This article is a preview from the Winter 2014 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

Cuckoos are irresponsible birds by human standards; they lay their eggs in other birds’ nests, and the young cuckoos, when they emerge from the egg, shove their foster brothers and sisters over the edge with no conscience at all, and swallow every worm that the responsible foster mother brings. They don’t set us a good example at all. Of course, there isn’t a moral dimension here, really: the cuckoo does it because that’s the sort of bird she is. And the bird that made the nest doesn’t feed the new chick because she’s overflowing with compassion: she can’t help what she does. That’s the sort of bird she is.

But whether or not it’s the business of nature to provide us with moral examples, human beings have been taking moral examples from nature for thousands of years. We can take moral lessons from anything: that’s the sort of birds we are. As it says in the Book of Proverbs: “Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise.” How many times have I quoted that to my teenage sons, urging them to get up in the morning?

I’ll return to the cuckoo later, but first I want to discuss responsibility. We are all responsible in various ways as social beings, as citizens, as fellow members of the human race, and I don’t suppose we’d disagree about what sort of things those responsibilities cover. We should look after those who depend on us. We should be as truthful and honest as we can manage. We should bear in mind the general good, and act in a way that promotes it rather than damages it. And so on. We’d probably agree about 90 per cent of things like that whether we were religious or not, whether we were humanist or Christian or Jewish or Muslim or Hindu or Buddhist. (Those people who maintain that you can’t be moral unless you have faith in a religion are talking nonsense, of course.)

So our general responsibility as human beings is pretty easy to understand – as I say, we would all probably agree about most of it. But I’m a writer, and writing books is the only thing about which I can claim any specialist knowledge. It’s the only reason people phone me and ask me to do things. I know how to make up the sort of things you get paid for, and I’m lucky enough to live in a country where most writers are fairly safe from being sent to prison. Plenty of other writers in other places are not that lucky.

There is a special responsibility, over and above being a good citizen, that comes with being a writer of the sort I am. I take it for granted that the writer is not a special sort of person, or a superior sort of citizen. All the normal responsibilities of the citizen are mine too. The extra responsibilities are those that come not from being anything special but from doing something in particular.

I think we writers have a responsibility towards our fellow writers. It’s a good thing to speak up for our colleagues who are mistreated or unjustly imprisoned, or to take joint action against injustice or oppression of any sort, whether it’s political in origin, or religious, or commercial, as these days it might well be. But more important even than that, there are writers who are under threat from regimes that disapprove of free speech, writers who risk not just their bank accounts but their freedom and sometimes their very lives. We who don’t live in such danger can only salute and admire the writers who work under such conditions, and support them as well as we can, and be inspired by their example.

Then there’s a responsibility towards the place that our craft or sullen art, as the poet Dylan Thomas called it, has in society. What is the value of art to the society in which it is produced? Is it important in any sense other than the financial? We’re used to hearing about the financial case, used to hearing people say things such as “The arts are important because they bring in so many billion pounds a year to our economy.” That’s true enough, but we ought to be able to say that the arts have other values as well that can’t be measured in financial terms. The arts in general, but here I mean especially literature, stories, poems and drama, and books of travel and history and biography, and books about science and philosophy and, yes, books about religion too – they do what isn’t done by any other human activity, and make explicit, in language that is beautiful and memorable, what it is to be human. There is a social, moral, political value in that, and we ought to say so clearly. The politicians won’t say it unless we give them the words and the arguments. So we must do that.

Then there’s education. We writers ought to make it clear too that the arts – not just learning about them, but doing them, actually writing and painting and playing music – have a vital part to play in the lives of our children. They have to do with enlarging and clarifying experience, in opening new worlds of possibility and delight and understanding and emotion. We who tell stories should be ready to say so. We should speak up when funds are being cut – funds for all kinds of art, for children’s theatre, for teaching music and lending musical instruments, for allowing students time to learn from writers and poets. All those good things are under threat, because the people in charge of the money can’t see any immediate financial advantage from spending it like that.

