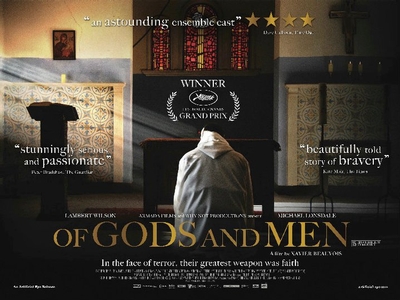

Xavier Beauvois directs an almost exclusively male cast in Of Gods and Men, the dramatisation of the murder of 7 Trappist monks by Islamic Extremists in Algeria, in 1996. Watching the film, it is easy to see why it did well at this year’s Cannes Film Festival. You can almost hear the snarls of appreciation from the audience. Peter Bradshaw described it as a film of "high seriousness". Oh, God.

Xavier Beauvois directs an almost exclusively male cast in Of Gods and Men, the dramatisation of the murder of 7 Trappist monks by Islamic Extremists in Algeria, in 1996. Watching the film, it is easy to see why it did well at this year’s Cannes Film Festival. You can almost hear the snarls of appreciation from the audience. Peter Bradshaw described it as a film of "high seriousness". Oh, God.

One scene in particular that has caught the attentions of the critics has been the penultimate congregation of the monks, imaginatively dubbed “the last supper” by many. Here the monks, having decided to await their likely deaths in the monastery, gather for a meal, while their doctor, Luc (Michael Lonsdale, also known as the evil Hugo Drax in Moonraker), plays for them a tape recording of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake.

Critics are split as to whether this scene is manipulatively sentimental or a triumph of emotion. I was reminded of the end of Andrei Rublev in which, after several hours of stark black and white photography, the film gives way to burning colour stills of Rublev’s icon paintings. Here, a movie whose soundtrack has been dominated by stern Cistercian and Gregorian chants follows these up with a balletic overture that sounds like pop music by comparison. It is a moment of which only cinema is capable.

Indeed, it is a beautiful sequence and an important one because it is the ring pull on the tin of the film's deeper message. Through this scene we can open up the entire film, its questionable take on religious devotion and its gnawing narrative problems.

Whether or not Of Gods and Men is a religious (as opposed to a film that takes religion as a subject) is unclear before we get to Swan Lake. What that scene shows us, as the tears roll down the grooved faces of these ancient monks, is that Of Gods and Men is a film of human concerns, but one that fails to address the deep seam of manipulation that runs through its subject matter.

The Algerian liberation fighters are largely absent, seen only in a few key scenes. They are, however, the ever-present threat, and their religious motivations are widely debated by the characters, with the general conclusion being that they are misguided, used by earthly interlocutors, in a word, manipulated by their religious leaders.

Alongside this is a central debate between the monks, conducted in between their chores, surgeries and rituals: should they stay or should they go? To stay is to almost certainly be murdered. To go is to, well… it’s not clear. Their leader – firmly in favour of remaining – is Brother Christian, played by Lambert Wilson. Wilson looks rather like a classic Hollywood bad guy, and I spent some portion of the film waiting for him to announce that if the monastery began to travel below 50 miles per hour, it would explode. His most well-known role (apparently) is that of Merovingian, in The Matrix trilogy. No? Me neither. The Wikipedia page on the character gives some insight into just how deep the bullshit goes on that one but, ultimately, his character in Of Gods and Men is more full of rubbish than a fictional computer programme could ever be.

Right in front of our eyes, Brother Christian plants a seed of faith in the minds of his doubting peers, leading them to the conclusion that they should remain in Algeria to face certain death. Their decision is depicted neither as heroic, nor as foolish. This should be commendable – a straight-faced display of fact, brushing aside allegorical temptations. Even the two monks who survive the final assault are judged not as cowards, nor as cleverer or more sensible than those who are murdered.

However, in a film that clearly addresses the issue of religious manipulation in elements of the Muslim community in mid-90’s Algeria, it is shocking that Brother Christian’s machinations are questioned only by French bureaucrats and soldiers, who are all depicted as unemotional brutes.

There is a gap here between faiths, their leaders, and the seeming absence of any deity to provide guidance. Of Gods and Men is a beautiful, moving work of cinema that is frequently shocking, sometimes for the wrong reasons.