There are currently around 125 million women alive in the world who have undergone some form of female genital mutilation (FGM), a procedure in which female genitalia are altered or injured for non-medical reasons. The dangers include severe bleeding, problems urinating, infections, and infertility – not to mention excruciating pain during intercourse and childbirth.

The practice is most prevalent in parts of Africa – countries such as Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti, and Egypt – where it is deeply rooted and takes place across ethnic, religious, and class divides.

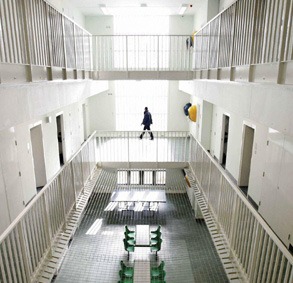

Given the scale of the problem, it is perhaps surprising that it has taken until 2014 for the first hospital dedicated to treating the victims of FGM to be built. Construction of the hospital, located in Burkina Faso – one of Africa’s poorest nations – has now been completed. Women from all over the country and even elsewhere in the continent (Mali, Senegal, Kenya) are traveling to the town of Bobo-Dioulasso for surgery. Yet the hospital stands empty: the government will not allow it to open because of licensing issues.

In a report for the BBC’s Newsnight programme, journalist Sue Lloyd-Roberts spoke to women from Burkina Faso who had signed up for surgery, which was to be offered free of charge by two American doctors who specialise in gender reassignment. The plan was that they would carry out as many procedures as possible, while training local doctors to continue the work. The surprisingly simple surgery can be done under local anesthetic and takes about 45 minutes. While the visible part of the clitoris is removed during FGM, the majority remains below the surface and can be pulled up. This means that the procedure not only reverses the physical damage of FGM, but also restores the ability to feel sexual pleasure.

The hospital – known to its sponsors as the Pleasure Hospital – has been under construction since 2011. Hundreds of women have signed up for procedures, and the first lady of Burkina Faso was due to open it.

So why has the government insisted its doors remain closed? The health ministry has said that the US non-profit that built the hospital failed to provide essential documents; Clitoraid, based in Las Vegas, insists that this is not true.

The situation is complicated by the origins of Clitoraid, which was established by a strange religious sect, the Raelians, who believe in UFOs and hold that the purpose of life is the pursuit of pleasure. Around a decade ago, wealthy Raelians based in California and Canada launched Clitoraid, invited donors to “sponsor a clitoris” by donating, and ultimately raised £250,000 to build the hospital.

Despite originally citing a licensing dispute, the health ministry then told another journalist that “medical organisations should be focused on saving lives and not advertising their religion in an attempt to convert vulnerable people.” The Raelian movement released a statement accusing the government of Burkina Faso of bowing to pressure from the Catholic Church. The sect has clashed with the Catholic establishment before over issues including condoms. The Catholic Church in Burkina Faso has dismissed the Raelians’ accusation as a “poisonous rumour”.

Whatever the truth behind the different forces opposing the hospital, this certainly goes beyond the tension between a peculiar sect and the religious establishment. The resistance to the Pleasure Hospital points to a wider intransigence about the position of women, and a squeamishness about focusing on female pleasure – neither of which are unique to Burkina Faso. It is that same intransigence that fortifies regressive practices like FGM in countries across the world. Before their licenses were revoked, the doctors managed to carry out several procedures. As the dispute rolls on, the hundreds of other women hoping to be treated can only keep waiting and hoping.