This article is a preview from the Autumn 2014 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

“Bliss was it in that dawn to be a paranoid crackpot,” Wordsworth might well have written of the summer of 2014, “but to be a full-fledged conspirazoid dingbat was very heaven.” The downing of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine on 17 July was a cavalcade of Christmases for the tinfoil-titfered legions who insist upon believing that our lives are minutely orchestrated by malign and hidden forces who toy with us to a soundtrack of their own triumphant cackling, perhaps gently underpinned by the stroking of cat fur.

It was an air disaster that befell an airline which had recently suffered probably the weirdest air disaster of all time, over disputed territory, brought about by possibly Moscow-backed perpetrators. MH17 demonstrated, like 9/11 before it, that, in the modern, online world more than ever, conspiracy theories have become to public discourse what Japanese knotweed has to unlucky gardeners – a robust, self-replenishing pest that defies the most vigorous efforts to keep it down, and is capable of quickly overrunning an entire plot.

Where MH17 was concerned, there was a straightforward, if undoubtedly horrifying, explanation – that the bumpkin army of the Donetsk People’s Republic, equipped by Russia with weapons rather more sophisticated than themselves, had failed to distinguish between an Antonov AN-26 belonging to the Ukrainian Air Force and a Boeing 777 belonging to Malaysia Airlines, and had accidentally murdered 298 entirely blameless people. This did not stop a number of people, for a variety of reasons, seeking/inventing alternative scenarios.

The leaders of Ukraine’s separatist rebellion were understandably keen to distance themselves from the crime, and swiftly blamed their opponents, arguing that Kiev had whacked MH17 to make them look bad; Izvestia reported this immediately after the crash, launching an episode that was shabby and mendacious even by the standards of Russian media. A few days later, Komsomolskaya Pravda elaborated, suggesting that MH17 had been tracked by a US satellite and shot down by a Ukrainian SU-25 (it was subsequently revealed that the SU-25’s Wikipedia page was fiddled by Russian interlopers in order to lend it the necessary capabilities). Russia’s absurd state-backed news channel RT floated the theory that not only had Ukraine shot down MH17, they’d done it in the belief that it was Vladimir Putin’s presidential jet, which does indeed bear a not dissimilar shape and livery (except, as RT’s report buried a few paragraphs below the headline, that Putin’s aircraft hadn’t flown over Ukraine for months). A few outlets, splendidly, linked MH17 to the still lost MH370, reasoning that the doomed plane was in fact the same one which disappeared in March, now filled by its CIA hijackers with pre-killed corpses and remotely flown to, and blown up over, its final destination.

The logic behind the construction and propagation of the above is not difficult to distil. We have all told preposterous whoppers when seeking to absolve ourselves of blame, generally for much smaller misdemeanours.

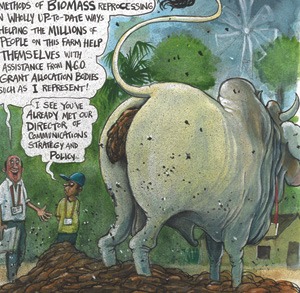

What is rather more perplexing is the energy – even the weird, grim glee – some apply to believing them. It’s certainly true that governments lie, and that media outlets are partial. It is far more often true that people, good and bad, acting under pressure and with incomplete information, bugger things up. Jon Ronson’s terrific study of conspiracy fans, Them, was framed as a quest to find “the room”. By that he meant the room, almost certainly smoke-filled, in which some insist that our overlords, almost certainly extraterrestrial and reptilian, plan our destiny and/or doom. But there isn’t a room. There are many, many rooms. And any study of history – or any off-the-record conversation with anyone who has participated in such a conclave at a time of crisis – will confirm that these rooms are populated by nervous, uncertain people, many of whom will be holding throbbing heads in sweaty hands, muttering things to the effect of “What the hell do we do now?”

The widespread determination to believe otherwise is perhaps especially bewildering and tiresome to those of us of the infidel persuasion. Because belief in conspiracies surely comes from the same place as belief in gods – the human need to reassure ourselves that the world is ordered, that things happen for a reason, that someone, somewhere is actually in charge, and that surely 298 people can’t die just because some hillbilly militiaman takes a swig of turnip vodka and asks, “What does this button do?”