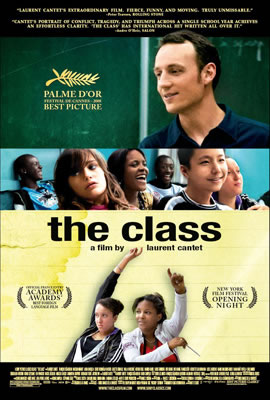

There's something very theatrical about school; not just in the way in which the classroom mimics the audience and performer relationship of the theatre, but also the way in which every participant of the day's drama - teacher and student - is putting on an act of their own, whether that's grandstanding in front of their peers or pretending that they really care if someone is using a mobile at the back of the classroom. It's worth noting, then, that the large majority of actors in The Class play, if not themselves, then characters whose name they share - it can be hard to tell where the actor stops and the character begins. The film follows, roughly, a single school year, in which Mr Marin (played or, rather, relived by François Bégaudeau, the author of both the screenplay and the book upon which it is based) teaches his class French language and literature. Some pupils misbehave, others thrive, one is forced to leave, and another joins. The final shots of abandoned chairs, flung across the room, bristle with potential energy, and although drama emerges, the film never ceases in its message: the same circumstances will be repeated year after year, replete with all of their flaws and their innovations. The brilliance of The Class is its depiction of the abnormalities that occur in an otherwise mundane cycle of events.

There's something very theatrical about school; not just in the way in which the classroom mimics the audience and performer relationship of the theatre, but also the way in which every participant of the day's drama - teacher and student - is putting on an act of their own, whether that's grandstanding in front of their peers or pretending that they really care if someone is using a mobile at the back of the classroom. It's worth noting, then, that the large majority of actors in The Class play, if not themselves, then characters whose name they share - it can be hard to tell where the actor stops and the character begins. The film follows, roughly, a single school year, in which Mr Marin (played or, rather, relived by François Bégaudeau, the author of both the screenplay and the book upon which it is based) teaches his class French language and literature. Some pupils misbehave, others thrive, one is forced to leave, and another joins. The final shots of abandoned chairs, flung across the room, bristle with potential energy, and although drama emerges, the film never ceases in its message: the same circumstances will be repeated year after year, replete with all of their flaws and their innovations. The brilliance of The Class is its depiction of the abnormalities that occur in an otherwise mundane cycle of events.

The school itself is unremarkable. The buildings are modern and characterless, the rooms cluttered and untidy but not dirty. Mr Marin is not a Robin-Williams-as-John-Keating inspiration, nor is he a tyrannical Ed-Rooney-as-Dean-Jones. His worst pupils show promise and his best pupils giggle at the back. Almost everyone is suspiciously normal; The Class is several steps away from being an "issue" film in the same vein as La Haine, and is all the better for it. Yet, despite the normality of the classroom and its characters, drama appears on the smallest level, growing organically over the course of the year. And, regardless of the inherent theatricality of school, the film is anything but stagy; the camera focuses insistently on the smallest details - the gum chewers, pen droppers and note passers. It is acutely aware that, on the fringes of the story that it tells, other unknowable narratives are unravelling. Yet these stories are kept firmly at the fringes. The Class never so much as ventures (except in a single shot at the start of the film) outside the boundaries of the school. Beyond those confines, information about the pupils' fates and the teachers' private lives is denied, creating a film in which the audience embodies the building itself. The French title is, typically, a little more incisive than its English translation; Entre les murs means, literally, 'between the walls'.

The Class does, however, have issues, one being its length. At over two hours it could be twenty minutes shorter. Its average scene is too long, despite the fact that a shortening would, perhaps, remove the slow but satisfying experience of watching plot slowly emerge from the most prosaic of situations. The other, less excusable problem, is one of stereotyping. The Class laudably refuses to make an issue out of tensions that occur in the mixture of races making up a Parisian high school. Indeed, more of its ire is directed toward the divisive nature of football fanaticism (you can tell that it was written by a teacher). It does, however, slip up in its depiction of Wey, an Asian student who is - yes - quiet and - yes - plays videogames.

The Class is focussed, almost obsessively so, on its subject and this is its greatest quality, but it also results in its few failures. It can be riveting and beautifully ironic. It can, too, be dull and unfair; rather like being at school.