the damage suffered in childhood can never be repaired.

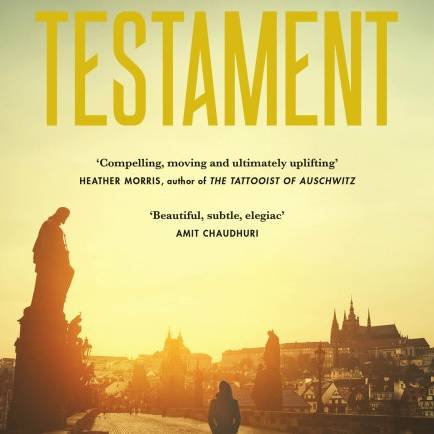

Old Filth is available from Amazon (UK)