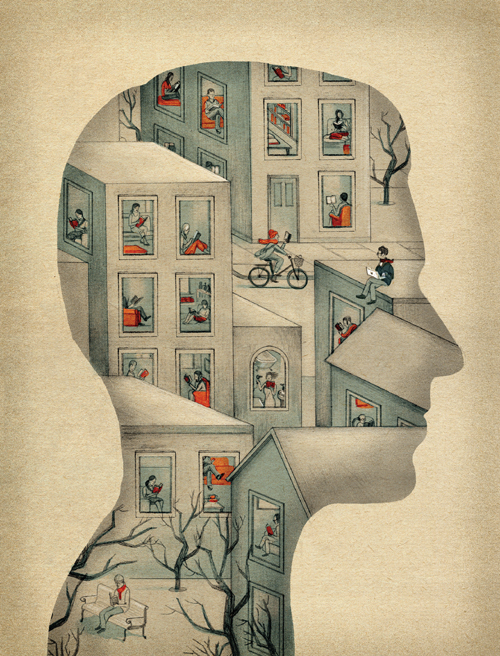

So we have to remind them that education is a long-term business. Sometimes years will go by before the noisy boy at the back of the class, the sullen girl who never speaks, will find that particular poem, that one story, that they heard on that dull afternoon in November when they were 13 years old, suddenly speaking to them. All this time the seed that was planted in their mind has been quietly resting, and gathering its strength, and getting ready to germinate when the right conditions arrive, and then they do arrive, and it grows and emerges and bursts into flower as they remember the words of the poem or the drama of the story, and at last they have a way of understanding the relationship they’re in, the job they do, their predicament as a human being in a world they didn’t make. Suddenly they have a template, and words to make their feelings and thoughts clear to themselves. That is one purpose of the arts in education. We know it, and we should say so.

Now what about the writer’s responsibility towards the audience? Towards the readers? Do we have any responsibility towards them? Publishers would say yes, of course we should consider the audience, of course we should do our work to suit what the market wants. So that’s what publishers want us to write, and that’s what they try to publish. But my own feeling is that what I write is none of the readers’ business. Their place is to buy or borrow, and read, and then, if they like what they read, buy my next book. That’s their job. I don’t want their advice about what to write or their thoughts about my work in progress or their suggestions about what should happen next.

But once the book is published, the whole political aspect changes. Writing is despotism, but reading is democracy. Once the reader opens the book, they enter a space as private and secret as the polling booth. If there is a soldier with a rifle watching how you fill in your ballot, that’s not democracy; democracy is when no one knows how you voted. So it is with reading. The private space between the book and the reader is something utterly precious and individual. The conversation a reader has with a book is none of the writer’s business, unless the reader chooses to tell them about it. I profoundly disagree with those writers who insist that there is a right way to read their books and a wrong way. “No, you’ve got it completely wrong; you haven’t understood a bit of it; it doesn’t mean that at all, it means this.” Some writers are like that. But I think it’s none of the reader’s business how I write, and it’s none of my business how they read. They might read better than I can write. They might see things I was unaware of as I wrote them down. To limit a reader’s permitted response to what the writer himself or herself knows about their own work is an infringement of freedom. Reading should be free.

But just because the writer is a dictator, a tyrant, a despot, it doesn’t mean that they’re completely free. It just means that they’re in charge, and that’s the next responsibility I want to look at. Taking the work seriously, that’s the point. If we embark on a task that’ll take years to finish and involve every part of our imagination and our memory and our intellect and our stamina, then we should not approach it as if it were trivial. Actually, I don’t think we could. A long task, like writing a novel, has got to be something we take seriously, and when we do that, we’ll find our moral nature involved whether we intend it to be or not. We can’t help it.

