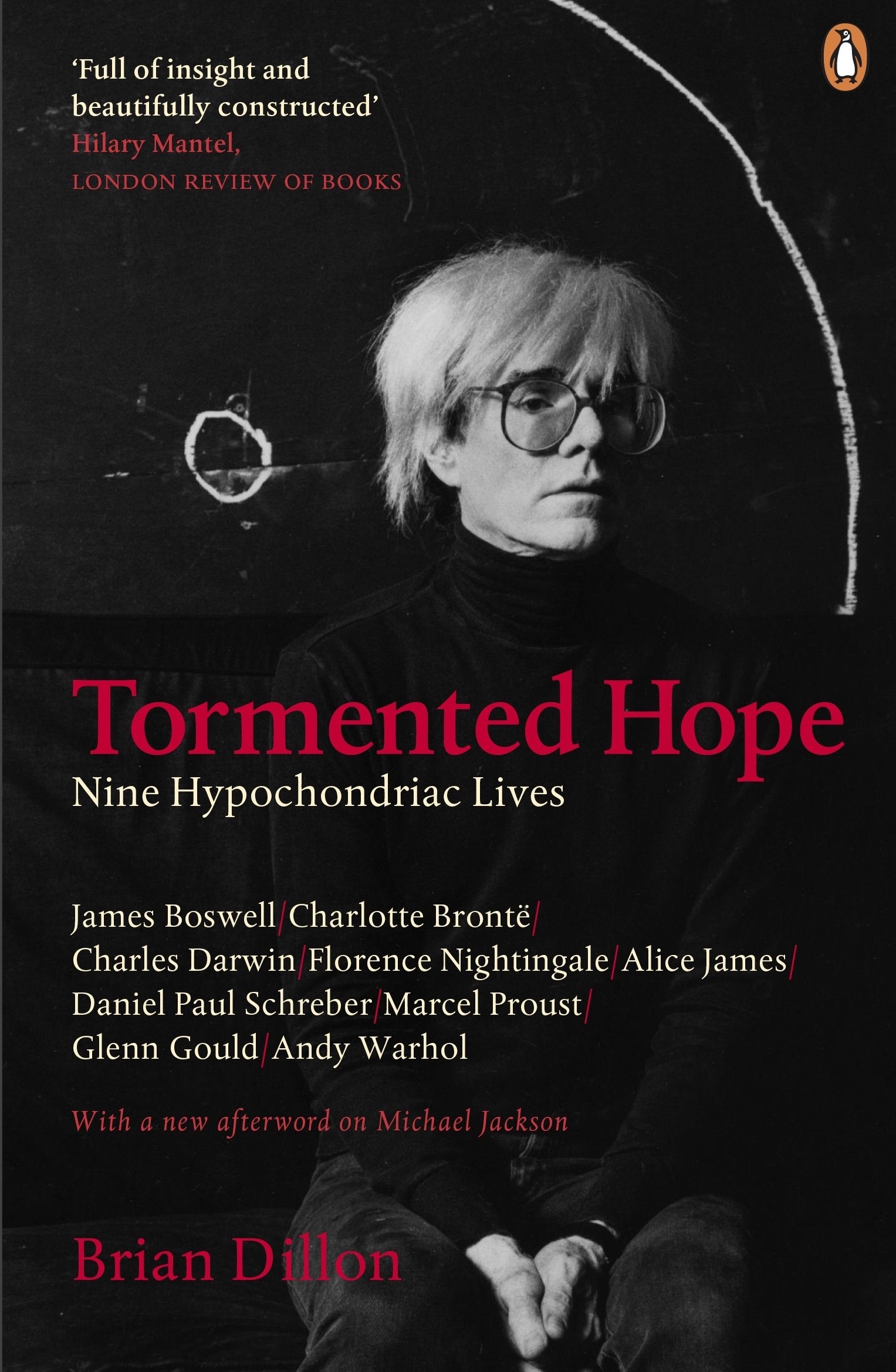

Tormented Hope: Nine Hypochondriac Lives (Penguin Ireland) by Brian Dillon

This book is very heaven for those of us captivated by the peculiar workings of our bodies, who secretly read the medical dictionary when we were kids. I was fascinated by ours, terrified and enlightened by it. A paperback crackling with fragility, rescued from a fire on Liverpool Street Station, its cover barely discernible, the page-edges blood-brown. It looked sick, smelled bad, and personified and confirmed my worst fears about human vulnerability.

