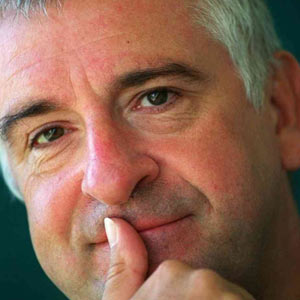

Just off the Boulevard Michelet, in the south of Marseille, lies Le Fair Play, a toilet of a drinking establishment in which even the furniture looks as if it wants to leave, and the proprietor responds to the mildest of enquiries with near-theatrical impatience. My girlfriend and I are drinking “rustic” red wine from glasses the size of egg cups, and a few hundred metres away, like some giant technicolour radiator dumped on a set of partially submerged stilts, stands Le Corbusier's Unite d'Habitation, the building in which Jonathan Meades now lives with his wife, Colette, and in which we are to spend the night to talk about his remarkable career.

Just off the Boulevard Michelet, in the south of Marseille, lies Le Fair Play, a toilet of a drinking establishment in which even the furniture looks as if it wants to leave, and the proprietor responds to the mildest of enquiries with near-theatrical impatience. My girlfriend and I are drinking “rustic” red wine from glasses the size of egg cups, and a few hundred metres away, like some giant technicolour radiator dumped on a set of partially submerged stilts, stands Le Corbusier's Unite d'Habitation, the building in which Jonathan Meades now lives with his wife, Colette, and in which we are to spend the night to talk about his remarkable career.

For 40 years or more, Meades has worked as a restaurant critic; as a cultural, literary and architectural journalist; as a novelist; and as a broadcaster. An avowedly “superstitious atheist” (the allusion to Browning is characteristic of the allusiveness of his talk and work in general), he can be provocative, tendentious, original, intelligent, dry, belligerent, ironic – and, when it suits him, doggedly literal (the sky being the place “where God lives, with his beard obfuscating his irate face”). He has covered an extraordinary array of subjects. Yet in almost all of his work there exists an abiding love of and preoccupation with place and what makes place, and a concomitant interest in the ways in which a proper understanding of place displaces the claims of the theistic.

When Meades welcomes us into his elegant home, I recognise only traces of the persona – brash, hostile, impudent, derisive – with which viewers of his films for television will be familiar, and instead I find a gentle, humorous and reflective figure who, as we move upstairs to his study, is in the mood to talk. Our conversation lasts for some time, and touches on numerous subjects: “Tony Blair needs his head seeing to. I think Blair needs shooting, actually. One hopes that with the Olympics some of the security around him will have to go off and he and Cherie can end up as the Ceausescus of Connaught Square.” If you’re going to start your own religion, “go for more mumbo jumbo, not less mumbo jumbo. You want lots of silly dancing, clapping, ‘God’s a great guy! God’s a great guy! Jesus! Jesus!’. You need all of that. You don’t need something sophisticated, which is why fundamentalist happy-clappies in former Scout huts in Peckham have done so well.” But we spend most of our time talking about his childhood, his intellectual formation and the roots of his hostility to belief.

Meades was educated at Salisbury Cathedral School (“where they didn’t have doubt”) and later at the King’s College in Taunton (“Chapel twice a day was fucking terrible. This place was very unacademic. It was about making gentlemen of the local tradesmen’s kids, and Devon garage-istes, and Cornish pasty farmers (or whatever they do with pasties: ‘I’m going to grow a field of pasties, but I’m going to do it with a posh accent.’ That’s what it was about. It was a grotesque place. Horrible.”) He remembers “a very philistine kind of Anglicanism” reigning at the Salisbury Cathedral in the ’50s, promulgated by an “incredibly snobbish clergy” who were “very, very snobbish about my parents, because my father didn’t have his own business. He was a rep for a biscuit company, and that was kind of beyond the salt, or whatever the expression is, and they somehow knew that my parents didn’t go to church. They were kind of spinsterish. Even if they were men.”

In one of the three books on which he is currently working, An Encyclopaedia of Myself (“it’s actually not about myself. It’s about my parents’ generation, from the perspective of a child, and the child is a kind of camera, watching these people. I’ve been re-reading it, and it seems to be a book about suicide and death, drinking yourself to death, boorishness, bitterness, anger”), such clerical spinsters acquire the sinister lasciviousness that tends to attach itself to the self-consciously sex-denying. “There’s nothing in the book which is invented,” he tells me. “For the most part I try to keep a distance, and just look on with a sort of neutrality, which in some cases is quite difficult, when you’ve got your father’s friend putting their hands in your lap, and a cast of extremely dubious paedophiliac prep-school masters hanging around Salisbury Cathedral Close.”

