This article is a preview from the Spring 2016 edition of New Humanist. You can find out more and subscribe here.

I greatly miss the arguments I used to have with true believers. There were always two clear-cut sides: two sets of loudly declared and utterly incompatible positions. You either believed in God or thought the whole idea absurd. And it was as ridiculous not to know exactly where you stood on God as to express ambivalence about your support for Spurs.

But nowadays if religion comes into the conversation nobody admits to any sort of certainty. Unless you’ve been fortunate enough to secure the company of Richard Dawkins for the evening, you will routinely find yourself surrounded by a motley collection of equivocators. Only last week an old friend told me that although he was an atheist he very much disliked “militant atheists” who felt the need to convert others to their point of view. Would he, I wondered, be quite so ready to turn the other conversational cheek, if he kept running across people who believed the moon was made of Marmite?

It’s all a million miles from the time when I could readily outrage my pious fellow Catholic students at St Mary’s College in Liverpool by offering to stand in the middle of the road and shout: “If there really is a God then I dare him to strike me down dead.” Many of my schoolfriends couldn’t even look while I went through my paces in case they were blinded by the stroke of lightning that was sure to follow such public blasphemy.

But I can never reflect upon such contrasting certainties without remembering the quite extraordinary moment back in the ’60s when the minister in charge of Tooting Bec Methodist Church asked me a theological question of such directness that there was simply no room for equivocation.

“Would you believe in God,” he asked, “if at this very moment Jesus were to walk through that door?”

Unless I came up with a sufficiently positive response, I knew there was every chance that he would there and then refuse to allow my intended and myself to marry in his church. This wasn’t a situation of my own making. I’d only reluctantly agreed to a church wedding as a sop to my beloved’s mother, who’d become so anguished at discovering her daughter’s pregnancy that only the promise of a marriage in the sight of God had been sufficient to dampen her hysteria.

I had drawn the line at a Catholic wedding. Having spent the first fifteen years of my life trying to keep priests away from my private parts, I had no wish to have anything more to do with Rome and its servants. Methodism had seemed a promising alternative. Of course some radical historians had indicted John Wesley and his followers for undermining the 19th-century workers’ revolution with their talk of the pie soon to be available in the sky, but at least Methodists had shown commendable courage in their support for CND and nuclear disarmament.

Despite such apparent liberality, the Methodist minister we’d gone to see in Tooting had proved surprisingly obdurate about the Supreme Being. Did I believe in God? he’d asked almost as soon as I’d outlined our reasons for choosing a Methodist wedding. “Not really,” I confessed.

“You don’t feel that you were put on earth to serve some higher purpose?”

“Not really.”

It must have been the increasingly anguished look on my future bride’s face that had then led him to give me one last chance of redemption with his story of Jesus popping his head around the presbytery door.

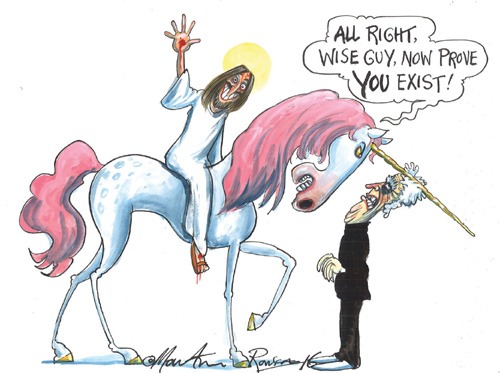

“Please, Laurence,” said my betrothed wearily. “If Jesus really did come through that door now you’d have to admit he existed. And you can’t be a proper materialist if you deny the evidence of your own senses.” I swallowed hard and made one last attempt to save the day. “Right,” I said, “I’m just about prepared to admit the existence of Jesus if Jesus does indeed come through that door. But on one condition. He must be seated on a unicorn.”

There was silence. My intended grimaced. The minister leaned slowly towards me.

“I think we can live with that,” he said. “Now, would you like piano or organ for the ceremony? We’d prefer you to choose piano because at the moment we don’t have an organ.”

We agreed without any further debate to settle for the piano.