Brian Dillon has written a terrific book on hypochondria that really hits the right nerve. It wriggles under your skin with absolute precision despite the many theories of what hypochondria might be, and the different sensations the hypochondriac might experience. Classical medicine, still current in the 18th century, knew hypochondria as a general term for diseases affecting the digestive system, which in turn affected the whole body. As Coleridge put it in his warning against hubristic scientism, “Doctors are shallow animals; having always employed their minds about Body and Gut, they imagine that in the whole system of things there is nothing but Gut and Body.” Eventually, post Freud, hypochondria acquired a psychological, and often pejorative, meaning: Freud suggested that hypochondria was a form of narcissism, “the state of being in love with one’s own illness”. Hypochondriacs were at best mistakenly fearful of the smallest bodily changes, at worst delusional and welcoming of diagnosis and death as confirmation of their very real, debilitating anxieties.

Among the nine hypochondriac lives here, all thinkers and artists, are three women, though most sufferers were once assumed to be male - women were thought pathological creatures anyway, and most nervous diseases allegedly affected over-sensitive “brainworkers” - for which, read “on the whole, men”.

James Boswell had a plan, an inviolable plan, to help him overcome his dread of “dissolving”. He waged a mental and physical battle with torpor: “You was [sic] pitiful and wretched”, he admonished himself. Early rising, vigorous exercise, regular dining and sex helped. He wrote over 70 articles in The London Magazine as “The Hypochondriack”, claiming that writing was the only real cure. Charlotte Brontë, too, understood that her intense frustration at the precious little time she could spend writing brought on a “kind of depression and an apprehension of the worst”. And Darwin had to regulate his working day to accommodate his bodily antagonisms, diligently recording his state of health (the gradations of flatulence, particularly). Theories abound as to the causes of Darwin’s discomforts, from insect bites to iatrogenic disease aggravated by arsenic. Whilst Florence Nightingale’s “studied enfeeblement” was supremely useful, providing her with space and time to work, her experiences at Scutari surely gave her an overwhelming insight into miserable human frailty.

Hypochondriacs have an ambivalent relationship with medicine and doctors. Fixed, or transfixed, by the medical gaze, Alice James’ peripheral life was reduced but finally validated by a diagnosis of a palpable, terminal disease. Surrounding oneself with the paraphernalia of illness both guards against and invites the worst. Marcel Proust practically buried himself alive in his own bedroom, where even the specially prepared walls appeared to affect his breathing, and where he eventually died. The frail, spectral Andy Warhol had an utter dread of doctors and hospitals, and Glenn Gould, the eccentrically glamorous pianist, whilst a big fan of prescription drugs and medical technology, succumbed to terrible self-neglect.

Dillon’s account of Daniel Paul Schreber, who wrote a memoir of his condition and was the subject of a study by Freud (who never actually met him), is most unnervingly good. The extraordinary Schreber believed that he had been chosen by God to give birth to a new race of men and was slowly changing into a woman – his hypochondria not only encompassed his corporeal self but had a cosmic element. His body became mutinous and alien: he believed his stomach would disappear during meals and his legs fill up with food and drink. The perceived fragility of, and betrayal by, one’s own body can be terrifying and isolating.

This is a tragicomic book, of bizarre beliefs, regimes and remedies undertaken because of real suffering. Add to this the fallibility of doctors, from when they knew they had little to offer the sick except platitudes, when medical knowledge progressed one funeral at a time. Today the medical profession seems hardly any better trusted, despite the extraordinary advances, occasionally because of them. Nervous diseases, such as hypochondria, are arguably metaphors for socio-economic decay, so Dillon’s book is of its moment – “health anxiety” being all too familiar to us now.