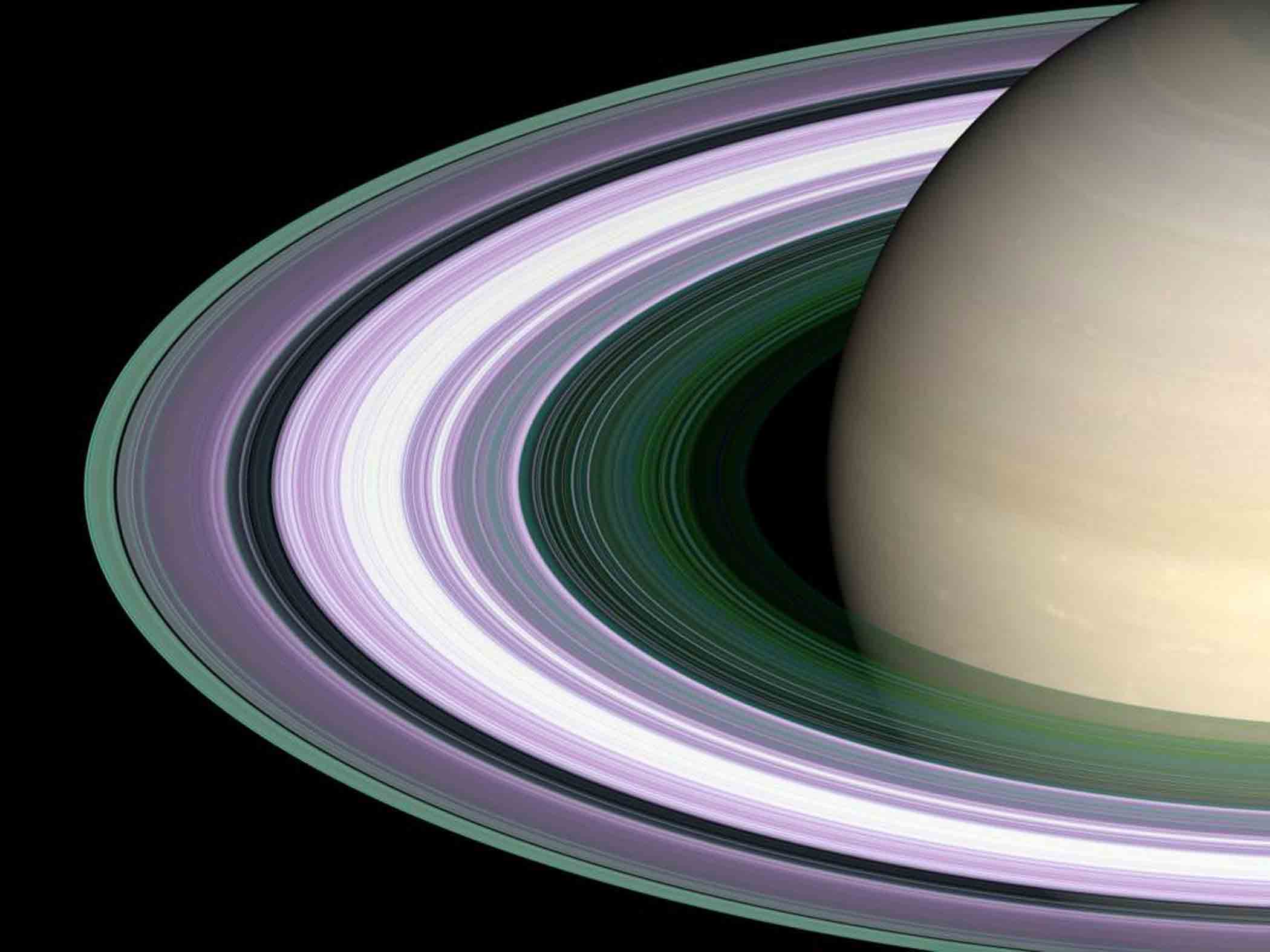

Galileo was a giant in the history of science, famous for discovering that a swinging pendulum keeps perfect time and that all bodies fall at the same rate. But arguably a low point in his career was when, in 1610, he pointed his new-fangled telescope at Saturn and claimed it was a planet … with ears.

He changed his mind the next year and said the planet had a big moon on either side. But the following year they had vanished. Galileo died baffled. The mystery was only solved, 50 years later, when Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens used a bigger telescope and recognised, correctly, that Saturn is girdled by a system of rings. As they change their orientation, they can appear edge-on – vanishing from view – or at an angle to the line of sight – when they do indeed look like ears.

In 1980 and 1981, NASA’s Voyager 1 and 2 space probes revealed tens of thousands of narrow ringlets. Made predominantly of ice chunks, ranging in size from a dust grain to an office block, the rings are the relic of a disintegrated object, perhaps a moon. They are so extensive that, if around the Earth, they would stretch more than a third of the way to the Moon.

Oh, and one last thing. Saturn’s rings aren’t, actually, er, rings. They are spirals – like the grooves on an old vinyl record. In fact, the same process that creates them – so-called spiral density waves rippling out through the orbiting ice particles – creates the spirals of spiral galaxies like our own Milky Way.

Rings – or spirals – are not uncommon: four of the eight planets in the Solar System possess them, though none are as spectacular as Saturn’s. In fact, the Earth, shortly after its birth 4.55 billion years ago, was girdled by rings, the ejecta of a titanic collision with a body the mass of Mars. After a while, the ring material congealed into … the Moon.

Marcus Chown’s latest books are Tweeting the Universe and Solar System, both published by Faber