This leads to another question. Should the writer be engagé? Should he or she be committed to some political or social or religious cause in a way that colours the way they work? Should we write in order to express or embody our conviction about this or that political position? Should a humanist writer, for example, consciously promote humanist values and ideas in the course of writing a work of fiction? Or should literary art, should art in general, be created simply for the sake of the art itself?

“Art for art’s sake” was an idea that was given its clearest and most uncompromising expression in Oscar Wilde’s preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray. He said, “There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all.” But if we read that story, we’ll find it saying something rather different. Wicked behaviour, says the story, corrupts and ruins us. Acts that have a moral dimension have moral consequences.

In fact I think Wilde was in the position I described a moment ago: faced with a lengthy and complicated task, he couldn’t be frivolous about it – he had to take it seriously to do it at all, and that meant engaging with every aspect of his own nature, including the moral and ethical principles he held most deeply, even if he pretended to deny them.

But to come back to the engagé question: should the writer consciously try to promote not just political, but party political, not just religious but specifically doctrinal views in the books he or she writes? Should we start with a cause and then write a story to fit it?

The answer in my case would be simply that I couldn’t do it. When I write a story there are many things I need not to know. I need to feel myself moving into a great fog-bank of uncertainty just as evening is falling and the light’s beginning to fade. If I knew what I thought and felt about the characters and the events I was going to describe, I wouldn’t want to start the journey, because a good part of the pleasure and satisfaction of writing is finding out those things as I go along and adjusting everything to the discoveries I make en route. When I was younger I did try to write stories that embodied various opinions or convictions of my own, and they lay dead on the page and didn’t move. It was like trying to blow up a punctured tyre. No success at all. So whether or not it’s something I feel I ought to do, I can’t do it, and I’m not going to try any more. Working like that is a brutal kind of toil, slave’s work, as John Ruskin called it, unredeemed, unrewarded by any delight. And we must have delight.

Part of the delight of writing consists of the engagement with the medium we use, with language. And I want to say a little about our responsibility towards that wonderful, endlessly rich, living thing that language is. Once we become conscious of the way language works, and our relationship to it, we can’t pretend to be innocent about it; it’s not just something that happens to us, and over which we have no influence. If human beings can affect the climate, we can certainly affect the language, and those who use it professionally are responsible for looking after it. I mean the sort of taking-care-of-the-tools that any good craftsman tries to teach an apprentice – keeping the blades sharp, oiling the bearings, cleaning the filters.

For example, those of us who use language to tell stories should continually make sure of the meaning of the words we want to use by looking them up in a good dictionary; in fact we should have several dictionaries, old ones and new ones. Words change, they have a history as well as a contemporary meaning; it’s worth knowing those things. There’s a pleasure in discharging this responsibility – of sensing that we’re not sure of a particular point of grammar, for example, and in looking it up, and getting it to work properly. And even if we’re the only people who ever notice, that’s fine; if readers don’t know what the wrong form is, they won’t mind if we get it right. It seems worth the effort to me, besides being more interesting.

Next in my list of responsibilities, but close to the one about language, is one about the craft itself. We should take a pride in getting things to work well. If we’re telling a mystery story, we shouldn’t cheat by letting the hero have information that we withhold from the reader. If we’re writing a film script set in the past, let’s make sure that the dialogue is at least as authentic as the costumes. Look at how other writers have worked. Don’t let’s think we’ve got nothing in common with Anthony Trollope just because he’s a dead white male. If his books are still being read, there’s a reason for that; let’s read him and find out what’s made them last. He was a storyteller just as we are. What can we learn from him?

Actually, that last responsibility is one I feel strongly about: writers should read. I once met a young poet who had no interest in what he called old-fashioned poems, with their thees and thous and fancy words that no one could understand. He only liked poems from the present, especially funny ones that anyone could understand at once. I asked if he knew any poetry by heart, and he looked at me as if I was mad. Why would he bother with that?

