“Epidermal leaks!” I’d exclaimed when she first gave me the news over meringues in Patisserie Valerie. “How horrible. Who’d want to hang around with anyone who suffered from epidermal leaks? Imagine. ‘This is my friend, Laurie. He has a leaking epidermis.’ I don’t think so.”

“Well, you did ask,” said Janet with all the calmness of someone who currently spends three days a week patching up marriages in the Friern Barnet area.

“I was making conversation,” I told her. “Chatting. I wasn’t asking for a clinical assessment.”

“You were. You told me that you repeatedly found yourself in situations where someone or other would notice that bits of your past life were showing through. You told me that only last week one of your old friends had noticed that you were sounding more and more like an old Stalinist.”

“Old Trotskyist. I was a Trotskyist. Not Stalinist. Trotskyism was totally opposed to Stalinism. It recognised that the Soviet Union in its later forms had nothing to do with socialism or communism. It was state capitalism.”

“Whatever. And then you told me that last Sunday you’d been walking past the Italian Catholic church in Clerkenwell and felt your right arm give an involuntary twitch as though it was starting to make some sort of sign.”

“Not some sort of sign. The Sign of the Cross. ‘In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.’ Or ‘in nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti’: the same sign that the priest does with his finger on the baby’s head during Baptism; the same sign that the priest does on the forehead of anyone who’s dying when they’re giving Extreme Unction.”

“Whatever. That’s two occasions when your body has betrayed you. Two occasions when your rationalist demeanour has been punctured by ideas and emotions from the past. Two epidermal leaks. But, hey, who’s counting?”

“Go on,” I said, now submissive. “Tell me about epidermal leaks.”

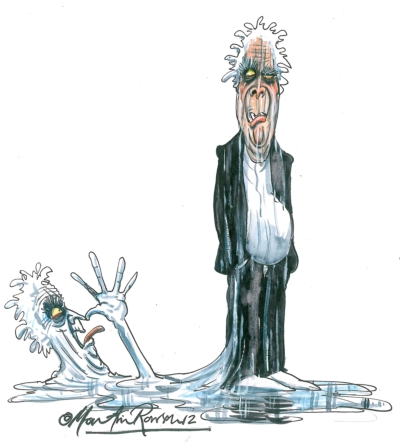

“Well,” said Janet, with an assurance that must surely have worked wonders with the squabbling adulterers of North London, “when we are very young we all suffer from epidermal leaks. Our bodies deny the truth of what we are saying. Think of young children trying to lie or to pretend that they’re not tired. Their bodies betray them. Then think of an expert adult poker player. Even though they may be bursting with emotion, there is not a sign of it on their faces, on their skin. They are epidermally sealed. Leak-proof. But when you get older you lose this capacity to keep yourself to yourself. As your real skin gets thinner so does your psychological skin. You constantly start to betray yourself. You lose self-control. Your decorum wilts. Your sense of tact atrophies.”

I didn’t really need to listen to any more. I could suddenly remember other shaming examples of this lack of control. There’d been the recent evening at the Pizza Express jazz club in Soho when I shouted out, “Play that thing” to a bemused avant-garde tenor saxophonist, that nasty moment on holiday in Cornwall when I’d tripped as I scrambled over the rocks and heard myself shouting out for Mummy, the time I’d burst into uncontrollable sobbing during an episode of Animal Park when a young lion cub was kicked out of the family den because the mother had a new litter. “Look, he’s all alone.”

Could Janet offer any advice? Was there any way I could repair these epidermal leaks? Any way I could somehow stuff my old embarrassing beliefs and expressions and sentiments back into the corporeal box? Any way in which I could regain my rationalist composure?

“Well,” said Janet, “you could make a start by paying attention to your current demeanour. Try to look a little more in control. A little more adult. Sit up straight and wipe the chocolate from around your mouth. And try to look at me when you’re talking rather than at that thing in your lap.”

“That’s not a thing,” I said. “That’s my friend. My companion. My confidante. That’s Teddy.”

“Of course it is,” said Janet, reaching for the bill. “Of course it is.”