It was while he was surrounded by these figures that Meades discovered his love of place. As a boy – sometimes with his father (who was “always fishing”), but often alone – he would spend hours visiting the rivers, water meadows and canals around Salisbury (“I was a tireless pre-pubescent cyclist, which stopped me masturbating”). These excursions furnished him with the realisation that most of what he saw around him in the supposedly natural world was not natural at all, but man-made. There was and is, as he likes to phrase it now, “nothing natural about nature”. Meades speaks of these kingfisher days in his rather affecting film Father to the Man, and remarks that it would be preposterous to claim that his interest in the man-made world, in “mankind’s interventions”, was an augury of incipient humanism. But his antipathy to “the God malarkey” did, he says, have its roots in what was obviously made.

“I was brought up in the epicentre of the earliest inhabited area of Europe. And this is all around you. Everywhere there are barrows, tumuli ... There is so much around there, and it’s so rich, you’re constantly – or I was constantly – being made aware of it, from a very young age. That this landscape, so much of this landscape, had been created by man rather than geological happenstance. It hadn’t just happened. It was made like this.”

It was, as he phrases it in the same film, our intelligent design. Yet these childhood experiences, in which a “midget autodidact from the planet Pig Ignoramus” went out to learn about the world for himself, were not, he tells me, the prelude to a loss of faith. “I’ve been writing about this. I didn’t have any faith to lose. So I denied myself the adolescent crisis of faith. It just didn’t happen! Because I didn’t really believe in anything at all. I still don’t believe in anything – I don’t really believe in atheism. You don’t believe in atheism. I’d prefer to be an agnostic, I’d prefer to believe in doubt. But it’s an area in which it’s pretty difficult to have any doubt. To believe in God strikes me as being like believing that the Earth is flat. I think there was an excuse for it; I don’t think there is an excuse for it now. I think really anyone who practises religion should not be allowed to hold public office, because, as David Hume said, they’re suffering from sick men’s dreams.”

Hume is never far from Meades’ lips when he is discussing religion, the subject that, more than any other, seems to incite his anger. “I’m hostile,” he tells me when I ask why this should be so. “I’m not particularly angry. Well, no. It does anger me. What angers me is the special pleading, and this idea that there can be no morality without religion, which I think is absolute balls. Complete balls. I think it’s the other way round. I can’t see that religion does anyone any good whatsoever. I am hostile to it, though I don’t like the preachiness of a lot of anti-religious stuff. Dawkins has become just like a vicar.”

Of the many aspects of religion – especially of English Protestantism – that attract Meades’ anger, he reserves a special hatred for its attitude to sex and death. “Sex and death” are, he writes in Museum Without Walls, “kept apart from life.” There is an imperative to “pretend they don’t really happen”, and the theistic monopoly on the whole business of human expiration very often, too often, results in a denial of choice for those secularists who are about to become post-secularists, posthumous secularists. So treated, “The dead are denied choice. The dead are other, they have no rights. They are obliged to submit in this culture to one of two means of disposal, and to do so quickly lest they embarrass the still living.” I ask him to elaborate:

“As regards death, just at the lowest level, Protestant funerals are infinitely to be avoided. And I think secular services or celebrations or remembrances or rememberings, or whatever you like to call them, are so much better. Both my parents had Christian burials. My mother was talked into it by a vicar, and I did find offensive at both my parents’ funerals the way in which it’s all about God. It’s not about the person who’s died. You know: Jesus wanted this, you’re doing this in the name of the Lord, the name of the spirit, the name of the fucking Trinity. Secular services are very good, the ones I’ve been to. There is a kind of grace about them, because it is about the person who’s died, rather than about this institutionalised fiction. It’s offensive, the way that it gets brought into something which is so potentially emotionally harrowing as a funeral, and obviously one of the problems with death is that it is shunted away now. The Victorians wouldn’t talk about sex, but God, they would talk about death. And that has been completely reversed. We can’t face death.”

During the course of our conversation it becomes apparent that, for Jonathan Meades, that last statement is, emphatically, untrue. “Do you think about death?”, he asks me. “I think about death absolutely every single day of my life. Have done for as long as I can remember.” And with his saying that, I remember the piece in Museum Without Walls, where he writes that, when he dies, he would like to be “mounted, stuffed”, and “subjected to benevolent and verisimilar taxidermy”. Is this really how he wants to look, adrift on the eternal prize cruise? “Yeah. I want to be stuffed. A better job of stuffing than Jeremy Bentham, I would hope. More like some kind of very high-end Pharaoh. In a nice glass case somewhere. But the trouble is, no one wants me. None of my daughters wants to be saying, ‘Oh, that’s Dead Dad in the corner.’ Not keen on the idea. I quite like the idea of just being put on a tip somewhere. And I certainly don’t want anyone to spend money on a coffin.”

Jonathan Meades on France is currently showing on BBC Four, and can be viewed online on BBC iPlayer. An Encyclopaedia of Myself by Jonathan Meades will be published later this year by Fourth Estate