Well, it seemed to me that that young man had probably not been lucky enough to come across poetry before he knew he was prejudiced against it. I’d been lucky in that way: there were books of poetry in the house when I was a child, I was curious, I read poems without fully understanding them, but conscious that there was some kind of magic going on. That’s the only way I can put it that remains true to the feeling I had then and the experience I have now when I encounter great poetry: there is a sort of enchantment about it, it does work a spell. It has something to do with the sound and the music of the words, of course, which is why it always works best when you read it with your mouth as well as your eyes. I’m quite happy to use words like magic, enchantment, spells, even in front of humanists, who probably don’t believe in that sort of thing. That’s the best way I can find to describe the experience, and we have to be true to what we know.

I mentioned Dylan Thomas earlier; it’s his centenary this year. Like many other writers, he suffered a decline in his reputation after his death, which came in 1953 when he was 39; his poetry was felt by some critics to be excessively self-indulgent and not intellectually rigorous. But he had a huge influence on me when I was a teenager finding out for myself what poetry was and how it worked. Living in Wales, it was natural to read Dylan Thomas, and I’m very glad I did.

But I read a great deal of poetry besides Dylan Thomas. I read Shelley (“O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being,/ Thou from whose unseen presence the leaves dead/ Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing”) and William Blake (“Tyger, tyger, burning bright,/ In the forests of the night”) and John Keats, describing the song of the nightingale (“The same that oft-times hath/ Charm’d magic casements, opening on the foam/ Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn”) and Coleridge and Wordsworth and dozens of others, both ancient and modern. Very romantic, you see. I was a romantic extremist. No point in being a romantic moderate at the age of 16 – no point in being a moderate of any sort.

So I plunged into poetry like someone falling in love, who can’t get enough of the object of his passion, who’s intoxicated, obsessed or, as one might say, bewitched. And I was lucky, because I met these great poems on my terms and on theirs, but very seldom on anyone else’s. I didn’t do them at school. I didn’t have to analyse them and explain how they achieved their effects or paraphrase them or translate them into prose. My encounters with them were private, secret, democratic. A year or two later I encountered Milton’s Paradise Lost, but that was lucky too: I did so under the guidance of a wise teacher who let us listen and read aloud before we had to explain.

I want to stress the importance of serendipity here: the faculty of making happy chance discoveries. I was lucky enough to find poetry lying around, so to speak, and I picked it up and explored it for myself while the rest of my family couldn’t care less about it. It’s profoundly important for teachers and parents to leave things lying around without pestering the child for a response to them. Fill the background with wonderful things – music, paintings, stories, books about science – and then get out of the way and say nothing. But we can’t do that in schools these days; every encounter has to be planned in advance, and have a measurable outcome, and fit into a prescribed scheme of work. So it probably shouldn’t have surprised me that the young poet I spoke to had never had the chance to meet poetry as I did, and experience the magic at first hand, or feel it communicate before it was understood, in the phrase of TS Eliot’s.

But I was lucky, and by doing that I learned where my own imagination was at home. I learned that I’m perfectly at home in a state of doubt and uncertainty: that’s the state I enter when I write. I know how to see things in the twilight. I’m at ease with ghosts and witchcraft and magic – with fantasy, in a word. I understand those things, I’m at home where they are, I can work freely there, and every part of my nature is satisfied by the task.

I’ve learned how to recognise a story idea when it comes to me. It doesn’t come as a theme or a cause, as I said a few minutes ago; what happens instead is that a picture comes into my mind. It might be a young girl going into a room where she’s not supposed to be, and looking around, and then she hears someone coming and she has to hide. Or it might be a young boy, exhausted and frightened, on the run from the authorities, who comes across a window into another world. Or a doctor examining a dead body, and finding that its heart has been replaced by a piece of clockwork.

