I grew up in the Northern Ireland of the 1970’s, a child of the troubles and the peace movement. My first word was ’splosion, my first grown-up argument with a Religious Education teacher and my first political act a boycott of a Scripture Union kids club. Religion has always fascinated me and my childish and definitive reaction against it is something I am trying to consider in a more adult way, by writing a play about it.

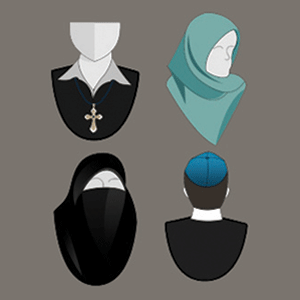

After I left the National Theatre I created a theatre company to explore fundamental preoccupations of contemporary life. The company is called On, as each piece of its work is on a given subject and because the pieces produced are more like theatrical essays than conventional plays. We produce one theatre essay a year and have made pieces exploring love, death and how the brain constructs a sense of self. This year, in this time of moral unease, of fundamentalisms, of Allah and Jesus and veils and threats, the piece could only be On Religion.

The theatre has always struck me as the best art form to explore human issues because it is the art form of the human scale. It’s about persons and their relationships to themselves and others and their surroundings. And when I make a theatre essay I try and begin the creative process in the most human way, through conversation and meetings. My first meeting was with my now co-writer, the philosopher AC Grayling. Given my background it’s hardly surprising that I had been drawn to his critique of the ‘religions of the book’ but, more than this, it was the clarity of his writing that I admired. And I was intrigued to see if a collaboration could actually work between a theatre maker like myself, whose business it is to put human life in all its grubby contradiction on show, and a philosopher whose fundamental trait was precision of argument and thought.

Clearly more people had to be spoken to. Grayling and I in different ways had spent most of our adult lives criticising organised religion so how could we even begin to imagine that we could put an authentic religious voice on stage? Did we even want to? Research would tell us. We decided to interview people who had spent a large proportion of their life thinking about religion, from well-known commentators like Rowan Williams and Giles Fraser to Lewis Wolpert and Richard Dawkins, from Muhammad Yusuf Al-Husseini and Tariq Ramadan to John Gray and Alistair McGrath. And we talked to ordinary people, religious and non-religious, asking them the same question: What does religion mean to you?

Some of the words of our interviewees have found their way into the script. One has even become the basis of a character – and that, I’d like to say before he sees it, is the greatest form of flattery possible – and the play begins with an opening image provided by Richard Dawkins. When rather cheekily asked what he would do if he himself had a religious experience, he replied, “well, I’ve just attempted to”. What? He had just been to Canada to visit a neurologist who is experimenting with inducing religious experiences electro-magnetically. Candidates wear the God helmet, as it’s nick-named, and wait as a series of magnetic charges are administered. And? “It didn’t work on me.”

So now we are asking the characters in our play the same question: what does religion mean to you, Grace – a 60-year old woman, a professor of science and a committed atheist? “I am not an atheist.” Sorry, Grace, a committed humanist. What does it mean to her husband Tony, an unreconstructed lefty Jew who says he doesn’t give a shit about it, but had their son circumcised? And what does it mean to their son Tom and to the young men who will blow him and themselves to kingdom come?

We don’t know yet and we’re still struggling. Can you imagine how difficult it is for a clear-minded philosopher to have his on-stage representative telling lies and behaving badly? Can you imagine how fascinating it is to write an articulate, sensitive, well-educated character who finds liberation and release in genuine religious inquiry? But it’s slow and painstaking work, taking people seriously.

Luckily we’re not struggling alone. Actors and stage designers are now involved as we write and rehearse our theatre essay. And though arguments are still raging and differences of taste and clashes of styles are still causing tensions, most of it is now on the stage. I don’t know how it will all end up. I doubt On Religion will come to many splendid conclusions but we hope that the play will give its audiences a space for independent thought and reconsideration as it gently asks: what does religion mean to you?

On Religion played at the Soho Theatre in December 2006