Something completely unexpected and full of possibility suddenly falls into my mind, and is so intriguing that I have to put everything else down and attend to its demands. So here am I in the position of the bird and the nest in which a cuckoo has laid her egg. The cuckoo didn’t come to me on purpose: any old nest would have done. That’s the sort of bird she is. And I, dutifully attending to my other chicks, start feeding the great new baby when it emerges. I don’t do it because I feel I ought to: I can’t help it. That’s the sort of bird I am. I’m so intrigued by all the implications of this egg, this chick, this shiny new story idea, that all I want to do is nurture it and see what it’ll grow into. And if it throws my other babies over the side, well, I can always make more of those.

Now I come back to the subject I began with, which was responsibility. For me, the most important responsibility is to serve the story, to serve my imagination, and not expect the story or my imagination to serve me, or my principles, or my opinions. This is the point where responsibility takes the form of service, freely and fairly entered into. When I say I am the servant of the story, I say it with pride. I honour the contract between us.

And as the servant, I have to do what a good servant should. I have to be ready to attend to my work at regular hours. I have to anticipate or guess where the story wants to go, and find out what can make the progress easier – by doing research, that is to say: by spending time in libraries, by going to talk to people, by finding things out. I have to keep myself sober in working hours; I have to stay in good health. I have to avoid taking on too many other engagements: no man can serve two masters. I have to keep the story’s counsel: there are secrets between us, and it would be a gross breach of confidence to give them away.

And I have to be prepared for a certain wilfulness and eccentricity in my employer – all the classic master-and-servant stories, after all, depict the master as the crazy one who’s blown here and there by the winds of impulse or passion, and the servant as the matter-of-fact anchor of common sense; and I wouldn’t want to change a pattern as successful as that. So, as I say, I have to expect a degree of craziness in the story.

“No, master! Those are windmills, not giants!”

“Windmills? Nonsense – they’re giants, I tell you! But don’t worry – I’ll deal with them.”

“As you say, master – giants they are, by all means.”

No matter how foolish it seems, the story – the imagination – knows best. And finally, as the faithful servant, I have to know when to let the story out of my hands; but I have to be very careful about the other hands I put it into. Our last and most responsible act as the servant of the story is to know when we can do no more, and when it’s time to admit that someone else’s eyes might see it more clearly. To become so grand that you refuse to let your work be edited – and we can all think of a few writers who got to that point – is to be a bad servant, not a good one.

A wonderful mental freedom opens out in front of us when we discover what really enthrals us. The young boy or girl hearing the music that they’ll love for the rest of their lives – hearing it for the first time, whether it’s Bach or Beethoven or Chuck Berry or Miles Davis – what they feel at that moment is a sudden increase in freedom, a sudden widening of the horizons of possibility. Or the child suddenly intoxicated by catching sight of a painting which to the rest of us is familiar, we’ve seen it a hundred times, it no longer moves us – Van Gogh’s starry sky, for example – seeing it for the first time, and being thunderstruck. Or discovering with increasing excitement the worlds of biology, or architecture, or engineering, or mathematics, or becoming a passionate lover of poetry, as I did. It’s like suddenly becoming free, discovering a wide new world in which you are a native, a citizen, and you never knew it until now.

William Blake, the poet who was also a painter, whose work was one of those worlds into which I learned to find the door, was one of the great poets of freedom. He wrote of the “mind-forg’d manacles” that all of us have to escape: the habits of thought and activity that keep us imprisoned in old, narrow, stale and sterile ways of understanding and feeling. The world is always bigger than the mind-forg’d manacles allow us to know.

Those of us who can remember the moment, usually in our adolescence, when the door opened into a new world, a world in which we were citizens and we’d never realised it – those of us who are writers, painters, musicians, scientists, teachers, workers in any field that depends on the free exercise of the whole mind, including the imagination – don’t let’s forget the children, and the importance of leaving things lying around and not pestering the children for a response. Any of those valuable things might turn out to be a cuckoo, and any of those children a nest.

This essay is adapted from a talk Pullman gave at the 2014 World Humanist Congress, courtesy of the British Humanist Association.